January 25, 2026 5:49 am

Introduction of The Ahom Dynasty in Assam

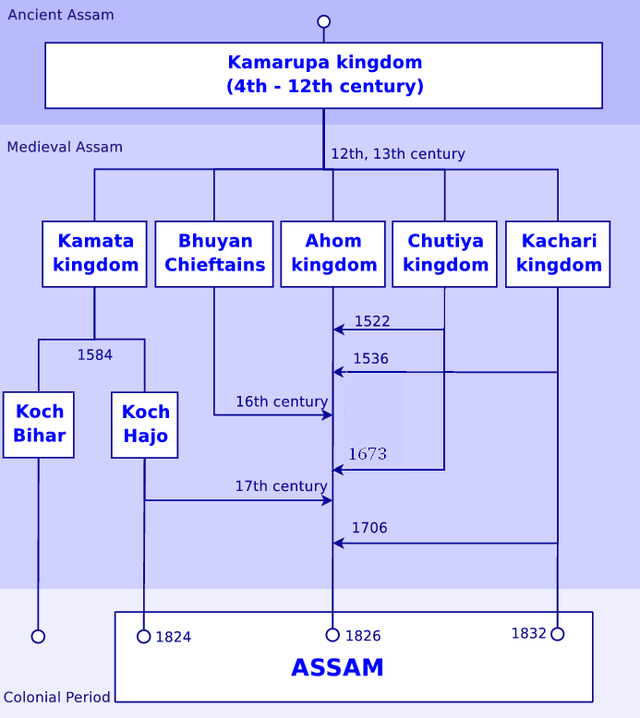

The Ahom Dynasty towers over the “History of Assam and Ahom rule,” a kingdom that governed the Brahmaputra Valley for nearly 600 years, from 1228 to 1826. Founded by Sukaphaa, a Tai prince from Mong Mao, the Ahoms arrived as outsiders but rooted themselves deeply, blending their Southeast Asian heritage with Assamese traditions. This dynasty wasn’t merely a political entity; it was a force of economic innovation, cultural richness, and military might, crafting an identity that persists in Assam today. From the strategic brilliance of the Battle of Saraighat to the intricate Paik system, the Ahoms built a legacy of resilience, only to succumb to the Moamoria Rebellion, Burmese invasions, and the Treaty of Yandabo.

What makes the Ahom Dynasty extraordinary? It thrived as a minority ruling elite, integrating diverse tribes while fending off Mughal and later Burmese threats. Its economic systems powered its armies, its art and culture enriched its people, and its eventual fall reshaped Assam under British rule. In this 3000-word exploration, we’ll trace its origins, rise, economic framework, cultural achievements, decline, and lasting impact. The Ahom Dynasty is a saga of triumph and transformation in the “History of Assam and Ahom rule,” a story waiting to be uncovered.

- APSC Notification 2025 OUT | APSC CCE 2025 Exam Date, Vacancy, Exam Pattern, Syllabus & Eligibility

- APSC Exam 2025: A Complete Guide for Aspirants

- APSC CCE Final Result 2023: Assam Public Service Commission Declares Results for Combined Competitive Examination

- APSC Result 2025: Date, Download PDF, and Merit List

- APSC Application Form 2025: Expected Release Date , How to Apply

- APSC Cut Off 2025: Expected Cut off, Everything You Need to Know

- APSC Exam 2025: Key Dates, Eligibility, Admit Card, Syllabus, and Exam Pattern

- APSC Syllabus 2025: Subject-Wise Topics for APSC Prelims, Mains, and Interview

Origins and Early Expansion

The “History of Assam and Ahom rule“ begins with the Ahom Dynasty’s birth in 1228, when Sukaphaa, a Tai prince from Mong Mao, crossed the Patkai hills into Assam. With a small retinue of warriors and nobles, he entered the Brahmaputra Valley, seeking fertile lands to establish a kingdom. Rather than conquering through brute force, Sukaphaa allied with local tribes—the Morans, Barahis, and Borahis—using diplomacy and selective battles to secure Upper Assam. His vision was a stable realm, blending Tai Ahom traditions like animism with indigenous ways.

