January 25, 2026 4:29 am

Defining Megaliths: Understanding Ancient Stone Monuments

The term megalith comes from the Greek words megas (great) and lithos (stone), referring to large stone structures or monuments. However, not every monument made of big stones qualifies as a megalith. The term has a specific archaeological usage, denoting structures associated with burial, commemoration, or rituals. Hero stones or memorial stones, though monumental, are excluded from this category. Typically, megaliths are large-stone burial sites located away from habitation areas. These ancient structures serve as invaluable records of past cultures, shedding light on ritualistic and social practices.

Chronology of Megalithic Cultures in India

Megalithic culture in India is dated primarily between 1000 B.C. and A.D. 100, with its peak popularity observed between 600 B.C. and A.D. 100. The chronology, however, varies across regions:

- South India:

- Hallur (Karnataka): Radiocarbon dating places megalithic habitation as early as 1000 B.C.

- Tadakanahalli graves correlate with the earliest phases of Hallur.

- Paiyampalli (Tamil Nadu): Dates around the 4th century B.C.

- North Karnataka: Some sites are dated as early as 1200 B.C.

- Vidarbha Region (Maharashtra):

- Sites like Naikund and Takalghat provide dates around 600 B.C.

- Cultural Overlaps:

The megalithic culture in South India overlaps with the late Neolithic-Chalcolithic phase at the lower end and the use of Rouletted Ware (first millennium A.D.) at the upper end. This dynamic interaction reflects a complex societal and technological evolution.

Despite limited radiocarbon data, these findings help frame a time span that highlights regional variations and the widespread influence of megalithic cultures.

Origin and Spread of Megalithic Cultures

The origins of Indian megalithic cultures are often linked to the Dravidian-speaking communities who migrated to South India from West Asia by sea. However, unlike West Asian megaliths (which are part of the Bronze Age), Indian megaliths belong to the Iron Age, generally dated to 1000 B.C. onwards. This significant material and chronological difference raises questions about the exact timeline of the culture’s arrival and spread.

Routes of Spread:

- Sea Route: From the Gulf of Oman to India’s west coast.

- Land Route: Through Iran into northern and central India.

The mingling of traditions and practices over time created a diverse range of burial practices, leading to the development of megalithic structures across the subcontinent.

Geographical Distribution of Megalithic Sites

Megalithic sites are spread across India’s varied landscapes, with a notable concentration in the Deccan region, south of the Godavari River. These structures reflect regional traditions and societal practices, found in areas like:

| Region | Key Features | Examples of Sites |

|---|---|---|

| South India | Dominant region for megalithic culture, marked by sepulchral monuments such as cists, dolmens, cairn circles, and urn burials. | Adichanallur (Tamil Nadu), Brahmagiri (Karnataka), Nagarjunakonda (Andhra Pradesh), Marayur (Kerala) |

| Central India | Presence of large-stone structures and burial monuments, reflecting cultural similarities with southern practices. | Junapani (Vidarbha), Takalghat (Maharashtra) |

| North India | Scattered megalithic sites with significant stone structures, often differing in style from southern traditions. | Seraikala (Bihar), Deodhoora (Almora, Uttarakhand), Khera (Fatehpur Sikri, Uttar Pradesh) |

| Western India | Features cairn circles and burial mounds, showing a western extension of megalithic culture. | Deosa (near Jaipur, Rajasthan) |

| Himalayan Region | Evidence of megalithic practices in high-altitude areas, including stone circles and burial pits. | Burzahom (Jammu and Kashmir), Leh (Himalayas) |

The wide distribution of megalithic sites indicates their importance in ancient Indian society. However, their greatest development and density remain focused in South India, suggesting the region was a cultural and ritual hub for these practices.

Sepulchral Megaliths: Burial Practices and Variations

Megalithic burial practices often revolved around sepulchral monuments, which preserved the remains of the dead in different forms. These structures provide significant insights into the beliefs and rituals of ancient societies.

Types of Burials:

- Primary Burials:

- The deceased was interred shortly after death.

- Often includes a complete skeleton alongside offerings such as pottery, weapons, or ornaments.

- Sometimes placed within a terracotta sarcophagus, offering detailed archaeological evidence.

- Secondary Burials:

- Bones or remains of the deceased were collected and stored in urns or pits.

- These graves typically mark ritualistic commemorations rather than immediate burial.

Marking the Burial Site:

- Stone circles, cairns, or slab enclosures commonly marked the burial spots.

- Occasionally, the area was isolated with stone boundaries, emphasizing its sacred significance.

These practices highlight a deep connection between death rituals and cosmological beliefs, as megaliths were often seen as conduits between the living and the afterlife.

Cultural and Technological Significance of Megalithic Cultures

The megalithic culture represents a crucial phase in Indian history, bridging the Neolithic-Chalcolithic and Iron Age cultures. Their widespread construction and diversity underline advancements in iron technology, agriculture, and social organization.

