January 25, 2026 12:31 pm

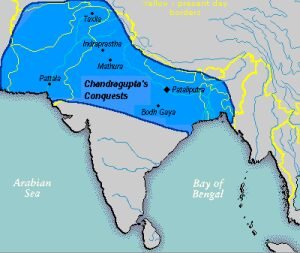

The Mauryan Empire, a geographically extensive Iron Age power, ruled over ancient India from 322 to 185 BCE. The Mauryan Empire’s foundation was established in 322 BCE when Chandragupta Maurya overthrew the last Nanda king. Seizing the opportunity presented by Alexander the Great’s withdrawal from India, Chandragupta quickly expanded his empire westward. By 316 BCE, he had conquered northwestern India, defeating the satraps left behind by Alexander’s forces. His territorial gains included additional regions to the west of the Indus River, following his defeat of Seleucus I, a Macedonian general from Alexander’s army, in 305 BCE.

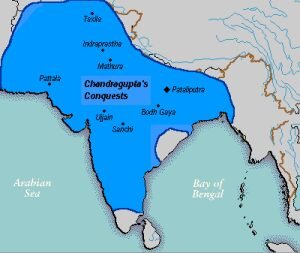

The Maurya Empire, under Chandragupta, grew into one of the world’s largest empires of its time. It stretched north to the Himalayas, east into Assam, west into Balochistan, and even into the Hindu Kush mountains in Afghanistan. Chandragupta and his successor Bindusara further expanded the empire into central and southern India, although they left some unexplored tribal and forested regions near Kalinga (modern-day Odisha) until Ashoka, Chandragupta’s grandson, later conquered these regions.

Despite its immense size, the Maurya Empire began to decline about 50 years after the death of Ashoka and eventually dissolved in 185 BCE, when the Sunga Dynasty was established in Magadha. At its height, the Maurya Empire’s population was estimated to be between 50 and 60 million people, making it one of the most populous empires of its time.

Sources of origin of the Mauryas

The origins of the Maurya dynasty have been depicted in various historical and religious texts. Different perspectives about their ancestry have been documented:

1. Kautilya’s (Chanakya) Arthashastra

One of the most significant contributions to the governance of the Maurya Empire was Kautilya’s Arthashastra, an ancient Indian treatise on statecraft, economic policy, and military strategy. Kautilya, also known as Chanakya or Vishnugupta, was Chandragupta’s chief advisor and played a pivotal role in his rise to power. The Arthashastra is a comprehensive manual that outlines the duties of a king, methods of governance, diplomacy, and warfare.

The text is divided into 15 sections, covering topics ranging from internal administration to foreign policy. Key features of the Arthashastra include:

- Statecraft: The Arthashastra defines the role of the king as an absolute ruler who must ensure the welfare of his subjects. It advocates for a centralized system of governance with the king at its helm, assisted by a council of ministers.

- Economic Policies: The treatise emphasizes state control over resources, including land, agriculture, and trade. It outlines taxation policies and methods for increasing revenue, including the state monopoly over certain goods like liquor and weapons.

- Military Strategy: Kautilya’s work is perhaps most famous for its detailed strategies for warfare. It discusses espionage, fortifications, and alliances. The concept of the Mandala theory, which states that neighboring states are enemies and distant states are allies, is central to its foreign policy framework.

- Justice and Law: The Arthashastra prescribes strict laws to maintain order and prevent corruption. It also discusses the importance of intelligence networks and spies in ensuring internal security.

- Diplomacy and Warfare: Kautilya outlines six strategies for dealing with neighboring states: appeasement (Sama), gifts (Dana), division (Bheda), punishment (Danda), illusion (Maya), and ignoring the enemy (Upeksha). These strategies formed the basis of Mauryan foreign policy.

2. Megasthenes’ Indica

Megasthenes, a Greek ambassador sent by Seleucus I to the Maurya court, wrote a detailed account of his experiences in India, called the Indica. Though the original work has not survived, fragments of the text have been preserved through later authors like Strabo, Arrian, and Pliny.