In 1253, Sukaphaa founded the first Ahom capital at Charaideo, a hillock that became a sacred site, later adorned with maidams (royal tombs). His reign (1228–1268) focused on consolidation, appointing nobles and establishing a rudimentary hierarchy led by the Chao-Pha (king). Successors like Suteuphaa and Subinphaa pushed westward, subduing the Chutias and Kacharis through strategic marriages and tribute. By the 14th century, under Sudangphaa (1397–1407), the Ahoms adopted the title Swargadeo (heavenly king), signaling their permanence. This early growth laid the foundation for the “History of Assam and Ahom rule,” rooted in adaptability. Learn more about Sukaphaa at .

Rise to Power – The Golden Age

The Ahom Dynasty ascended to its peak between the 15th and 17th centuries, a golden age that defines the “History of Assam and Ahom rule.” This rise began with Suhungmung (1497–1539), the Dihingia Raja, who expanded the kingdom’s borders. He annexed the Chutia kingdom in 1523 and subdued the Kacharis in 1531, integrating their peoples into a multi-ethnic state. Suhungmung formalized the Paik system, assigning every male as a paik to serve as soldier, farmer, or laborer for land rights, strengthening the economy and military.

The dynasty’s greatest triumph came in 1671 with the Battle of Saraighat, led by Lachit Borphukan. Facing a Mughal invasion under Mir Jumla, Lachit harnessed the Brahmaputra’s currents and guerrilla tactics to secure a stunning victory. His leadership, even while ill, ensured Ahom dominance, a moment etched in Assam’s lore. Kings like Sukhrungphaa (1696–1714) later fortified this era, building defenses like Talatal Ghar. This golden age of military prowess and expansion cemented the Ahom Dynasty as a regional power in the “History of Assam and Ahom rule.” Explore this battle at ; dive into the Paik system at .

Economic System of the Ahoms

The Ahom Dynasty’s economic system was a linchpin of its dominance in the “History of Assam and Ahom rule,” underpinning nearly six centuries of rule over the Brahmaputra Valley. Far from a mere backdrop to its military and cultural achievements, this system was a dynamic engine that fueled the kingdom’s growth, sustained its armies, and shaped its society. At its core was the innovative Paik system, complemented by a robust agricultural base, strategic trade networks, and a taxation structure tailored to Assam’s geography and populace. Yet, this economic edifice, while a source of strength during the dynasty’s golden age, crumbled under later pressures, hastening the Ahom fall. Let’s delve into the intricacies of this system, exploring its mechanisms, successes, and eventual decline.

The Paik System: A Labor-Based Economy

The Paik system was the beating heart of the Ahom economy, a unique labor organization that intertwined military, agricultural, and administrative needs. Introduced in its rudimentary form by Sukaphaa and formalized under Suhungmung (1497–1539), it transformed every able-bodied male into a paik, a worker bound to serve the state. This system was both a strength and a social contract, ensuring resource allocation without a monetary economy in the early centuries.

- Structure and Organization:

- Society was divided into khels, units of 100–1000 paiks, each overseen by officers like the Bora or Saikia.

- Paiks rotated duties—typically one-third served actively (e.g., as soldiers or laborers), while two-thirds worked their assigned lands, producing food and goods.

- Nobles such as the Borphukan and Burhagohain managed higher oversight, reporting to the Swargadeo.

- Land Allocation:

- Each paik received a plot of land (about 2–3 puras, roughly 6–9 acres) as payment, exempt from monetary taxes but tied to service obligations.

- This land tenure system incentivized productivity while binding individuals to the state, creating a self-sustaining cycle.

- Flexibility and Scale:

- During wars, such as the Battle of Saraighat (1671), the Paik system mobilized thousands instantly, showcasing its scalability.

- In peacetime, it built infrastructure—roads, tanks, and fortifications like Talatal Ghar—demonstrating its versatility.

The Paik system was a marvel of efficiency, enabling the Ahoms to maintain a standing army and a productive peasantry without coinage until the 17th century. It reflected a centralized yet decentralized approach, balancing royal control with local autonomy under Chaudhuries.

