UPSC Foundation

2026 Prime Batch

1-Year integrated Prelims + Mains + Interview preparation program

Stay Updated

Daily Practice & Updates

With reference to cybersecurity risks in space systems, consider the following threats: 1. Signal jamming 2. Spoofing of satellite signals 3. Unauthorized command uplink to satellites 4. Solar radiation–induced hardware malfunction

Our Programs

Explore Our Courses

Comprehensive preparation programs for UPSC, JPSC, BPSC & State PCS examinations with expert faculty and proven results

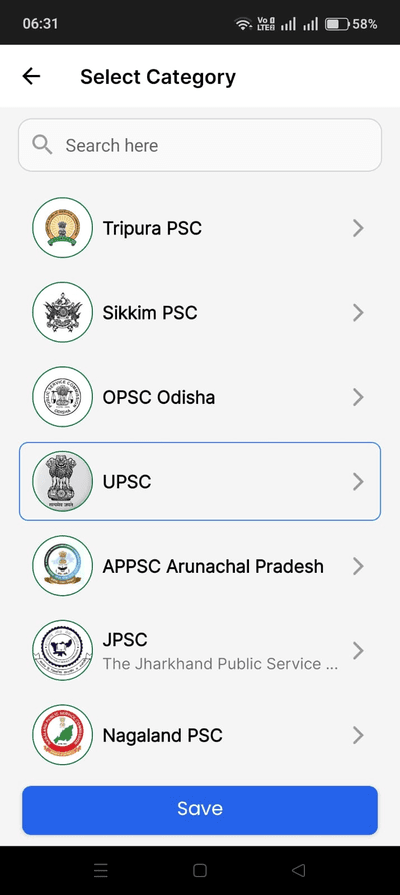

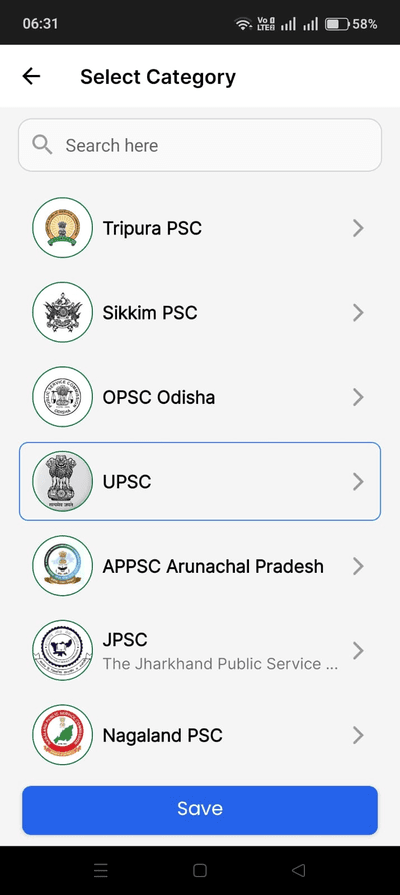

| S.No. | Course / Program | Category | Action |

|---|---|---|---|

| 01 | UPSC Civil Services Exam | UPSC | View Details |

| 02 | BPSC Courses (Bihar PCS exams) | State PCS | View Details |

| 03 | MPSC Meghalaya Civil Services | State PCS | View Details |

| 04 | Nagaland PSC | State PCS | View Details |

| 05 | Tripura PSC | State PCS | View Details |

| 06 | Sikkim Civil Services | State PCS | View Details |

| 07 | OPSC | State PCS | View Details |

| 08 | APPSC Arunachal | State PCS | View Details |

| 09 | JPSC Courses (Jharkhand State PCS) | State PCS | View Details |

| 10 | JKPSC Courses (Jammu and Kashmir Exams ) | State PCS | View Details |

| 11 | MPPSC Courses (Madhya Pradesh State Exams ) | State PCS | View Details |

| 12 | APSC Exam (Assam Public Service Commission) | State PCS | View Details |

| 13 | RAS Course (Rajasthan Administrative Service Exam) | State PCS | View Details |

| 14 | UPPCS Course (Uttar Pradesh Civil Services Exam) | State PCS | View Details |

UPSC Civil Services Exam

UPSCBPSC Courses (Bihar PCS exams)

State PCSMPSC Meghalaya Civil Services

State PCSNagaland PSC

State PCSTripura PSC

State PCSSikkim Civil Services

State PCSOPSC

State PCSAPPSC Arunachal

State PCSJPSC Courses (Jharkhand State PCS)

