January 25, 2026 1:54 am

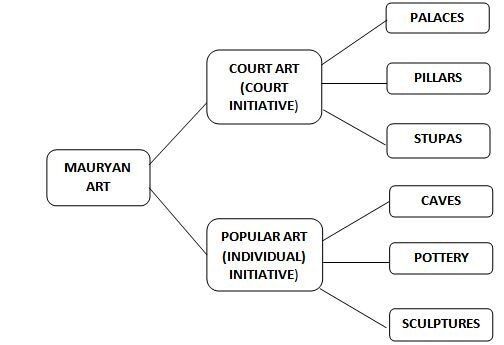

The Mauryan Empire (circa 322–185 BCE) marked a significant turning point in the development of Mauryan Art, architecture, and sculpture in India. After a long period of decline following the Indus Valley Civilization, the Mauryan Art period witnessed the revival and flourishing of monumental stone architecture. This era saw a remarkable transition from wood to stone as the primary medium, showcasing the innovative nature of Mauryan Art, and a blossoming of sculptural traditions that would leave a lasting legacy in Indian art history. Mauryan Art also reflects a convergence of political ideology, religious patronage, and artistic expression, making it a defining feature of this historical period.

Revival of Stone Sculpture and Architecture During the Mauryan Period

During the Mauryan period, there was a significant revival of monumental stone sculpture and architecture, marking a return to the craftsmanship that had not been seen since the Indus Valley Civilization. This period is often considered the pinnacle of Mauryan art, reflecting the grandeur and vision of the Mauryan rulers. The Mauryan Empire was the first large-scale political structure in India, and its rise brought about a surge in urbanization, wealth concentration, and centralized political authority. These factors collectively contributed to the creation of monumental structures that encapsulated the power and ideals of the Mauryan rulers, particularly under the reign of Emperor Ashoka, who is closely associated with the flowering of Mauryan art.

One of the most remarkable developments in Mauryan art was the transition from wood to stone as the primary medium for architecture and sculpture. Earlier traditions primarily relied on wood, but the Mauryan period saw the dominance of stone, establishing a legacy in Indian art and architecture. The discovery of monumental architecture at Dholavira from the Harappan period shows that stone construction existed in ancient India. However, after the decline of the Indus Valley Civilization, monumental stonework did not reappear until the revival of Mauryan art, which reintroduced and redefined the use of stone for large-scale projects.

The emergence of monumental architecture during the Mauryan period is intrinsically linked to the political and cultural complexities of the era. As the Mauryan Empire consolidated power, urban elites gained wealth and resources, which they directed toward sponsoring architectural marvels. Furthermore, the institutionalization of Buddhist and Jain religious practices, particularly under Ashoka, provided additional motivation for creating iconic religious monuments. Structures like stupas and intricately carved pillars are outstanding examples of Mauryan art, showcasing the empire’s dedication to blending political authority with religious and artistic expression.

Court Art: The Patronage of the Mauryan Kings

The art and architecture of the Mauryan period were profoundly influenced by court patronage, with the Mauryan kings playing a pivotal role in their development. Among these rulers, Emperor Ashoka stands out as the most significant patron of Mauryan art. The surviving examples of Mauryan art and architecture—such as the iconic Ashokan pillars, stupas, and royal palaces—are enduring testaments to the impact of royal sponsorship during this era. These creations not only symbolize the political authority of the Mauryan dynasty but also reflect their commitment to fostering religious and artistic traditions that would leave a lasting legacy in Indian history.

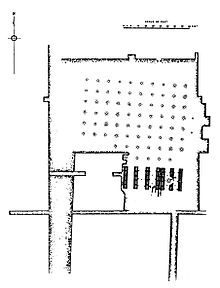

2.1 The Mauryan Palace at Kumhrar

One of the most important examples of Mauryan court art is the Mauryan palace at Kumhrar, near Patna, believed to have been the royal palace of Chandragupta Maurya. The 80-pillared hall discovered at this site is a significant architectural achievement of the period. The hall contained 72 pillars arranged in a chessboard pattern, along with additional brick structures, indicating the scale and grandeur of the palace. The pillars were made of Chunar sandstone, a type of fine-grained buff-colored stone, known for its polished surface.