Agriculture: The Economic Bedrock

Agriculture formed the backbone of the Ahom economy, thriving in the fertile Brahmaputra Valley. The paiks cultivated crops that sustained both the kingdom and its trade, leveraging Assam’s monsoon-fed plains.

- Wet-Rice Cultivation:

- The primary crop was rice, grown using wet-rice techniques suited to the valley’s floodplains. Varieties like bao dhan (deep-water rice) thrived during seasonal inundations.

- Paiks managed irrigation through small canals and bunds, a legacy of Tai agricultural knowledge adapted to Assam.

- Secondary Crops and Products:

- Mustard, pulses, and betel nut supplemented diets and trade, while mulberry trees supported sericulture (silk production).

- Forests yielded timber, bamboo, and elephant tusks—valuable exports that enriched royal coffers.

- Economic Stability:

- Surpluses from bumper harvests, especially under kings like Sukhrungphaa (1696–1714), funded grand projects like Rang Ghar and strengthened the treasury.

- Famines were rare until the 18th century, reflecting agricultural resilience tied to the Paik system.

This agrarian focus made the Ahom economy self-reliant, with paiks doubling as farmers and soldiers, ensuring food security and military readiness—a dual role that defined the “History of Assam and Ahom rule.”

Trade Networks: Connecting Assam to the World

While agriculture dominated, trade amplified the Ahom economy, linking Assam to regional markets. The Brahmaputra River served as a vital artery, facilitating commerce despite the kingdom’s initial isolation.

- Key Trade Goods:

- Exports included muga silk, ivory, agarwood, and rice, prized in Bengal and Tibet.

- Imports comprised salt (scarce in Assam), cotton, and luxury goods like gold from Mughal territories.

- Trade Routes and Partners:

- Riverine trade via the Brahmaputra connected to Bengal’s ports, with Ahom boats navigating to Dhaka and beyond.

- Overland routes through the Patkai hills linked to Burma and China, though less developed until later centuries.

- Economic Impact:

- Trade revenue, though secondary to agriculture, enriched the nobility and funded military campaigns, such as against the Mughals.

- Under Rudra Singha (1696–1714), coinage emerged—octagonal rupees—reflecting growing commercial sophistication.

Trade bolstered the Ahom economy, complementing the Paik system by injecting wealth into a largely agrarian state, though it remained a smaller pillar compared to land-based production.

Taxation and Resource Management

The Ahom taxation system was minimalist yet effective, designed to extract resources without overburdening the populace.

- In-Kind Contributions:

- Paiks paid no cash taxes; instead, they offered labor or a portion of their harvest (e.g., rice or silk).

- Villages contributed goods like honey, mats, or boats, collected by Rajkhowas.

- Centralized Control:

- The Swargadeo and Gohains oversaw granaries and armories, storing surpluses for emergencies or war.

- Artisans, organized into khels, produced weapons and tools, reducing reliance on imports.

- Economic Balance:

- This system avoided monetary strain, aligning with the Paik labor model, but limited liquidity until coinage appeared.

This light taxation sustained the kingdom’s needs while preserving peasant loyalty, a delicate balance that held until external pressures mounted.

Decline and Collapse

The Ahom economy thrived until the 18th century, when internal and external forces unraveled it.

- Moamoria Rebellion (1769–1805):

- The revolt disrupted the Paik system, as many fled to sattras, halving the workforce and agricultural output.

- Rangpur’s repeated sieges drained reserves, signaling economic distress.

- 18th-Century Stagnation:

- Trade routes shifted, and poor harvests under kings like Siba Singha (1714–1744) weakened surpluses.

- Royal extravagance, such as Phuleswari’s temple projects, strained resources.

- Burmese Invasions (1817–1826):

- Konbaung forces ravaged fields and markets, collapsing agriculture and trade.

- The Treaty of Yandabo (1826) ended Ahom control, ceding Assam to the British.

By the 19th century, the Ahom economic system—once a model of self-sufficiency—lay in ruins, a victim of rebellion, mismanagement, and invasion. Its collapse marked a turning point in the “History of Assam and Ahom rule,” paving the way for colonial exploitation.