Key Features:

- Iron Tools and Implements:

- The use of iron tools marked a technological leap, enabling more efficient farming and warfare.

- Iron’s association with megalithic sites indicates its integral role in societal evolution.

- Ritualistic and Social Practices:

- The complex burial customs reflect a belief in the afterlife and societal stratification.

- The presence of grave goods, often including weapons and ornaments, suggests hierarchical structures.

- Cultural Exchange:

- The similarities between Indian and West Asian megaliths hint at ancient trade and cultural connections.

- However, Indian megaliths’ chronological and material differences highlight localized developments.

Regional Variations and Legacy

While megalithic practices are found throughout India, they exhibit significant regional variations, influenced by local traditions and resources.

- South India: Rich burial traditions with distinct grave markers like stone circles and cairns.

- North-East India: Megaliths remain a living tradition among certain tribes in the region.

- Central and Western India: Scattered large-stone structures reflecting localized practices.

Megalithic practices in South India represent the culture’s peak development, thriving for nearly a millennium. This regional focus underscores its significance in shaping the Deccan’s prehistoric and early historic society.

Megaliths and Archaeological Insights

Megalithic monuments are invaluable to archaeologists, offering detailed records of ancient cultures. From burial practices to technological innovations, they provide a window into past societies.

What Megaliths Reveal:

- Technological Progress:

- The widespread use of iron tools suggests a significant technological transition.

- Social Structures:

- Elaborate burials and grave goods hint at hierarchical societies.

- Belief Systems:

- Burial customs reflect ritualistic beliefs in the afterlife and cosmology.

Megalithic studies are crucial for understanding the transition from prehistory to early history, particularly in South India.

Megalithic Culture – The Iron Age Culture of South India

The megalithic culture in South India represents a fully developed Iron Age society where the use of iron significantly transformed daily life. The widespread adoption of iron as a material for tools and weapons gradually replaced the reliance on stone, while stones found new utility in rituals and social practices.

Key Features of South Indian Megalithic Culture:

- Iron Usage:

Iron objects were universally present across all megalithic sites, from Junapani near Nagpur (Central India) to Adichanallur in Tamil Nadu. This marked a technological advancement that influenced agriculture, tools, and societal structures. - Burial Practices:

A defining feature of this culture was its elaborate methods of disposing of the dead. The deceased were no longer buried near their homes but in cemeteries or graveyards, signifying a shift in ritualistic practices.- Bones were placed in specially crafted stone boxes called cists.

- Cists were elaborate, requiring skilled masons and community cooperation for their construction.

- These burial sites reflected meticulous planning and were likely prepared in advance of an individual’s death.

- Community Organization:

The construction of megaliths necessitated a high degree of planning, collaboration, and craftsmanship, highlighting a structured society with skilled workers, including masons capable of shaping large stones for ritualistic purposes. - Cultural Shift:

The introduction of iron tools and weapons led to a gradual change in societal organization, agriculture, and rituals, while traditional practices like house plans remained largely unchanged.

Archaeological Importance:

Most knowledge about the Iron Age in South India stems from the excavations of megalithic burials, offering insights into the cultural practices, technological progress, and societal organization of the era.

This unique and elaborate burial culture of South India not only illustrates the technological leap brought by iron but also reflects the ritualistic and social intricacies of the megalithic communities.

Classification of the Megaliths

The megalithic culture in India shows a variety of methods for the disposal of the dead. Moreover, there are megaliths which are internally different but exhibit the same external features. The megaliths can be classified under different categories:

- Rock Cut Caves

- Hood Stones and Hat Stones / Cap Stones

- Menhirs, Alignments, and Avenues

- Dolmenoid Cists

- Cairn Circles

- Stone Circles

- Pit Burials

- Barrows

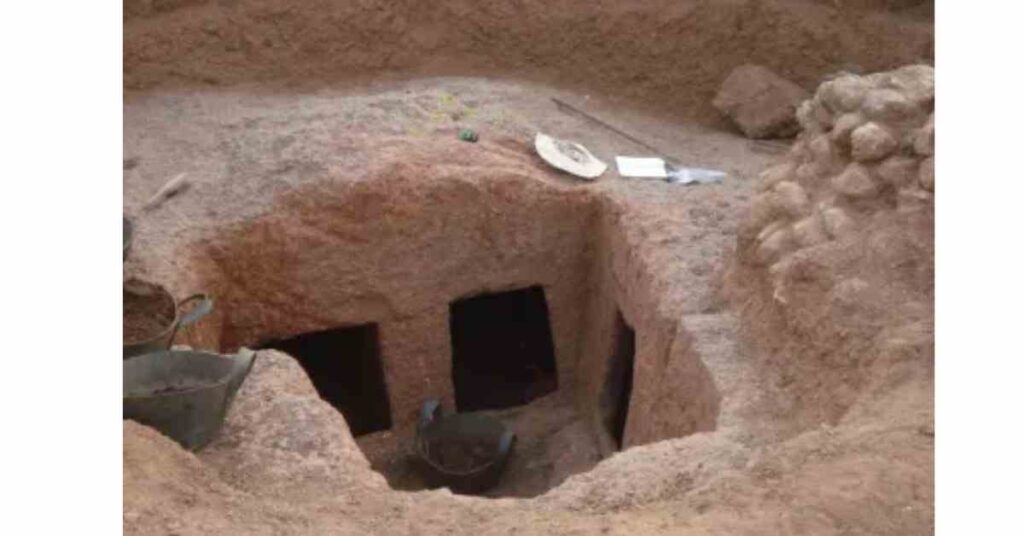

1. Rock Cut Caves

These are scooped out on soft laterite rock, as found in the southern part of the West Coast. These rock cut cave tombs are peculiar to this region and occur in the Cochin and Malabar regions of Kerala. The laterite rock cut caves of the burial site constitute three chambers.

They also occur in other regions. On the East Coast of South India, they are present in Mamallapuram near Madras. These rock cut burial caves in the Cochin region are of four types:

(i) Caves with Central Pillar.

(ii) Caves without Central Pillar.

(iii) Caves with a Deep Opening.

(iv) Multi-Chambered Caves.

2. Hood Stones (Kudaikallu) and Cap Stones (Toppikkal)

Allied with the rock cut caves but of a simpler form are the Hood Stones or Kudaikallu, mostly found in Kerala. These consist of a dome-shaped dressed laterite block which covers the underground circular pit cut into a natural rock and provided with a stairway.

In some cases, the hood stone gives place to a cap stone or toppikkal, which is a plano-convex slab resting on three or four quadrilateral boulders. This also covers an underground burial pit containing the funerary urn and other grave furnishings.

Unlike in the rock cut caves, there is no chamber apart from this open pit, in which itself the burial is made. Usually, it contains:

- A burial urn covered with a convex or dome-shaped pottery lid or a stone slab.

- Skeletal remains.

- Small pots and sometimes ashes.

Similar monuments are commonly encountered in Cochin and Malabar regions, extending along the Western Ghats into the Coimbatore region up to the Noyyal River valley in Tamil Nadu.

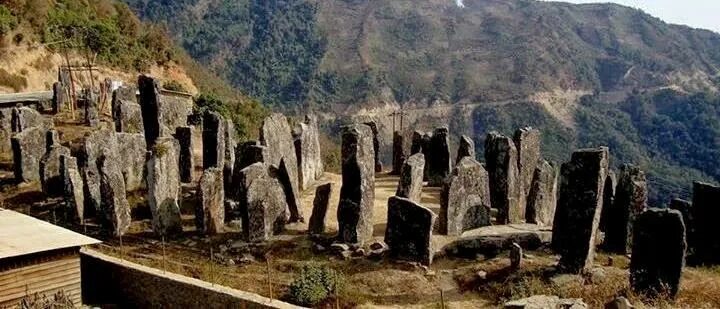

3. Menhirs, Alignments, and Avenues

Menhirs are monolithic stone pillars planted vertically into the ground. They range from small to gigantic heights and can either be dressed or left undressed. These commemorative stone pillars are typically associated with burial sites and serve as markers of significance. In ancient Tamil literature, they are referred to as nadukal and are often called Pandukkal or Pandil.

At some locations, such as Maski, menhirs are not planted but rest on the ground, supported by rubble. Menhirs are commonly found in close proximity to other types of megalithic burials, especially in Kerala, and the Bellary, Raichur, and Gulbarga regions of Karnataka, though they are less frequent in other parts of South India.

Prominent examples include:

- Mizoram’s Vangchhia village, where 171 menhirs stand in Kawtchhuah Ropui (The Great Entranceway).

- Meghalaya, Nagaland, and Andhra Pradesh also host scattered menhirs.

Alignments, closely related to menhirs, feature rows of standing stones, often dressed. Notable sites include Komalaparathala in Kerala and locations in Karnataka, such as Gulbarga, Raichur, and Mahboobnagar. Avenues, formed by two or more parallel rows of alignments, represent another distinctive category.

4. Dolmenoid Cists

Dolmenoid cists are rectangular or square box-like burial structures made of several orthostats (upright stones or slabs). These structures are topped with capstones, which can be composed of one or more stones. The floors are often paved with stone slabs.

Key features:

- Orthostats and capstones may be rough, undressed stones or partially dressed slabs.

- Found extensively in Sanur near Chingleput (Tamil Nadu) and across South India.

Subtypes in Tamil Nadu:

- Dolmenoid cist with multiple orthostats.

- Cist with four orthostats and U-shaped portholes on the east or west.

- Cist with portholes on the top corner of the eastern orthostat.

- Cist surrounded by slab circles.

Dolmens of Marayur in Kerala, known for their ancient rock paintings, represent a notable example. These dolmens highlight the engineering and ritualistic complexities of the megalithic culture in India.