State PCSJKPSC Courses (Jammu and Kashmir Exams )

State PCSMPPSC Courses (Madhya Pradesh State Exams )

State PCSAPSC Exam (Assam Public Service Commission)

State PCSRAS Course (Rajasthan Administrative Service Exam)

State PCSUPPCS Course (Uttar Pradesh Civil Services Exam)

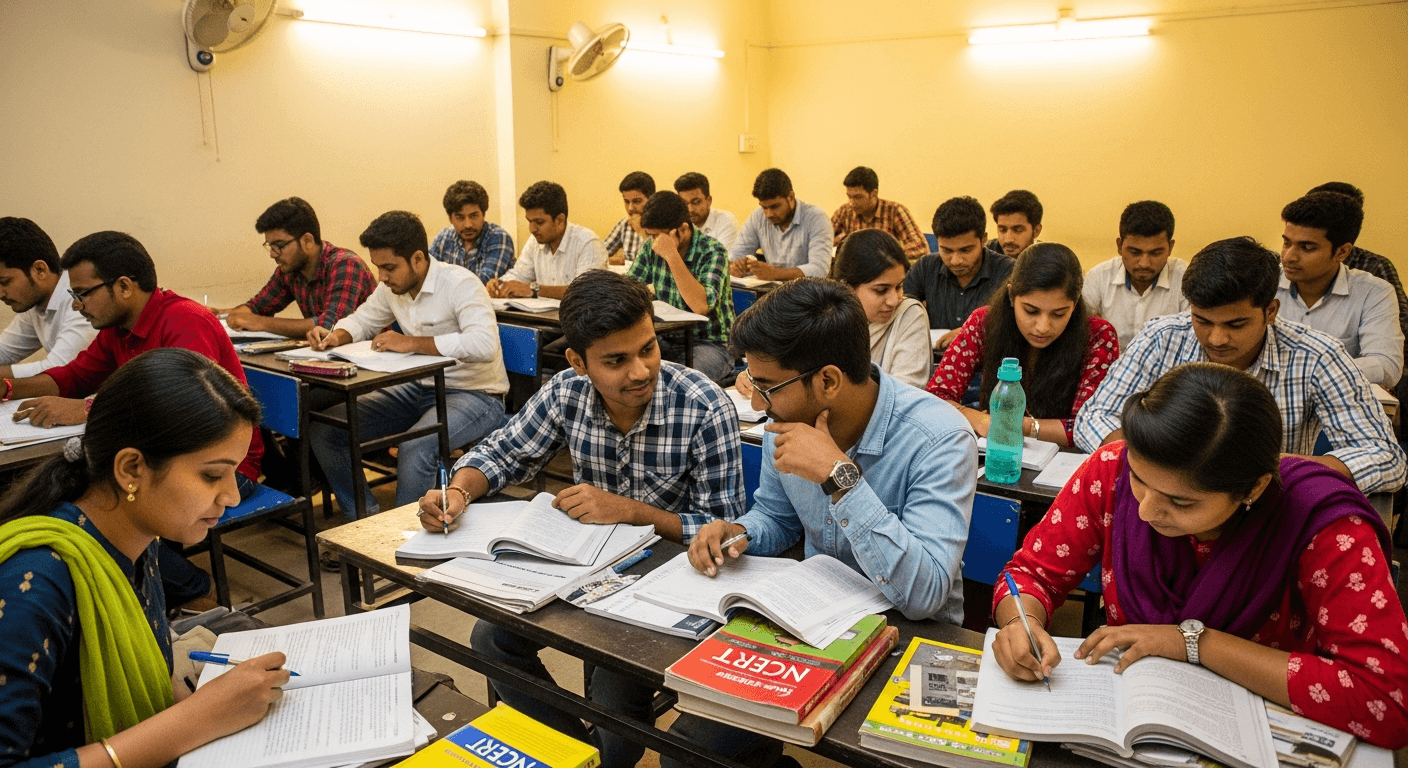

State PCSUPSC Coaching in India — Built for Serious Aspirants

Since 2015, LearnPro has evolved into a structured preparation platform for UPSC and State PCS aspirants, built on the idea that serious examinations demand serious intellectual training.

Academic Philosophy

LearnPro is built on three core principles:

Conceptual Clarity Over Information Overload

Civil Services preparation is not about collecting notes; it is about understanding interconnections between polity, economy, society, and technology.