Although no complete pillars have been found, it is evident from the remains that the palace combined both stone and wood. The pillars, though made of the same material as the famous Ashokan pillars, were thinner and shorter. Burnt wood and ash were discovered at the site, suggesting that the palace was destroyed by fire at some point. The floor and roof of the palace were made of wood, and seven wooden platforms made of sal wood were excavated.

The structure of the 80-pillared hall has been compared to Darius’ Hall of Public Audience at Persepolis in Iran, but the Mauryan structure was far less elaborate than its Persian counterpart. Despite this, the palace at Kumhrar demonstrates the Mauryans’ ability to combine local architectural traditions with foreign influences, particularly from Persian and Achaemenid art.

2.2 Fortifications of Pataliputra

Pataliputra, the capital of the Mauryan Empire, was a grand city that served as a hub of political and military power. According to Megasthenes, the Greek ambassador to the Mauryan court, Pataliputra was a parallelogram-shaped city, measuring nine miles by one and a half miles, surrounded by a large ditch that was used both for defense and to manage the city’s water supply. The city was further protected by a timber palisade, which had loop holes for archers and was reinforced by 570 towers and 64 gateways.

Sections of the wooden fortifications at Bulandibagh, near Patna, provide additional insight into the construction of the city’s defenses. The wooden walls were covered with mud to a certain height, and the remains of a wooden drain have also been found, showcasing the city’s advanced water management system. Additionally, the discovery of a large spoked wooden chariot wheel with an iron rim at Bulandibagh highlights the Mauryan advancements in engineering and technology.

3. Ashokan Pillars: The Monumental Symbol of Power and Dhamma

One of the most enduring legacies of the Mauryan period is the construction of the Ashokan pillars. These free-standing pillars, erected across the northern Indian subcontinent, were inscribed with edicts that promoted Ashoka’s policy of Dhamma (moral law). The pillars not only served as a symbol of Ashoka’s authority, but also as a way to disseminate his ethical and religious teachings throughout the empire.

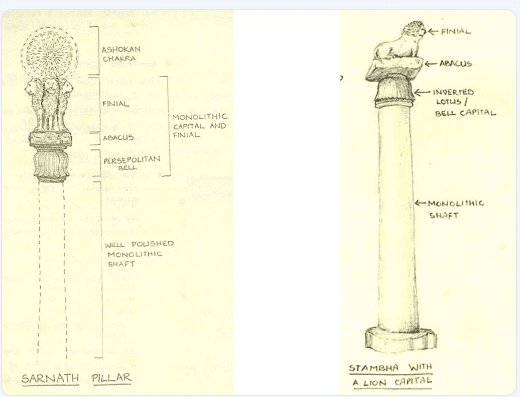

3.1 Structure and Construction of Ashokan Pillars

Each pillar consists of three main sections:

- The Shaft: The main body of the pillar, made from a single piece of stone, is smooth and circular in shape. It tapers slightly upwards and is unornamented.

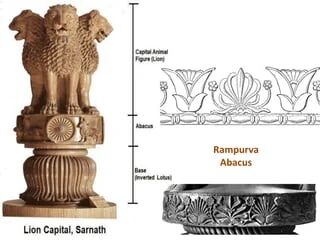

- The Capital: The capital is the topmost section of the pillar, often carved in the shape of an animal, such as a lion, bull, or elephant. The Sarnath capital, for instance, features four lions seated back to back, and it is now the national emblem of India.

- The Abacus: The abacus is a platform located between the shaft and the capital. It is often decorated with floral designs or geometrical patterns, and in some cases, animals such as geese or bulls are depicted.

3.2 Symbolism and Distribution of Ashokan Pillars

The Ashokan pillars are thought to symbolize the axis mundi, or the axis of the world, linking heaven and earth. The animal capitals at the top of the pillars also carry symbolic meanings related to Buddhism and Ashoka’s Dhamma. The lion, for example, is often interpreted as a symbol of the Buddha, who is sometimes referred to as the Sakya-simha (lion of the Sakyas). The bull is a fertility symbol and is associated with the Rishabha, the asterism under which the Buddha was born.

The wheel (dharmachakra) is another important motif found on many Ashokan pillars, particularly at Sarnath and Sanchi. The wheel symbolizes the Buddha’s first sermon and the spread of his teachings. The lotus, another common symbol, represents purity and spiritual enlightenment.