Art and Culture Under the Ahoms

The Ahom Dynasty’s reign in the “History of Assam and Ahom rule” was not just a tale of conquest and governance; it was a vibrant era of artistic expression and cultural synthesis that left an indelible mark on Assam. Spanning nearly 600 years, the Ahoms transformed the Brahmaputra Valley into a crucible where Tai traditions melded with indigenous Assamese practices, enriched by influences like Hinduism and neo-Vaishnavism. From architectural marvels to literary chronicles, from festivals to performing arts, their cultural legacy reflects a kingdom that valued creativity as much as power. This section explores the breadth of Ahom art and culture, revealing how it shaped Assam’s identity and endured beyond the dynasty’s fall.

Architectural Achievements: Monuments of Power and Grace

The Ahoms were master builders, their architecture blending utility with aesthetic brilliance. These structures, rooted in Tai engineering and adapted to Assam’s landscape, stand as testaments to their ingenuity.

- Rang Ghar:

- Constructed in 1744 under Pramatta Singha, this two-story amphitheater, shaped like an inverted boat, is dubbed “Asia’s first sports pavilion.”

- Built with brick and an indigenous mortar of rice paste and duck eggs, it hosted royal events—Bihu celebrations, buffalo fights—symbolizing cultural patronage.

- Its arched entrances and sloping roof showcase Ahom architectural flair, preserved today as a heritage site.

- Charaideo Maidams:

- Located at the dynasty’s first capital, Charaideo, these pyramid-like burial mounds entombed Swargadeos and nobles, reflecting Tai ancestor worship.

- Made of earth and brick, often with underground chambers, they signify a spiritual continuity, later designated a UNESCO tentative site.

- Talatal Ghar:

- Begun by Rudra Singha (1696–1714) and expanded by successors, this multi-level palace in Rangpur combined defense (secret tunnels) with residence.

- Its seven stories—three underground—demonstrate strategic design, blending Tai minimalism with local craftsmanship.

These edifices weren’t mere buildings; they were cultural statements, embodying the Ahom ethos of permanence and prestige in the “History of Assam and Ahom rule.”

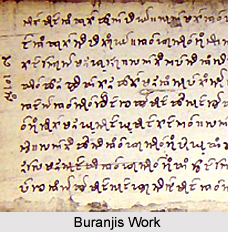

Literary Legacy: The Buranjis

The Ahoms nurtured a rich literary tradition, most notably through the Buranjis, historical chronicles that documented their reign with meticulous detail.

- Nature and Purpose:

- Written on sanchi bark or paper in Tai-Ahom and later Assamese, Buranjis recorded reigns, battles (e.g., Battle of Saraighat), and diplomacy.

- Commissioned by Swargadeos, they served as official histories, blending narrative with administrative records.

- Key Examples:

- The Assam Buranji details Sukaphaa’s arrival to the 17th century, while the Deodhai Assam Buranji covers later reigns.

- Their prose, factual yet vivid, preserved oral traditions, offering historians a window into Ahom life.

- Cultural Impact:

- They fostered Assamese as a literary language, bridging Tai and indigenous dialects, a legacy enduring in modern Assam.

The Buranjis are more than texts; they’re cultural artifacts, anchoring the Ahom Dynasty’s story in the “History of Assam and Ahom rule.”

Religious and Cultural Synthesis

The Ahoms arrived with Tai animism—worshipping ancestors and nature spirits—but embraced Hinduism and neo-Vaishnavism, creating a pluralistic culture.

- Adoption of Hinduism:

- Under Suhungmung (1497–1539), the Ahoms adopted Hindu names (e.g., Swargadeo) and Shaktism, building temples like Kamakhya.

- Kings like Siba Singha (1714–1744) and Phuleswari reinforced Shakta rituals, though this sparked tensions with Vaishnavas.

- Neo-Vaishnavism’s Rise:

- Srimanta Sankardeva’s 16th-century movement, supported by Ahom rulers like Suklenmung, spread egalitarian ideals via sAttachras.

- This fostered a cultural renaissance—devotional music, poetry, and community identity—softening the Paik system’s rigidity.

- Cultural Harmony:

- The blend of Tai ancestor rites, Hindu festivals, and Vaishnava bhakti created a unique Assamese ethos, celebrated in modern times.

This synthesis enriched the Ahom cultural landscape, a fusion detailed at .