Institutional Understanding

Students are trained to understand how constitutional bodies, regulatory institutions, fiscal systems, and public policy mechanisms function in practice.

Examination-Linked Depth

Every course is aligned with the demands of Prelims, Mains, and Interview — not in isolation, but as an integrated framework.

The focus remains on analytical thinking, structured answer writing, and policy-oriented reasoning.

Experience & Institutional Exposure

Why LearnPro is Best UPSC Coaching in India

LearnPro provides a disciplined teaching approach which aligns with the latest trend of UPSC civil services exam. All our courses are customized to address the precise demands of the exam, ensuring aspirants gain relevant knowledge and skills essential for their success.

We regularly update our content to meet dynamic exam requirements with advanced courses like GS Foundation, CSAT, Prelims Test Series, Mains Answer Writing, Current Affairs, and Live-Online programmes.

Our dedicated and highly professional team undertakes rigorous research and continuous development to provide qualitative, well-researched study material and innovative teaching methodologies catering to the diverse learning needs of aspirants.

Our dynamic approach is suitable for every aspirant which provides them a distinct roadmap, expert support, and quality resources to build a strong foundation tailored to different preparation learning preferences.

LearnPro provides the following courses for UPSC & State PCS preparation:

- GS Foundation Course: An intensive one-year course focusing on the entire General Studies Prelims and Mains syllabus.

- Live/Online Course for UPSC CSE: A comprehensive integrated program combining NCERT and GS Foundation for gradual syllabus coverage.

- UPSC Prelims Revision Crash Course: A focused revision course with advance mentorship and strategic guidance for working professionals.

- Mains Test Series for UPSC CSE: Structured test series with detailed evaluation and feedback to sharpen answer writing skills.

What Our Students Say About Us

Honest feedback from UPSC and State PCS aspirants preparing with LearnPro

“The study materials and mock tests at LearnPro are very well-structured. The conceptual clarity I gained here helped me understand complex topics like Indian Polity and Economy in a way textbooks never could.”

Vikash Kumar

UPSC Aspirant

“The JPSC-specific course was tailored perfectly for the exam pattern. The bilingual content in Hindi and English made it much easier to revise and retain key concepts.”

Anjali Mishra

JPSC Aspirant

“LearnPro's current affairs coverage is outstanding. The daily updates and editorial analysis save hours of newspaper reading and give me exam-ready material every day.”

Rohit Prasad

BPSC Aspirant

“Best platform for PCS preparation. The bilingual content was a huge advantage for me. The answer writing practice with structured feedback improved my Mains approach significantly.”

Sneha Gupta

State PCS Aspirant

“The Mains answer writing programme changed my approach completely. The structured framework they teach for writing analytical answers is something I haven't found anywhere else.”

Amit Ranjan

UPSC Aspirant

“LearnPro helped me build a strong foundation for UPSC. The study materials and mock tests were exceptional. The faculty guidance on optional subject strategy was very helpful.”

Priya Kumari

UPSC Aspirant

Got Questions?

Frequently Asked Questions

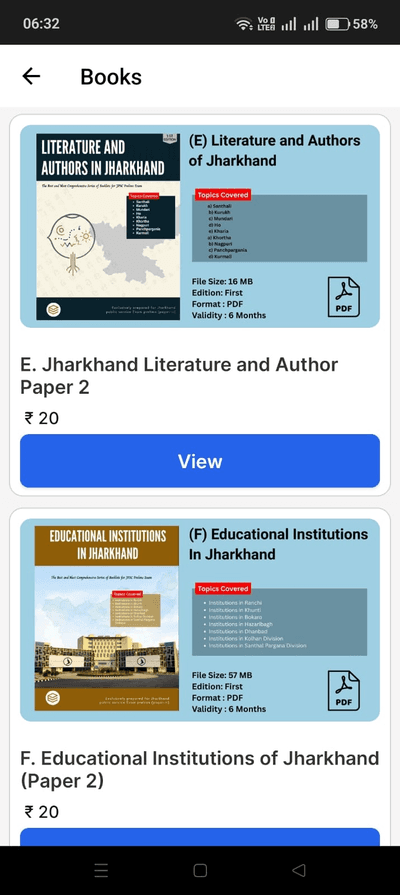

LearnPro offers comprehensive courses including UPSC Foundation Prime Batch, UPSC Prelims Test Series, Mains Answer Writing Programme, and optional subject courses. All programmes include live classes, test series, personal mentorship, and detailed study material.