The distribution of Ashokan pillars is vast, with examples found in Bihar (Kolhua, Lauriya Areraj, Lauriya Nandangarh, Rampurva), Delhi (Topra), Allahabad, Sarnath, Sanchi, Lumbini, Nigalisagar, Basarh, and Kosam.

3.3 Persian Influence on the Ashokan Pillars

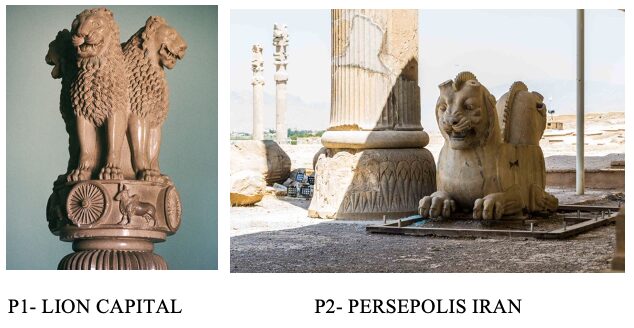

There is a clear Persian influence in the design of the Ashokan pillars, particularly in the polished stone and the use of animal capitals. The Achaemenid rulers of Persia also constructed monumental pillars with inscriptions to proclaim their victories and policies. It is possible that Ashoka adopted this practice after coming into contact with Persian traditions, as Darius I had similarly inscribed his proclamations on stone pillars.

However, there are significant differences between Persian pillars and Mauryan pillars. The Achaemenid pillars were often fluted, while Ashokan pillars are smooth and unornamented. Additionally, the Achaemenid capitals often featured two animals seated back to back, while the Mauryan capitals are more varied and include animals such as elephants and lions.

4. Mauryan Stupas: A New Architectural Form

One of the most important contributions of the Mauryan period to Indian architecture was the construction of stupas. Stupas are large, dome-shaped structures that originally served as funerary mounds, but by the Mauryan period, they had become symbolic of Buddhist religious practices. Ashoka is credited with constructing or enlarging 84,000 stupas across his empire, marking important sites related to the Buddha’s life and spreading the Buddhist faith.

4.1 Structure of Mauryan Stupas

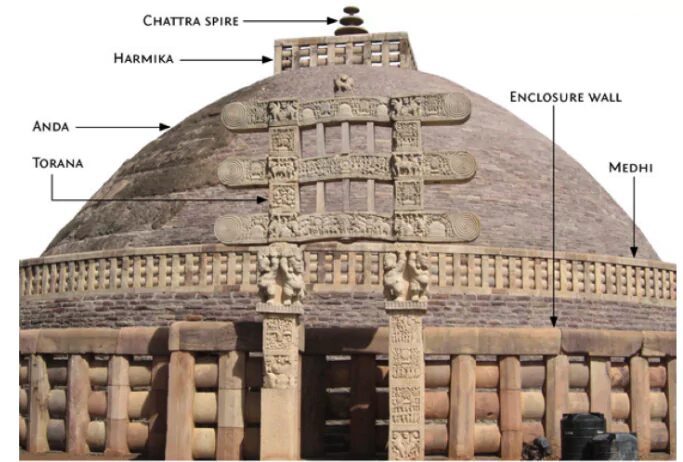

The basic structure of a stupa consists of several key architectural elements:

- Anda: The hemispherical dome that forms the main body of the stupa, symbolizing the universe.

- Harmika: A square railing at the top of the anda, representing the throne of the Buddha.

- Chhatra: An umbrella-like structure placed on top of the harmika, symbolizing protection.

- Vedika: A stone railing surrounding the stupa, used by devotees to circumambulate the structure.

- Torana: The gateway to the stupa, often elaborately carved with scenes from the Buddha’s life and Jataka stories.

4.2 Sanchi Stupa

The Great Stupa at Sanchi, one of the most famous stupas in India, was originally built by Ashoka. It served as a nucleus for Buddhist worship and was later enlarged during the Sunga period. The stupa at Sanchi features a brick core covered with stone and is surrounded by a stone railing. The toranas, or gateways, were added later and are richly carved with scenes from the life of the Buddha and Buddhist cosmology.