5. Cairn Circles

Cairn circles are among the most prevalent megalithic structures in South India, often found alongside other types of burials. They consist of heaps of stone rubble enclosed within a circle of boulders.

Key characteristics:

- Burial pits beneath the cairn circles are typically circular, square, or oblong.

- Skeletal remains and grave goods are placed on the pit floors.

- Pits are filled with earth, and the cairn heap rises up to 3–4 feet above ground, bounded by stone circles.

Examples include:

- Megalithic burial sites in Veeranam (Tiruvannamalai district, Tamil Nadu), dated between 1000 BCE and 300 CE.

- Sites in Chingleput (Tamil Nadu), Chitradurg, and Gulbarga (Karnataka).

Cairn circles represent the widespread cultural and ritualistic practices of the megalithic culture in India, emphasizing the significance of honoring the dead through intricate burial constructions.

A Sarcophagus in Megalithic Culture

A sarcophagus, literally a legged coffin made of terracotta, is a distinct feature of megalithic burials in India, particularly within cairn circles. Sarcophagi entombments are more widespread compared to pit burials. Unlike pit burials, these contain skeletal remains and primary deposits of grave goods placed in an oblong terracotta sarcophagus.

Key characteristics:

- Sarcophagi are often provided with a convex terracotta lid, rows of legs at the bottom, and sometimes a capstone at a higher level.

- These structures showcase advanced craftsmanship and ceremonial complexity within the megalithic culture of India.

Prominent locations for sarcophagi include:

- South Arcot, Chingleput, and North Arcot districts in Tamil Nadu.

- Kolar district in Karnataka.

- A notable sarcophagus was unearthed from Pallavaram in Kancheepuram district, Tamil Nadu.

Urn Burials in Cairn Circles

Urn burials, a variant of sarcophagi burials, are widespread across South India. These burials involve pots or urns deposited in pits dug into the soil, often accompanied by a capstone and marked by a heap of cairns.

Key locations for urn burials include:

- Tamil Nadu: Found in districts like Madurai, Tiruchirapalli, Coimbatore, Nilgiris, Salem, Chingleput, and South Arcot.

- Karnataka: Kolar, Bangalore, Hassan, Chitradurg, Bellary, Raichur, and Gulbarga districts.

- Andhra Pradesh and Nagpur region: Significant finds also point to trade connections, as urns in Adichanallur resemble those from Malwa, Madhya Pradesh.

6. Stone Circles

Stone circles are the most commonly encountered megalithic monuments in India, encompassing various forms such as cairns, menhirs, dolmenoid cists, and others. These are found across:

- The southern tip of the Indian peninsula.

- Regions extending up to Nagpur and parts of North India.

In this context, the term refers specifically to stone circles without significant cairn fillings. These structures typically mark burial pits, which may or may not contain urns or sarcophagi.

7. Pit Burials

Pit burials involve large conical jars (pyriform or fusiform urns) containing funerary deposits buried in specially dug pits. Unlike other megalithic monuments, these lack visible surface markers like cairns, stone circles, hood stones, or menhirs.

Key characteristics:

- These burials exhibit traits of the megalithic culture of South India, such as the use of Black-and-Red Ware (BRW) pottery and associated iron objects.

- They are identical to regular megalithic burials except for the absence of surface markers.

Prominent locations:

- Tamil Nadu: Adichanallur, Gopalasamiparambu, and other sites.

- Karnataka and Andhra Pradesh: Found less frequently but still significant.

- North India: Observed at Harappan and Later Chalcolithic sites, though their context differs from South Indian practices.

These urn burials, including those without megalithic appendages, provide valuable insights into the funerary practices and material culture of megalithic societies in India.

8. Barrows

Barrows, or earthen mounds, are distinctive markers of megalithic burials in India, indicating underground burial sites. These mounds may take various forms:

- Circular Barrows: Rounded in shape.

- Oblong Barrows: Elongated in plan.

- Long Barrows: Extended, linear formations.

Barrows may or may not feature surrounding stone circles or ditches, serving as external markers for the burial site. While not widespread in India, barrows have been observed in specific locations, such as the Hassan district in Karnataka. These structures highlight the diversity of burial practices within the megalithic culture in India.

Grave Goods in Megalithic Burials

Grave goods from megalithic burials provide invaluable insights into the megalithic culture of India, reflecting the social, technological, and ritualistic aspects of ancient societies. The tradition of equipping burials with essential items stems from the belief in the afterlife, with the dead being provided with necessities for their existence beyond death.

Key Findings in Indian Megaliths:

- Pottery:

A diverse range of pottery types is commonly found in megalithic burials, showcasing the craftsmanship of the period. - Weapons and Implements:

- Predominantly made of iron, though stone and copper tools are also found.

- These items indicate advancements in tool-making and their importance in the lives of megalithic societies.

- Ornaments:

- Jewelry crafted from semi-precious stones, terracotta, shell, copper, and gold.

- Beads strung into necklaces or bracelets, with rare findings of ear ornaments, armlets, or diadems.