LearnPro stands out with its bilingual teaching approach, advanced performance analytics, daily current affairs coverage, structured answer writing practice with expert feedback, and comprehensive coverage of UPSC, JPSC, BPSC, and other State PSC examinations under one platform.

Yes, we offer dedicated courses and study material for JPSC (Jharkhand), BPSC (Bihar), UPPSC, MPPSC, RPSC, WBPSC, APSC, and 12+ other State PSC examinations. Each course is tailored with state-specific syllabus coverage and bilingual content.

Yes! Our daily current affairs articles, editorials, monthly compilations, and subject-wise notes are freely accessible on our website. You can browse over 300+ articles covering all major topics relevant to UPSC and State PSC exams.

The programme includes daily answer writing practice, model answers from toppers and experts, detailed personal feedback on your answers, structured improvement plans, and GS + optional subject coverage. It helps you build the art of answer writing for UPSC & State PSC Mains.

All our live courses, test series, and recorded lectures are available on our learning platform at learnpro.live. You can visit the platform, browse available courses, and enroll directly. For any queries, call us at +91 9102557680.

Absolutely! We provide free daily current affairs, subject-wise UPSC notes in PDF format, previous year question analysis, monthly magazines, and topic-wise compilations. All these resources are available on our website without any registration.

Our Prelims Test Series includes 5000+ MCQs, full-length mock tests, sectional tests, and detailed performance analytics with All India Ranking. It helps you identify strengths and weaknesses, improve time management, and benchmark your preparation against thousands of aspirants.

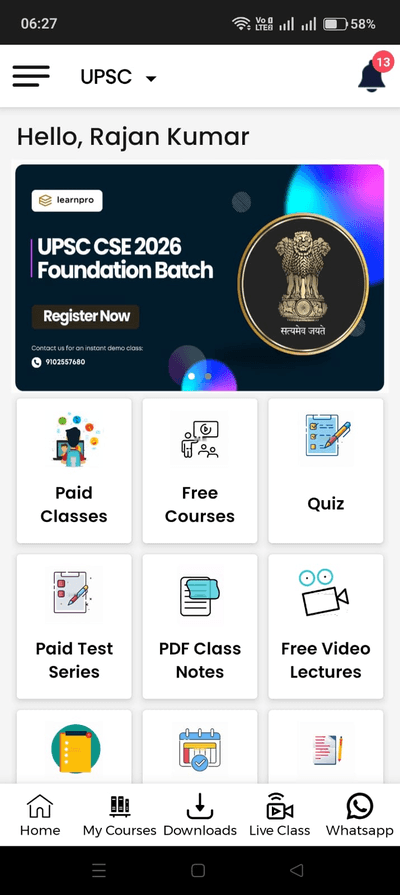

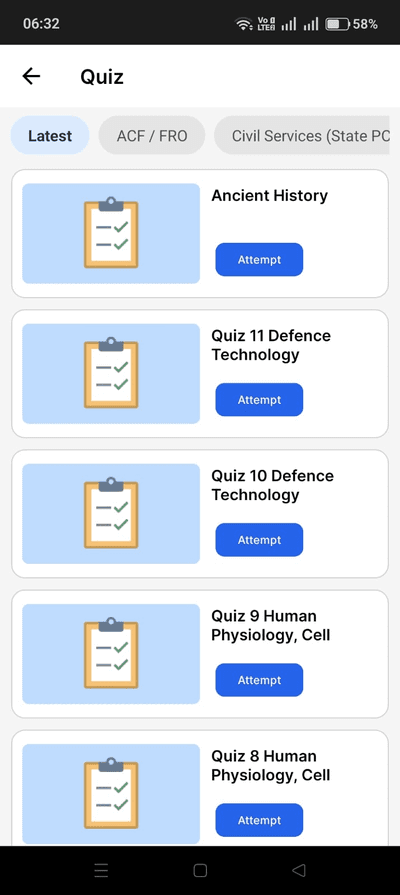

LearnPro App — Your Complete UPSC Journey in One App!

Access paid classes, free courses, quizzes, PDF notes, video lectures, and live classes — everything you need for UPSC and State PCS preparation, right on your phone.

GET IT ON

Google Play

Don't just be prepared... BE PREPARED!

Begin Your Academic Journey

Join an institution trusted by 50,000+ scholars. Structured academic programs, expert mentorship, and a proven track record across 72+ batches.