The Sanchi stupa exemplifies the architectural advancements of the Mauryan period and the growing importance of stupas as symbols of the Buddhist faith.

5. Mauryan Rock-Cut Architecture: The Barabar and Nagarjuni Caves

The rock-cut architecture of the Mauryan period represents one of the most innovative developments in Indian architecture during this time. The creation of rock-cut caves as places of worship, meditation, and living quarters for ascetics marked a significant departure from earlier architectural practices that primarily used wood and brick. The Barabar and Nagarjuni caves in present-day Bihar are the most prominent examples of Mauryan rock-cut architecture, and they demonstrate the high level of skill and craftsmanship achieved during this period.

5.1 The Barabar Caves

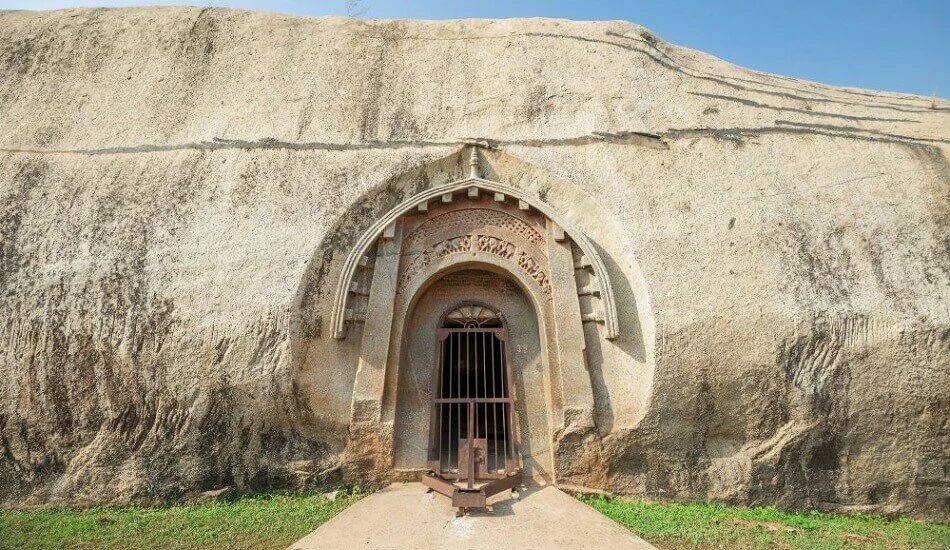

The Barabar caves, located in the Barabar hills north of Gaya, are some of the oldest surviving examples of rock-cut architecture in India. These caves were commissioned by Ashoka for the Ajivika sect, a religious group that existed alongside Buddhism and Jainism in ancient India. The Barabar caves are notable for their polished interiors, which reflect the agate burnishing technique used in Mauryan pillars, and their simple yet elegant design.

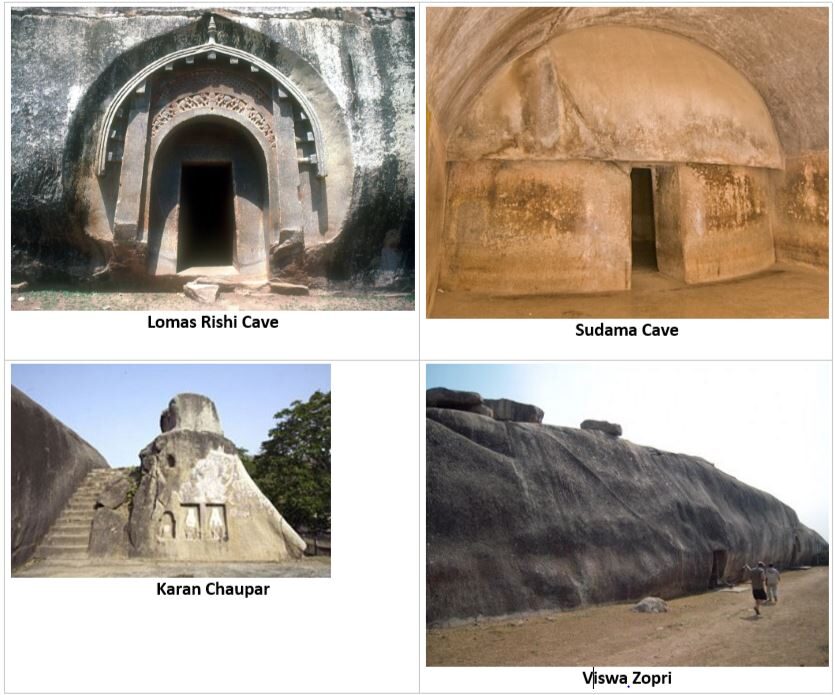

There are four primary caves in the Barabar hills:

- Lomas Rishi Cave

- Sudama Cave

- Karna Chaupar Cave

- Visva Zopri Cave

The Lomas Rishi Cave is perhaps the most famous of the Barabar caves, with its arched entrance that mimics the wooden structures of earlier times. This cave has a horseshoe-shaped façade, and the entrance is decorated with intricate carvings that depict elephants, lotus motifs, and the beginnings of what would become the chaitya arch—a feature that would later be fully developed in Buddhist rock-cut architecture.

The Sudama Cave has a simple plan but features a highly polished interior, which was likely used as a meditation hall by the Ajivikas. The precision with which the caves were carved out of solid rock, combined with the smoothness of their walls, shows the Mauryan craftsmen’s mastery of stone cutting and finishing techniques.

5.2 The Nagarjuni Caves

The Nagarjuni caves, located in the Nagarjuni hills close to the Barabar caves, are also attributed to the Mauryan period, and were commissioned by Dasharatha Maurya, Ashoka’s grandson. These caves are larger than the Barabar caves and feature similar polished interiors. Like the Barabar caves, the Nagarjuni caves were dedicated to the Ajivika sect and served as monastic retreats.

The Nagarjuni caves include:

- Gopika Cave

- Vadathika Cave

- Vapiyaka Cave

Each of these caves follows a similar design to the Barabar caves, with simple rectangular chambers and polished stone surfaces. The rock-cut architecture of the Barabar and Nagarjuni caves set the foundation for the more elaborate Buddhist chaitya halls and vihara caves that would be developed in later periods, particularly during the Kushan and Gupta dynasties.

5.3 Symbolism and Function of the Caves

The Barabar and Nagarjuni caves were primarily used by ascetic monks, particularly those belonging to the Ajivika sect, who practiced a form of extreme asceticism. The caves served as living quarters, meditation halls, and retreats, offering the monks an isolated space away from the bustling urban centers of the Mauryan Empire.

The smooth, highly polished interiors of the caves reflect the Mauryan emphasis on craftsmanship and the importance of creating spaces that were aesthetically pleasing yet functional for spiritual practice. The simplicity of the caves’ design aligns with the ascetic ideals of the monks who lived there, emphasizing the renunciation of worldly pleasures and the pursuit of spiritual enlightenment.

The archway designs seen in the Lomas Rishi Cave are some of the earliest examples of the chaitya arch, a form that would later become a defining feature of Buddhist architecture. This shows that the rock-cut architecture of the Mauryan period not only served immediate religious purposes but also laid the groundwork for future architectural innovations.

6. The Transition from Wood to Stone in Mauryan Architecture

One of the most significant developments in Mauryan architecture was the transition from wood to stone as the primary building material for monumental structures. Prior to the Mauryan period, Indian architecture primarily used wood, brick, and other perishable materials, which limited the scale and permanence of buildings. The Mauryan period saw the first widespread use of stone in Indian architecture, and this transition had a lasting impact on the development of Indian architectural styles.

6.1 Early Wooden Structures and Their Influence on Stone Architecture

Before the Mauryan Empire, most monumental structures in India were made from wood. This tradition continued into the early Mauryan period, as evidenced by the wooden fortifications of Pataliputra and other Mauryan cities. Megasthenes described Pataliputra as a city fortified with timber, with large wooden walls and towers. Archaeological excavations at Bulandibagh in Patna have uncovered remnants of these wooden fortifications, along with a large wooden drain that highlights the city’s advanced water management system.

Although much of the early Mauryan architecture was made of wood, the empire soon began to transition toward the use of stone, especially for royal buildings and religious monuments. The architecture of the Mauryan palace at Kumhrar in Pataliputra shows this transition, with stone pillars supporting wooden roofs and floors.