- Food Offerings:

- The presence of paddy husk, chaff, and other cereals suggests that food was placed in graves as offerings, reflecting the belief in sustaining the deceased in the afterlife.

- Animal Remains:

- Skeletal remains of animals, occasionally complete, are found in some graves, highlighting their ritualistic or symbolic importance.

Significance of Grave Goods

The variety and richness of grave goods found in megalithic burials in India, especially in South India, underscore the meticulous efforts made to honor the dead. These findings not only reflect the cultural values and beliefs in the afterlife but also provide a comprehensive understanding of the material culture, economic activities, and technological advancements of megalithic societies.

Subsistence Pattern in Megalithic Culture

The megalithic culture in India, particularly in South India, demonstrates a diverse and advanced subsistence pattern. Contrary to the earlier belief that megalithic societies were nomadic pastoralists, archaeological evidence reveals a combination of agriculture, animal husbandry, hunting, fishing, and craft traditions. These features, along with megalithic monuments, point towards a sedentary lifestyle.

1. Agriculture

Agriculture formed the foundation of the megalithic economy. The megalithic builders introduced advanced agricultural methods, particularly tank irrigation, which revolutionized farming in South India.

Key features of megalithic agriculture:

- Crops: Cereals, millets, and pulses were widely grown. Evidence of charred grains of horse gram, green gram, ragi, and rice has been found at sites like Paiyampalli.

- Rice as Staple Food: Paddy husks and grains have been uncovered in graves across the region, indicating rice’s prominence as a staple crop. Sangam literature also attests to the importance of rice in South Indian diets.

- Implements: Findings of pestles and grinding stones, such as a granite grinding stone at Machad (Kerala), point to advanced food processing.

Megalithic sites were often located near irrigation tanks, streams, or other water sources. Graves were strategically placed on unproductive lands like rocky foothills, reserving fertile plains for agriculture. The placement of dolmens in fields, as seen in Uttaramerur (Tamil Nadu), likely symbolized ancestral spirits guarding and blessing agricultural lands.

2. Pastoralism

Animal husbandry was a significant aspect of the megalithic lifestyle. The remains of domesticated animals, such as cattle, sheep, goats, and pigs, indicate a continuation of earlier Neolithic traditions.

Key findings:

- Cattle Domestication: Cattle, including buffalo, were the most important domesticated animals, reflecting a focus on cattle pastoralism rather than sheep or goat rearing.

- Other Domesticated Animals: Pigs, dogs, fowl, horses, and donkeys were also reared, with evidence of small-scale pig farming and poultry farming.

Pastoralism supplemented agricultural activities, providing milk, meat, and other resources for the community.

3. Hunting and Fishing

Hunting played a crucial role in supplementing the diet of megalithic societies. Tools such as arrowheads, spears, javelins, and stone balls indicate hunting practices.

Evidence of hunting:

- Wild Fauna Remains: Skeletal remains of wild boar, hyena, deer, peacocks, nilgai, tiger, cheetah, sloth bear, and other species have been recovered, highlighting the variety of game hunted.

- Paintings and Figurines: Hunting scenes at Marayur and Attala (Kerala) depict animals like peacocks, stags, and antelopes, while scenes at Hire Benkal (Karnataka) show group dances and hunting activities.

Fishing was another significant activity, evidenced by:

- Terracotta Net Sinkers (Takalghat) and fish hooks (Khapa, Tangal, and Tamil Nadu graves).

- Fish Remains: Skeletal remains of fish at Yelleshwaram and other sites confirm the role of fishing in their diet.

4. Technology: Industries and Crafts in Megalithic Culture

The megalithic culture in India, particularly in South India, exhibited advanced technological capabilities and a rich tradition of specialized crafts. Archaeological evidence highlights various industrial and craft-based economic activities, including smithery, carpentry, pottery, lapidary (working with precious stones), basketry, and stone cutting.

(a) Metals and Metallurgy

Megalithic societies were proficient in the extraction, smelting, and utilization of metals such as iron, copper, gold, and silver. Evidence of smelting activities and metalworking at megalithic sites reflects the technological expertise of these communities.

Key Features of Metalworking:

- Smelting and Furnaces:

- Archaeological remains of crucibles, smelting furnaces, clay tuyeres, and metal slag (iron, copper) provide evidence of local metalworking.

- Sites like Paiyampalli (Karnataka) indicate the presence of iron-smelting activities.

- Ancient mines and mineral resources near megalithic sites, along with tools for smelting, suggest efficient exploitation of metallic resources.

- Fuel Sources:

- Pre-industrial smelters used charcoal, wood, dung, and paddy husk to achieve the required temperatures for smelting.

- Metal Implements:

- Iron implements include axes, ploughshares, hoes, sickles, and spades, reflecting their agricultural focus.

- Copper and bronze were primarily used for vessels, bowls, and ornaments.

- Gold ornaments and silver artefacts were rare but indicate a degree of metallurgical sophistication.