Megasthenes’ Indica provides a vivid description of India during Chandragupta’s reign, covering a wide range of subjects, including the geography of India, its flora and fauna, the customs of its people, and its political system. Notable elements include:

- Pataliputra: Megasthenes describes Pataliputra, the capital of the Mauryan Empire, as a massive city with 64 gates and 570 towers. The city was surrounded by a deep ditch and a wooden palisade, features that have been confirmed by archaeological excavations.

- Army and Society: Megasthenes recorded that Chandragupta’s army was composed of 600,000 infantry, 30,000 cavalry, and 9,000 war elephants. He observed that Indian society was divided into seven classes: philosophers, farmers, herdsmen, artisans, soldiers, overseers, and counselors. Megasthenes also noted that slavery did not exist in India, a claim that is not corroborated by other sources, such as the Arthashastra.

- Religious Practices: Megasthenes referred to the Indian worship of Dionysus and Herakles, names he used to describe Indian deities like Krishna and Shiva. He also described the ascetic practices of Indian philosophers, who bore similarities to Greek sophists.

3.Puranas

The Puranas contain king lists referring to the Maurya dynasty, though inconsistencies exist:

- One set of texts speaks of 13 Maurya kings who ruled for 137 years.

- Another set mentions only 9 kings.

4.Hemachandra’s Parishishtaparvan

This Jain text highlights Chandragupta’s connections to Jainism.

5.Vishakhadatta’s Mudrarakshasa

This 5th-century historical drama revolves around the clever machinations of Kautilya (Chanakya), a minister of Chandragupta, against Rakshasa, the minister of the former Nanda king. Although the story may not have a solid historical basis, it provides insights into the political dynamics of the time.

6.Buddhist Texts

Buddhist sources like the Mahavamsa and its 10th-century commentary, the Vamsatthapakasini, contain legends about Chandragupta and Ashoka. Other Buddhist texts, including the Dipavamsa, Mahavamsa, Ashokavadana, Divyavadana, and Vamsatthapaksini, provide information, much of it legendary, about Ashoka.

7.Additional Sources

- Milindapanha and Mahabhashya provide additional information about Chandragupta.

- The Tamil poet Mamulanar possibly references the southward expansion of the Mauryas in one of his poems.

- The Tibetan monk Taranatha’s History of Buddhism in India (17th century) includes legendary accounts of the Mauryas.

- Two notable works, Kautilya’s Arthashastra and Megasthenes’ Indica, hold special importance among textual sources.

- Archaeological remains from sites like Kumrahar and Bulandibagh (associated with Pataliputra, the Mauryan capital), as well as Taxila, Mathura, and Bhita, provide material evidence of the Mauryan period. Mauryan levels display increased diversity in artifacts and urban features.

- The Maurya period is also marked by Ashoka’s pillars and other architectural elements, which continue to stand as testaments to the empire’s grandeur.

- Sculptures and terracotta images from the Maurya period appear to reflect a popular urban culture.

- Coinage also emerged as a significant source during the Mauryan period. The most famous are punch-marked coins, mostly made of silver. These coins bore various symbols, such as crescents, arches, trees-in-railing, and peacocks. These symbols held cultural, royal, and religious significance. For instance, the tree-in-railing symbol is often associated with Buddha’s enlightenment, while other symbols represent the stupa.

Kautilya’s Arthashastra refers to different denominations of silver coins called panas and copper coins called mashakas. Punch-marked coins are a prominent archaeological source from the Mauryan period. For example, a silver punch-marked coin from the Mauryan empire features symbols of a wheel and an elephant, dating to the 3rd century BCE.

8. Archaeological and Numismatic Sources

Archaeological investigations have provided valuable insights into the Mauryan period, though reliable dates and extensive discoveries are somewhat limited. Several key sites and artifacts have been identified as being associated with the Maurya Empire, offering a glimpse into the architectural, administrative, and economic advancements of the time.

Key Archaeological Sites

- Kumrahar and Bulandibagh: These sites are closely associated with the Mauryan capital, Pataliputra (modern Patna). Pataliputra was renowned for its wooden architecture, especially its grand palaces, fortifications, and public buildings. Remains from these sites showcase the advanced urban planning and architectural prowess of the Mauryan era.