6.2 The Role of Persian and Achaemenid Influence

The transition from wood to stone in Mauryan architecture may have been influenced by Persian and Achaemenid architecture, particularly the monumental stone buildings at Persepolis and Susa. Darius I and other Achaemenid rulers built stone palaces and audience halls that utilized large stone columns and intricate stone reliefs. The Mauryan pillars, with their polished surfaces and animal capitals, show clear parallels to the Achaemenid columns of Persepolis, though the Mauryan pillars were more simplified in design.

However, despite these foreign influences, Mauryan architecture developed its own distinct style, combining local traditions with imported ideas. The Mauryan use of stone was particularly innovative in the context of Indian architectural history, as it marked the beginning of a long tradition of stone building that would continue to evolve in the centuries that followed.

7.3 The Influence of Stone Architecture on Later Indian Dynasties

The use of stone in Mauryan architecture laid the foundation for the architectural developments of later Indian dynasties, particularly the Gupta and Kushan periods. The construction of stone temples, chaitya halls, and stupas became more common in the post-Mauryan period, as Indian builders mastered the art of stone carving and began to create more elaborate and permanent structures.

The influence of Mauryan stone architecture can be seen in the stupas and pillars of later periods, such as the stupa at Bharhut and the Great Stupa at Sanchi. The Buddhist chaitya halls at Ajanta and Ellora, with their finely carved stone facades and intricate interior designs, also reflect the lasting impact of the Mauryan tradition of rock-cut architecture.

8. Metalwork in the Mauryan Period: Artistic and Technological Achievements

The Mauryan period was also notable for its achievements in metalwork, particularly the use of iron and bronze in the production of tools, weapons, and art objects. While stone architecture and sculpture have survived as the most prominent legacies of the Mauryan period, metalwork was equally important in shaping the technological and artistic achievements of the empire.

8.2 Bronze and Copper Artifacts

In addition to iron, bronze and copper were widely used during the Mauryan period to create artistic objects and household items. Bronze figurines, vessels, and tools have been found at several Mauryan sites, indicating the high level of craftsmanship in metalworking during this time.

One of the most famous examples of Mauryan metalwork is the Didarganj Yakshi, a highly polished stone sculpture that was likely once adorned with bronze or copper ornaments. While the Yakshi itself is made of stone, it reflects the artistic style of the time, which often combined stone sculpture with metal adornments to create a striking visual effect.

8.3 Influence on Later Metalwork Traditions

The metalworking techniques developed during the Mauryan period had a lasting influence on Indian art and technology. The use of iron, bronze, and copper continued to evolve in later periods, particularly during the Gupta and Medieval periods, when Indian metalworkers achieved new heights in the production of bronze statues, iron weapons, and ornamental metalwork.

The tradition of casting bronze sculptures, which would reach its peak during the Chola dynasty in South India, can be traced back to the innovations in metalwork during the Mauryan period. The combination of technical skill and aesthetic refinement that characterized Mauryan metalwork laid the foundation for the development of Indian metallurgy and metal sculpture in later centuries.

9. Iron Technology and the Mauryan Empire

The Mauryan Empire benefited from advances in iron technology, which played a crucial role in the development of the empire’s infrastructure, including the construction of fortifications, roads, and bridges. Iron tools were used extensively in agriculture, helping to increase food production and support the growing urban population. Iron weapons gave the Mauryan military a strategic advantage, allowing it to expand and maintain control over a vast territory.

The development of iron metallurgy also influenced the production of iron art objects during the Mauryan period. Iron pillars and railings were used in some of the early Buddhist structures, such as stupas and monasteries. These iron elements were often intricately designed and served both functional and decorative purposes.

10. Mauryan Sculpture: Yaksha and Yakshi Figures

Mauryan sculpture includes both courtly and folk art, with a rich tradition of stone and terracotta sculptures. One of the most prominent forms of Mauryan sculpture is the representation of Yaksha and Yakshi figures, deities associated with fertility and nature.

10.1 The Yakshi of Didarganj

One of the finest examples of Mauryan sculpture is the Yakshi figure from Didarganj, located in Patna. This statue, made of Chunar sandstone, is famous for its highly polished surface and the naturalistic depiction of the female form. The Yakshi figure represents a deity of fertility and is adorned with elaborate jewelry, highlighting the Mauryan artisans’ mastery over stone carving.