Performing Arts and Festivals

The Ahoms elevated performing arts and festivals, embedding them in Assam’s cultural fabric.

- Bihu:

- Though pre-Ahom, this agrarian festival—Rongali Bihu (spring), Kongali Bihu (harvest), Bhogali Bihu (feast)—flourished under royal patronage.

- Ahom kings hosted grand Bihu events at Rang Ghar, with dances and songs reflecting rural life.

- Theatre and Music:

- Sankardeva’s Bhaona, devotional plays with masks and music, gained traction, blending Vaishnava themes with Ahom support.

- Instruments like the gogona and pepa, alongside Tai drums, enriched performances.

- Royal Patronage:

- Kings like Rudra Singha organized cultural spectacles, reinforcing communal bonds and royal prestige.

These arts weren’t mere entertainment; they were expressions of Ahom identity, uniting diverse peoples under a shared heritage.

Craftsmanship and Material Culture

Ahom artisans excelled in crafts, producing goods that reflected both utility and artistry.

- Textiles:

- Muga silk, a golden-hued fabric, was woven by paiks and traded regionally, a hallmark of Assamese craftsmanship.

- Intricate designs adorned royal garments, showcasing weaving skills.

- Metallurgy and Woodwork:

- Blacksmiths forged swords and cannons, vital for wars like Saraighat, while carpenters crafted boats and furniture.

- The octagonal rupee, introduced by Rudra Singha, marked a leap in metallurgy.

- Everyday Art:

- Pottery, bamboo mats, and lacquered items adorned homes, blending Tai simplicity with local flair.

This craftsmanship underscored the Ahom economy’s diversity, supporting both trade and cultural pride.

Decline and Cultural Endurance

The Ahom cultural zenith waned with the dynasty’s decline. The Moamoria Rebellion disrupted sattras and royal patronage, while Burmese invasions razed cultural sites. The Treaty of Yandabo (1826) shifted Assam to British hands, diluting Ahom influence. Yet, their art and culture endured—Bihu thrives, Buranjis inform, and Rang Ghar stands tall.

Challenges and Decline

The Ahom Dynasty’s decline in the “History of Assam and Ahom rule” was a slow unraveling of a kingdom that had once stood as a beacon of power in the Brahmaputra Valley. After centuries of resilience, the 18th and early 19th centuries brought challenges that eroded its foundations—internal rebellions, external invasions, and the encroachment of colonial forces. These trials, culminating in the Treaty of Yandabo in 1826, marked the end of Ahom sovereignty, closing a 600-year chapter with a dramatic fall from grace.

The first and most devastating blow came with the Moamoria Rebellion (1769–1805), a socio-religious uprising that shook the core of Ahom rule. Rooted in tensions between the neo-Vaishnavite Moamorias—followers of the Mayamara Sattra—and the Shakta-leaning monarchy, the rebellion erupted in 1769 when Kirtichandra Barbarua, a tyrannical noble, flogged Moran leaders Ragha Moran and Nahar Khora. The Moamorias retaliated, capturing the Ahom capital, Rangpur, twice—first in 1769 and again in 1788—imprisoning kings like Lakshmi Singha and forcing Gaurinath Singha to flee. This revolt wasn’t just a military setback; it shattered the Paik system, as thousands defected to sattras, halving the population and crippling the economy. The establishment of the semi-independent Matak Rajya under Sarbananda Singha further fragmented the kingdom, signaling an irreparable loss of unity.

Weakened by internal strife, the Ahoms faced a relentless external threat: the Burmese invasions (1817–1826). The Konbaung Dynasty, under King Bagyidaw, exploited Assam’s vulnerability, launching three devastating campaigns. The first, in 1817, was orchestrated by Badan Chandra Borphukan, a treacherous Ahom noble who invited Burmese forces to settle a succession dispute between Chandrakanta Singha and Purandar Singha. The invaders overran Assam, deposing Chandrakanta and plunging the region into chaos with massacres, famine, and destruction. By 1821, the Burmese had entrenched their occupation, reducing the Ahom monarchy to a puppet state. The once-thriving economy—fields, markets, and trade routes—lay in ruins, leaving the kingdom defenseless.