- Metallurgical techniques included casting, hammering, and alloying. Copper and bronze objects were often cast in moulds or hammered into shape.

Iron and Its Widespread Use

Iron was the most extensively utilized metal, dominating the artefacts found at megalithic sites. The large variety of iron objects reveals its importance in daily life and ritualistic practices.

Examples of Iron Objects:

- Utensils: Everyday tools for cooking and domestic use.

- Weapons: Arrowheads, spearheads, swords, and knives reflect the need for hunting and defense.

- Carpentry Tools: Axes, chisels, and adzes showcase the importance of woodworking.

- Agricultural Implements: Sickles, hoes, and ploughshares demonstrate the emphasis on farming as a primary occupation.

The abundance of iron tools for agriculture underscores the role of farming in the megalithic economy.

Copper, Bronze, Gold, and Silver

- Copper and Bronze:

- Copper artefacts, such as vessels and ornaments, were widespread.

- Bronze artefacts, though less common, were found at sites like Adichannallur and Nilgiris, which appear to be exceptions in the broader usage pattern.

- Gold and Silver:

- Gold ornaments, including bangles, necklaces, and earrings, indicate metallurgical sophistication.

- Silver was less commonly used, reflecting its scarcity.

- Metallurgical Techniques:

- Copper and bronze objects were either cast in moulds or hammered into shape.

- Alloying techniques were employed to enhance the quality and durability of metal artefacts.

(b) Woodcraft / Carpentry

The megalithic culture in India demonstrates a well-developed tradition of woodcraft and carpentry. Archaeological and botanical evidence points to the extensive use of wood for construction, tools, and daily life.

Key Features of Woodcraft:

- Tool-Kit for Woodworking:

- Tools like axes, chisels, wedges, adzes, anvils, borers, and hammer stones were central to woodworking activities.

- These tools indicate advanced skills in wood dressing and carpentry.

- Use of Wood in Agriculture:

- The use of wooden ploughs for cultivation, particularly in black cotton soil areas, was prevalent and continues even today.

- Construction Materials:

- Wood was used extensively for hut construction, with thatched or reed roofs supported by wooden posts.

- Evidence of timber constructions, such as postholes, has been found at sites like Brahmagiri and Maski.

- Advanced Wooden Architecture:

- Wooden architecture involved dressing of wood and creating mortice holes for interlocking or tenon joints.

- This reflects an advanced understanding of structural integrity and design.

- Known Plant Species:

- Botanical evidence shows knowledge of species like Acacia, Pinus, Brassica, Stellaria, Teak, and Satinwood, which were used for construction and other purposes.

The common occurrence of these woodworking tools and evidence of timber constructions suggest that carpentry was a significant craft within the megalithic society in India.

(c) Ceramics (Pottery)

Pottery played a vital role in the megalithic culture of India, serving both utilitarian and ceremonial purposes. The variety, craftsmanship, and designs of ceramics reflect the technological expertise and cultural preferences of the society.

Types of Ceramics:

- Black-and-Red Ware (BRW):

- Wheel-turned pottery predominantly used as tableware.

- Common forms: Bowls, dishes, lids, vases, basins, legged jars, and channel-spouted vessels.

- Utilitarian in nature, BRW was the hallmark of megalithic pottery.

- Burnished Black Ware:

- Features a shiny surface achieved through polishing.

- Prominent shapes: Elongated vases, tulip-shaped lids, goblets, spouted vessels, and ring-stands.

- Decorated with finials shaped like birds or animals, suggesting ceremonial usage.

- Red Ware:

- Utilitarian shapes such as legged vessels, ring-stands, and dough plates.

- Often used for storage and cooking.

- Micaceous Red Ware:

- Distinguished by pots with globular bodies and funnel-shaped mouths.

- Decorations include cording, appliqué, and painted designs.

- Grey Ware:

- Used for domestic purposes, although less common than other types.

- Russet-Coated Painted Ware (RCPW):

- The most attractive variety, featuring wavy lines and decorative motifs.

- Often bears post-firing graffiti, suggesting symbolic or ritualistic significance.

Production Techniques:

- Pottery was made from finely levigated clay, with minimal sand or gritty materials.

- Kilns at sites like Polakonda and Beltada Banahalli suggest organized production by professional potters.

- Pottery was fired in open kilns at low temperatures.

Functional and Ceremonial Uses:

- Pottery served as tableware for eating and drinking, and as cooking utensils.

- Decorated ceremonial wares, often featuring lids with bird or animal finials, highlight cultural and ritualistic practices.

(d) Miscellaneous Crafts and Trade in Megalithic Culture

The megalithic culture in India showcases a variety of crafts and industries beyond the agro-pastoral economy. These activities, ranging from bead making to long-distance trade, reflect the artistic, cultural, and economic complexity of megalithic societies.

1. Bead Making

Bead making was a prominent craft, evidenced by the discovery of beads and bead-making tools at sites like Mahurjhari and Kodumanal. Grave goods included finely etched carnelian beads, alongside beads crafted from a wide variety of materials.