10.2 Yaksha Figures

Yaksha statues have been found at several Mauryan sites, including Mathura and Patna. These figures, often depicted as muscular male deities, were worshipped as guardians of nature and wealth. The Yaksha statues are among the earliest examples of Indian sculptural art, and their influence can be seen in later Buddhist and Hindu iconography.

11. Folk and Popular Art in the Mauryan Period

While the courtly art of the Mauryan period is known for its grandeur and direct connection to the royal patronage of figures like Ashoka, there was also a flourishing of folk and popular art, which provides a glimpse into the lives, beliefs, and artistic expressions of ordinary people during this time. Unlike court art, which was primarily intended to convey the power and authority of the state, folk art was closely tied to daily life, local traditions, and ritual practices.

The folk art of the Mauryan period includes terracotta figurines, stone sculptures, ring stones, and disc stones, all of which demonstrate a vibrant, localized artistic tradition that existed alongside the more formal, state-sponsored projects of the Mauryan kings. These pieces are often smaller and more personal in nature, and they reflect the aesthetic preferences and religious practices of the common people.

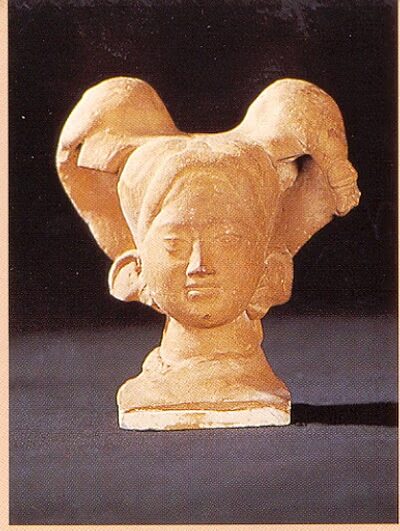

11.1 Terracotta Art

Terracotta art was a major component of Mauryan folk art. Terracotta, a material that is both affordable and easy to mold, was widely used to create figurines of humans, animals, and deities. These figurines were often used in domestic rituals, and they give us an important insight into the religious practices of the common people during the Mauryan period.

The female figurines in terracotta, often referred to as mother goddesses, are particularly notable. These figures were likely associated with fertility cults and were used in household worship. They were often adorned with elaborate jewelry and clothing, reflecting the aesthetic preferences of the time. The terracotta animal figurines also provide valuable information about the animals that were significant in Mauryan society, including horses, bulls, and elephants.

The terracotta pieces from this period are characterized by their stylized features and exaggerated expressions, which stand in contrast to the more naturalistic stone sculptures of court art. These figurines were often made using molds, which allowed for the mass production of similar figures, indicating that these objects were widely used by people across different regions of the Mauryan Empire.

11.2 Ring Stones and Disc Stones

Another important form of folk art in the Mauryan period is the production of ring stones and disc stones. These small, carved objects, found at various sites across northern India, are typically decorated with intricate designs, including geometrical patterns, floral motifs, and representations of animals such as lions, horses, and crocodiles.

The exact purpose of these objects remains unclear, but they are believed to have had some ritualistic or symbolic significance. The elaborate carvings on these stones suggest that they were valued for their artistic merit as well as their practical or religious uses. Ring stones were often circular with a hole in the center, and their small size indicates that they could have been worn or used as personal amulets.

The motifs on these stones—particularly the use of animals and plants—reveal a connection to the natural world and suggest that the people who used them had a close relationship with the land and its creatures. These objects are also evidence of a sophisticated artistic tradition that was thriving at the popular level, independent of the monumental art commissioned by the Mauryan rulers.

11.3 Yaksha and Yakshi Figures in Folk Art

While the Yaksha and Yakshi figures are commonly associated with Mauryan court art, their origins lie in the folk traditions of the time. These deities were worshipped in both rural and urban areas, and their association with fertility, nature, and wealth made them popular figures in Mauryan religious practice. The Yaksha figures are generally depicted as muscular male deities, often associated with the protection of wealth, while Yakshis are depicted as voluptuous female figures, embodying fertility and abundance.