- Taxila: An important city during the Mauryan period, Taxila was a major center of learning and commerce. Excavations have revealed various levels of occupation, with Mauryan-era layers displaying significant urban development and artifacts.

- Mathura: Another key city in Mauryan times, Mathura played a role in both administrative and religious aspects of the empire. Mauryan-period layers have yielded terracotta figures and other items indicating the city’s importance.

- Bhita: This lesser-known site also contains Mauryan levels, with findings that include pottery, sculptures, and other artifacts indicative of the urban features and daily life during the Mauryan rule.

Artifacts and Architectural Elements

- Ashoka’s Pillars: One of the most iconic symbols of the Mauryan Empire, the pillars of Ashoka were erected across the subcontinent. These pillars, inscribed with Ashoka’s edicts promoting Dhamma (righteousness), serve as significant archaeological evidence of Ashoka’s governance and religious reforms. The Lion Capital of Ashoka, found atop some of these pillars, has become the national emblem of modern India.

- Sculptural Elements: The Mauryan period is known for its distinct art forms, including stone sculptures that blend indigenous and foreign styles. Sculptural elements found in various parts of the empire reflect the artistic achievements of the Mauryan era.

- Stone Inscriptions: Ashokan edicts, inscribed on rocks and pillars, provide direct evidence of the administrative and ethical policies of Ashoka. These inscriptions, written in Brahmi script, are key historical records detailing Ashoka’s governance and moral principles, including his promotion of non-violence and welfare policies.

Mauryan Coinage

Coins from the Mauryan period, particularly the silver punch-marked coins, are crucial for understanding the empire’s economy. These coins feature various symbols that held cultural, religious, and royal significance.

- Symbols on Coins:

- Wheel: A possible representation of the Dharma Chakra, symbolizing law, authority, and moral governance.

- Elephant: A symbol that may represent royal power, prosperity, or religious significance, as elephants were considered sacred animals in many Indian traditions.

- Significance of Coins: These punch-marked coins are important not just for their monetary value but also for the cultural and symbolic messages they carried. They offer insights into the Mauryan economy, which was largely agrarian but also involved trade, both internal and with foreign regions. The Arthashastra also mentions various denominations of silver and copper coins, such as panas and mashakas, reflecting a sophisticated monetary system during the Mauryan era.

Expansion of the Mauryan State

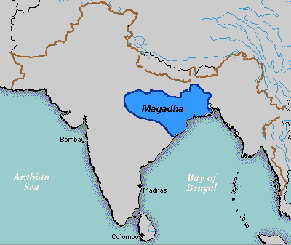

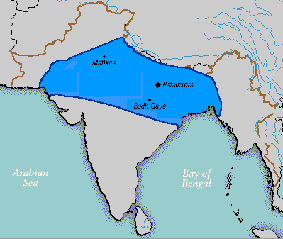

The Maurya state emerged from Magadha, a powerful kingdom in the 5th century BCE, under the Nanda Empire at its greatest extent during 323 BCE. After defeating the Nandas, Chandragupta Maurya founded the Maurya Empire in 320 BCE. The empire expanded further under Bindusara and Ashoka, who extended the empire’s southern and western borders. The empire’s extent is illustrated through maps showing its growth, including the acquisition of territory following Chandragupta’s victory over Seleucus in 305 BCE.

Chandragupta Maurya (320 B.C. – 298 B.C.)

Sources and his early life:

Chandragupta’s ancestry remains a subject of speculation, with his background pieced together from classical Sanskrit, Buddhist, and Greek sources.

- Greek and Latin Sources: Classical Greek and Latin writers like Plutarch refer to Chandragupta by the names Sandracottos or Andracottus. Plutarch reports that Chandragupta met Alexander the Great near Takshasila and held a negative view of the Nanda Empire.

- Roman Historian Justin: In his accounts, Justin describes Chandragupta’s humble beginnings and how he led an uprising against the Nanda king.

Chandragupta’s historical encounter with the Nanda king is said to have taken place around 326 BCE, suggesting his birth around 340 BCE.