Materials used in bead making:

- Semi-precious stones: Agate, carnelian, chalcedony, feldspar, crystal, garnet, jasper, serpentine, steatite, amethyst.

- Organic materials: Shell, horn, bone.

- Other materials: Gold, glass, faience, terracotta.

The diversity in materials and intricate designs indicates a high level of craftsmanship. Beads were not just for personal adornment but also held cultural and possibly trade significance.

2. Mat Weaving

The art of mat weaving is attested by impressions left on the bases of jars at sites like Managondanahalli and Nagarjunakonda. These impressions highlight the widespread use of mats, possibly for domestic and ceremonial purposes.

3. Stone Cutting

Stone cutting was a highly developed skill among megalithic communities. Evidence includes:

- Chisel impressions on a stone trough at Borgaon Khurd (Maharashtra).

- Rock-cut chamber tombs in Kerala and North Karnataka.

- Domestic stone artefacts like pestles, mortars, and saddle querns, found at various megalithic sites.

The ability to cut and shape stones reflects the technological advancements of the period, especially in the construction of tombs and tools.

4. Terracotta and Toys

Terracotta craft was an essential aspect of megalithic culture:

- Terracotta items: Discs, figurines, gamesmen, and miniature pottery vessels were often found in graves, particularly those of children, suggesting their use as toys.

- These artefacts reflect the societal emphasis on leisure and childhood.

5. Rock Art

The megalith builders were also creators of rock art. Paintings and engravings found in peninsular India illustrate hunting scenes, dances, and animals, offering insights into their daily lives and beliefs.

Examples:

- Burial stones with paintings and inscriptions mentioned in Sangam literature.

- Sites like Hire Benkal and Marayur reveal the artistic endeavors of megalithic people.

Trade and Exchange Networks

The megalithic culture in India was closely linked to trade and exchange networks, both regional and long-distance. These networks facilitated the movement of goods and ideas, enriching the megalithic economy.

1. Evidence of Trade:

- Grave goods: Items such as carnelian beads, bronze artefacts, and rouletted ware suggest non-local origins.

- Excavated materials: Finds like amphorae and other ceramics at sites like Arikamedu point to maritime trade connections.

2. Regional and Long-Distance Exchange:

- Inter-regional trade: Goods were exchanged across South India and the Gangetic region.

- Overseas trade: Graeco-Roman writings and Tamil texts mention maritime exchanges, including trade with the Mediterranean world.

- The demand for goods, such as copper, tin, and carnelian beads, drove these trade networks.

3. Factors Driving Trade:

- Regional variations in the availability of raw materials and finished goods.

- Demand for South Indian commodities like spices and gems in other parts of the subcontinent and overseas.

4. Evolution of Trade Networks:

- During the early Iron Age, trade was in its infancy but grew significantly by the 3rd century BCE.

- These networks connected unevenly developed communities through land and sea routes, with traders acting as intermediaries.

Social Organisation and Settlement Pattern in Megalithic Culture

The megalithic culture in India reflects a complex and diverse social organisation with distinct settlement patterns shaped by subsistence strategies, burial practices, and community dynamics. Evidence from anthropology and archaeology offers insights into the societal structure and living arrangements of megalithic communities.

1. Social Organisation

The megalithic society was not a homogeneous entity but displayed status differentiation and social stratification. This is evident from variations in burial types, grave goods, and settlement patterns.

Key Indicators of Social Stratification:

- Burial Types and Grave Goods:

- Elaborate burials, such as multi-chambered rock-cut tombs, contained rare artefacts made of bronze or gold, suggesting higher social status.

- Simpler urn burials with fewer artefacts reflected lower status.

- Ceramic Goods:

- High-quality and finely crafted ceramics in large and elaborate burials indicate a higher social standing of the buried individuals.

- Differentiation in Treatment at Death:

- The burial practices likely mirrored an individual’s social status during life, pointing to an organised society with established hierarchies.

Labour Organisation:

The construction of massive stone structures like cists, dolmens, and rubble mounds required organised manual labour, indicating the presence of a sizeable population and collaborative community efforts.

2. Settlement Pattern

Megalithic communities lived in villages and exhibited a gradual transition toward more structured and populous settlements, though they were slower in urban development compared to their contemporaries in the Gangetic Valley.

Characteristics of Settlements:

- Village Life:

- The megalithic people predominantly lived in villages comprising huts with thatched or reed roofs, supported by wooden posts.

- Evidence from sites like Brahmagiri and Maski, where postholes have been discovered, suggests timber construction for ordinary buildings.

- Population Size:

- Extensive burial grounds with multiple graves, sometimes containing remains of over 20 individuals, indicate a large population size.

3. Distribution of Settlements

The distribution of megalithic sites was influenced by environmental and economic factors, particularly the introduction of plough-based agriculture.