The final chapter unfolded with the First Anglo-Burmese War (1824–1826), a conflict between the British East India Company and Burma that sealed the Ahom fate. Unable to resist, Chandrakanta and his successors watched as the British, under Major General Archibald Campbell, defeated the Burmese. The Treaty of Yandabo, signed on February 24, 1826, ceded Assam to the British, formally dissolving the Ahom kingdom. The Swargadeos, once revered as heavenly kings, were reduced to pensioned relics, their authority extinguished by a colonial power eager to exploit Assam’s resources. This treaty marked the end of the “History of Assam and Ahom rule” as an independent narrative, a fall precipitated by rebellion and invasion. .

The Ahom decline was a tragic convergence of internal discord and external aggression, a kingdom undone by its own fissures and the ambitions of others. From the ashes of Rangpur to the ink of Yandabo, this period illustrates the fragility of even the mightiest dynasties when faced with unrelenting challenges.

Legacy of the Ahom Dynasty

The Ahom Dynasty’s legacy in the “History of Assam and Ahom rule” is a profound testament to its 600-year reign, a thread that weaves through Assam’s modern identity despite the kingdom’s fall in 1826. Though the Treaty of Yandabo ended its political sovereignty, the Ahoms left an enduring imprint on Assam’s culture, administration, and collective memory. From architectural relics to linguistic roots, from festivals to social structures, their influence persists, a bridge between a medieval past and a contemporary present.

Culturally, the Ahoms shaped Assam into a vibrant mosaic. Their integration of Tai traditions with indigenous practices fostered the Assamese language, enriched by Tai-Ahom vocabulary and preserved in Buranjis, the historical chronicles that remain vital historical sources. The Bihu festival, though pre-dating the Ahoms, flourished under their patronage, with kings like Pramatta Singha hosting grand celebrations at Rang Ghar. This agrarian festival, with its dances and songs, embodies a communal spirit the Ahoms nurtured. The rise of neo-Vaishnavism, championed by Srimanta Sankardeva and supported by rulers like Suklenmung, left a spiritual legacy of egalitarianism, its sattras still dotting Assam’s landscape. These cultural contributions—language, festivals, and faith—form the bedrock of Assam’s identity, a gift from the Ahom era.

Administratively, the Ahom model of governance echoes in Assam’s systems. The Paik system, though dismantled, influenced land tenure practices under British and post-independence rule, while titles like Burhagohain and Borphukan linger in historical discourse. The Ahoms’ multi-ethnic approach—integrating Morans, Kacharis, and Chutias—set a precedent for Assam’s diverse society, a legacy of unity amidst variety that resonates today.

Physically, the Ahoms left a tangible heritage in their architectural marvels. Charaideo Maidams, the royal tombs at the dynasty’s first capital, stand as silent sentinels of Swargadeo glory, recognized on UNESCO’s tentative list. Rang Ghar, with its elegant arches, and Talatal Ghar, with its secret tunnels, draw tourists and scholars, preserving Ahom craftsmanship. These sites, alongside artifacts like muga silk textiles and octagonal rupees, offer a glimpse into a sophisticated past, anchoring Assam’s tourism and pride.

The Ahom legacy also lives in memory and narrative. The valor of Lachit Borphukan at the Battle of Saraighat inspires patriotism, celebrated annually on Lachit Divas. The Ahom resistance against Mughals, Burmese, and internal foes like the Moamorias fuels a narrative of resilience, a source of inspiration for Assamese identity. Even after the British annexation, the Ahom spirit persisted, influencing movements for cultural preservation and regional autonomy in modern India.

Politically, the Ahom fall marked Assam’s integration into broader India, but their legacy transcends this loss. The dynasty’s ability to govern a diverse realm for six centuries offers lessons in adaptability and leadership, studied by historians and policymakers alike. In the “History of Assam and Ahom rule,” the Ahoms are not just a fallen kingdom but a living heritage, their influence woven into Assam’s festivals, languages, and landmarks.

The Ahom Dynasty may have faded with Yandabo, but its echoes remain loud—proof that a kingdom’s true measure lies not in its duration, but in the depth of its imprint on the land and its people.