- Sanskrit Sources: Puranas, Mudrarakshasa, and Mahavamshatika also reference Chandragupta’s conflict with the Nandas. The tradition holds that Kautilya (Chanakya) aided Chandragupta in overthrowing the Nandas.

Rise of Chandragupta Maurya and Foundation of the Maurya Dynasty

Chandragupta’s rise coincided with Alexander’s invasion of the north-western parts of the Indian subcontinent. In the years following Alexander’s death, a power vacuum emerged as the governors left behind by the Macedonian ruler either retreated or were assassinated. Chandragupta seized the opportunity and quickly subdued the Greek garrisons in the northwest, establishing himself first in Punjab and later in Magadha. By 321 BCE, Chandragupta had consolidated his power and assumed the throne of Magadha.

Military Achievements of Chandragupta’s Empire

Megasthenes, who later served as an ambassador in Chandragupta’s court, recorded that Chandragupta’s army consisted of around 400,000 soldiers. Pliny’s accounts suggest that the army had even larger numbers—600,000 infantry, 30,000 cavalry, and 9,000 war elephants—demonstrating the empire’s military might.

1. Conflict with Seleucus I

One of Chandragupta’s major military achievements was his conflict with Seleucus I, a successor to Alexander the Great’s empire. In 305 BCE, Chandragupta defeated Seleucus, gaining territories in eastern Afghanistan, Baluchistan, and regions west of the Indus River. This victory was further cemented by a marriage alliance, with Chandragupta reportedly marrying Seleucus’s daughter. The peace treaty resulted in the exchange of 500 war elephants, solidifying Chandragupta’s position in the region. Seleucus also dispatched the Greek ambassador Megasthenes to Chandragupta’s court, where he lived for many years, documenting the empire’s wealth, military strength, and governance.

Greek sources like Strabo also noted the existence of dedicated departments for foreign nationals in the Mauryan administration, further highlighting the diplomatic exchanges between the Mauryan rulers and Hellenistic kingdoms.

2. Conquests in Southern India

Chandragupta’s expansion into the southern regions of India is referenced by multiple sources. Tamil literature, particularly a poem by the Sangam poet Mamulanar, makes a possible reference to Chandragupta’s conquest in the south. These conquests extended the Mauryan influence into the Deccan Plateau, and the Mauryas are said to have had an alliance with the southern kingdom of Koshar. Furthermore, Deccani troops are noted to have formed part of Chandragupta’s military.

Another significant reference to Chandragupta’s southern expansion comes from a Junagadh Rock Inscription from the second century CE, which mentions a governor named Pushyagupta, appointed by Chandragupta, who constructed the famous Sudarshana Lake. This suggests that the Maurya influence extended to the extreme west of India, including regions such as Kathiawar (modern-day Gujarat).

The conquests and consolidation of Chandragupta Maurya helped form a vast and diverse empire. By the end of his rule, the Mauryan Empire included most of the Indian subcontinent, barring a few unexplored forested and tribal areas, especially in the south.

Relation Between Chandragupta, Jainism, and Karnataka

Towards the end of his life, Chandragupta is said to have embraced Jainism. According to Jain tradition, Chandragupta renounced his throne and accompanied the Jain monk Bhadrabahu to Karnataka, where he is said to have performed the Jain practice of Sallekhana, or voluntary death by fasting. Several inscriptions and literary works, including the Brihatkathakosha of Harishena (10th century CE) and Rajavali-kathe, mention this event. The latter, a 19th-century text, notes that Chandragupta spent his last days in the Shravana Belgola hills of Karnataka, where several locations bear his name.

Chandragupta’s adoption of Jainism and his migration to the south illustrate the widespread influence of Mauryan culture and politics across India, as well as the emperor’s personal spiritual transformation.

Administration Under Chandragupta

The Mauryan Empire was known for its highly centralized administrative structure, which was heavily influenced by Kautilya’s Arthashastra. The empire was divided into provinces, each governed by a royal family member or a high-ranking official known as a Rashtriya. The provinces were further divided into districts, administered by a Sthanik, and villages, which were overseen by a Gopa.