Key Observations:

- Locational Preferences:

- Settlements were concentrated in river valleys and basins, favouring black soil and red sandy-loamy soil zones, ideal for intensive plough cultivation.

- The preference for areas with annual rainfall between 600–1500 mm highlights the importance of rainfall for agriculture.

- Proximity to Water Sources:

- Most settlements were located near rivers, with burial sites typically within 10–20 km of major water resources, suggesting a reliance on water for both agriculture and ritual practices.

Impact of Agriculture:

The spread of plough cultivation during the megalithic period brought significant changes to settlement structure and distribution, fostering growth in both the size and number of settlements.

Religious Beliefs and Practices of the Megalithic Culture

The megalithic culture in India reveals complex religious beliefs and practices, primarily centered around the cult of the dead, animism, and rituals related to burial practices. These beliefs reflect the reverence for the deceased and a connection to ancestral worship, which continued to influence later cultures, as evidenced in Sangam literature.

1. Cult of the Dead

The elaborate architecture of graves and the inclusion of grave goods point to the deep veneration for the dead.

- The belief in an afterlife is evident, with the dead provided necessities like food, ornaments, and tools for use in the other world.

- Grave Goods:

- Items such as pottery, metal tools, and ornaments were buried with the deceased, reflecting the affection and respect of the living for their dead.

- Variations in grave goods and burial architecture suggest status differentiation.

- Large and labor-intensive burials indicate community participation, reflecting the importance of these rituals.

2. Animism

The belief in animism is demonstrated by evidence of animal sacrifices and symbolic representations:

- Animal Remains: Bones of domestic and wild animals, such as cattle, sheep, goats, and wolves, were found in graves. These animals may have been sacrificed for funeral feasts or to supply food for the deceased in the afterlife.

- Terracotta Figurines: Decorated animal figurines adorned with garlands and ornaments suggest their ritualistic significance.

3. Continuity of Beliefs in Sangam Literature

- Sangam literature, which overlaps with the late megalithic period, provides insights into burial practices, indicating the survival of earlier beliefs.

- Practices such as the erection of memorial stones (Virakal or Mastikal) highlight the association of stones with ancestral worship, a tradition that persisted in South India.

Polity in the Megalithic Culture

The megalithic culture in India reveals a distinct political organization centered around chiefdoms, characterized by tribal descent groups with shared resources and a system of redistribution. The variation in burial practices, grave goods, and monumental structures provides insights into the social hierarchy and political dynamics of the time.

1. Status Differentiation and Political Power

- Differences in the size of monuments and the nature of grave goods indicate status differentiation and ranking.

- Elaborate burials such as multi-chambered tombs, which required the mobilization of substantial collective labor, reflect the power and influence of the buried individual.

- The presence of urn burials for chieftains, even those of significant status, suggests a spectrum of burial practices that corresponded to the individual’s rank and resources.

2. Tribal Chiefdoms

- Chiefly Power:

- The society was organized around chiefdoms, where the chief (Perumakan, or “great son”) commanded personal, material, and cultural resources of the clan.

- Chiefs, their heirs, and warriors held privileged status, though the society lacked rigid class stratification.

- Flexible Hierarchy:

- The tribal power distribution was simple and kinship-based, with no clear aristocracy or stratified society, even by the mid-first millennium CE.

3. Coexistence of Small Chiefdoms

- The megalithic period witnessed the coexistence of numerous small chiefdoms.

- These chiefdoms often competed, with conflicts over resources leading to inter-clan and intra-clan raids.

- The competitive nature of these interactions fostered the emergence of larger chiefdoms by the turn of the Christian era.

4. Burial Practices and Chiefdoms

- Burial Monuments:

- The construction of elaborate sepulchral monuments, including multi-chambered rock-cut tombs and urn burials, highlights the respect and importance given to chieftains and warriors.

- Memorial Stones (Natukal):

- These were erected over the urn burials of great chiefs and warriors, emphasizing the emerging cult of heroism and ancestral worship.

- Cultural Continuity:

- References in Tamil heroic texts like Purananuru confirm that even prestigious chieftains received urn burials, reflecting a continued cultural practice.

5. Emergence of Bigger Chiefdoms

- Resource Control and Prestige Goods:

- The accumulation of prestige goods, ceramics, and other artefacts in graves suggests the growing resource control of larger chiefdoms.

- The interaction among clans fostered trade and cultural exchange, driving the growth of bigger chiefdoms.

- Armed Conflicts:

- Frequent armed confrontations and predatory subjugation of smaller clans led to the rise of more powerful chiefs.

- These conflicts not only contributed to the development of political power but also accounted for the construction of numerous burial monuments to honor fallen chiefs and warriors.

6. Transition to Early Historical Period

- The late phase of the megalithic period coincided with the early historical period, as reflected in archaeological findings and Sangam literature.

- This period marked the march toward larger chiefdoms and the evolution of socio-political structures:

- Chieftains began to consolidate power over resources and trade.

- Their influence grew beyond clan boundaries, setting the stage for more complex political entities.