The civic administration of large cities, including Pataliputra, was particularly efficient. The city was divided into sectors, each governed by a Sthanik, and junior officials, known as Gopas, supervised groups of families. The Nagrika was responsible for overseeing the entire city. There was a regular system of census-taking to keep track of the population.

The spy network was another significant aspect of Chandragupta’s administration. Kautilya placed great emphasis on espionage and internal surveillance, with spies tasked with monitoring officials and ensuring the king was informed about the smallest details of his empire.

Decline of Chandragupta’s Reign

Chandragupta Maurya ruled for approximately 24 years before abdicating the throne in favor of his son, Bindusara, around 297 BCE. Following his abdication, Chandragupta migrated south to Karnataka, where he embraced Jainism and spent the remainder of his life practicing asceticism. He is said to have died after performing Sallekhana, a ritual fasting unto death, under the guidance of Bhadrabahu.

Bindusara (298 B.C to 272 B.C)

Chandragupta’s son Bindusara succeeded him around 297 BCE. Bindusara, also known as Amitraghata (slayer of enemies), continued the policies of territorial expansion, extending the empire further into southern India. Buddhist sources remain relatively silent about Bindusara, though Jain works and later Tibetan sources like Taranatha’s History of Buddhism in India mention his warlike activities.

Bindusara is said to have subjugated sixteen cities and reduced the territory between the eastern and western seas. Tamil poets from the Sangam literature describe the Mauryan chariots thundering across the Deccan, which likely refers to Bindusara’s reign.

Notably, Kalinga (modern Odisha) did not form part of Bindusara’s empire, and it was later conquered by his son Ashoka, who served as the viceroy of Ujjaini during Bindusara’s reign. Bindusara also had diplomatic relations with Antiochus I of Syria, who sent an ambassador named Deimachus to his court. Pliny the Elder reports that Bindusara asked Antiochus to send him sweet wine, dried figs, and a sophist (a philosopher specializing in debate), though the latter request was denied, as Greek laws prohibited the sale of philosophers.

Foreign Relations of Bindusara- Mauryan Diplomacy

One of the distinguishing features of Bindusara’s reign is the Mauryan Empire’s continued diplomatic relations with Hellenistic kingdoms. The Greek sources, such as Strabo, mention that Antiochus I, the king of Syria, sent an ambassador named Deimachus to Bindusara’s court. Similarly, Ptolemy II Philadelphus of Egypt sent an ambassador named Dionysius to Bindusara. These diplomatic exchanges reflect the Maurya Empire’s significant standing in the ancient world, particularly with its neighbors in the west.

There is an interesting anecdote recorded by Pliny the Elder, which describes how Bindusara requested Antiochus to send him sweet wine, dried figs, and a sophist (a philosopher specialized in debate). While Antiochus agreed to send the wine and figs, he refused to send a sophist, as Greek law forbade the sale of such intellectuals.

Issues faced by Bindusara

Rebellions in Taxila

One of the most notable challenges Bindusara faced during his reign was a series of rebellions in Taxila, a major provincial capital in the northwestern region of the empire. According to historical accounts, the first revolt was due to the maladministration of his son Suseema, who was the governor of the province. Although the reasons behind the second revolt remain unclear, Bindusara was unable to suppress it during his lifetime. The revolt was eventually quelled by his younger son, Ashoka, after Bindusara’s death in 272 BCE.

Succession Crisis

After Bindusara’s death in 272 BCE, there was a struggle for succession among his sons, which lasted for about four years. Ultimately, Ashoka, one of Bindusara’s younger sons, emerged victorious and ascended the throne around 268 BCE. The Rajavalikatha, a Jain text, mentions that Bindusara’s original name was Simhasena, though he is more commonly known by his title of Amitraghata (slayer of enemies).

[…] Mauryan Empire: Foundation and Expansion […]

[…] Mauryan Empire: Foundation and Expansion […]

[…] Mauryan Empire: Foundation and Expansion […]

[…] Mauryan Empire: Foundation and Expansion […]

[…] Mauryan Empire: Foundation and Expansion […]

[…] Mauryan Empire: Foundation and Expansion […]

[…] Mauryan Empire: Foundation and Expansion […]