The Yaksha and Yakshi statues are often found near water bodies, trees, and in village shrines, reflecting their connection to agricultural fertility and natural elements. These figures were often made in terracotta or stone, and they exhibit a wide range of styles, from highly polished and detailed sculptures to more rudimentary representations. Their presence across a wide geographic area suggests that their worship was widespread and deeply ingrained in the popular religious practices of the Mauryan period.

12. Influence of Mauryan Art on Later Periods

The artistic and architectural innovations of the Mauryan period had a profound influence on the development of Indian art in later periods, particularly during the Shunga, Kushan, and Gupta dynasties. The transition from wood to stone that began during the Mauryan period continued to shape Indian architecture for centuries, leading to the creation of even more elaborate stone temples, stupas, and sculptures.

The Ashokan pillars and their use of inscriptions as a medium for communicating state policy set a precedent for the use of stone as a tool of governance. This practice was adopted by subsequent rulers, who continued to use monumental inscriptions to assert their authority and record their achievements.

The Yaksha and Yakshi figures, which began as part of popular religious traditions, were absorbed into the Buddhist, Hindu, and Jain pantheons in later centuries, where they became important figures in the sculptural and temple art of these religions. The emphasis on naturalistic depictions of the human figure, first seen in Mauryan court sculpture, also laid the foundation for the development of the classical Indian style of sculpture that would reach its zenith during the Gupta period.

The stupa architecture initiated under Ashoka also had a lasting impact, with stupas becoming central elements of Buddhist religious architecture across Asia. The Great Stupa at Sanchi, for example, continued to be expanded and embellished by later dynasties, and it remains one of the most iconic examples of Buddhist architecture in India today.

Conclusion

The Mauryan Empire represents a pivotal moment in the history of Indian art, architecture, and sculpture. Under the patronage of rulers like Chandragupta Maurya and Ashoka, monumental stone architecture and sculptural traditions flourished, laying the groundwork for centuries of artistic innovation. The Ashokan pillars, with their intricate animal capitals and inscribed edicts, the widespread construction of stupas, and the development of rock-cut cave architecture all reflect the deep integration of political power, religious ideology, and artistic expression in the Mauryan period.

The artistic achievements of the Mauryan court were complemented by a rich tradition of folk art, which produced terracotta figurines, ring stones, disc stones, and Yaksha figures that captured the daily lives, beliefs, and aspirations of ordinary people. Together, these diverse forms of artistic expression reflect the vibrancy and complexity of Mauryan society, and their enduring legacy can be seen in the art and architecture of subsequent periods, from the Gupta Empire to the modern era.

The Mauryan period not only revitalized Indian art after centuries of decline but also created a cultural and artistic foundation that would influence the development of Indian civilization for centuries to come.

Read More :

Ancient History

- Harappan Civilization Date, Extent, and Characteristics

- Paleolithic Age in India

- Mesolithic Rock Paintings in India

- Neolithic Age in India

- Vedic Age in India

- The Significance of Megalithic Burials in India: Unearthing the Iron Age Heritage

- Expansion of Aryans in India: Migration, Settlement, and Cultural Evolution

- Formation of States (Mahajanapadas): Republics and Monarchies

- Jainism : An Overview of Ancient Indian Religions

- Buddhism – An Overview of Ancient Indian Religions

- Chandragupta Maurya

- Iranian and Macedonian Invasions of India and Their Impact

- Mauryan Art, Architecture, and Sculpture

- Megasthenes’ Indika

- Mauryan Empire: Foundation and Expansion

- Chanakya’s Arthashastra: A Book on Ancient Indian Statecraft

- Archaeological Sources: Excavation Epigraphy, Numismatics

- Prehistory and Proto-history : A detailed Analysis

[…] Mauryan Art, Architecture, and Sculpture : 4th Century BC Marvels (PDF Download […]

[…] Mauryan Art, Architecture, and Sculpture […]

[…] Mauryan Art, Architecture, and Sculpture : 4th Century BC Marvels (PDF Download […]

[…] Mauryan Art, Architecture, and Sculpture : 4th Century BC Marvels (PDF Download […]

Hi there to every one, the contents existing at this site are in fact awesome

for people experience, well, keep up the nice work

fellows.

my homepage – nordvpn coupons inspiresensation

Wonderful blog! I found it while surfing around on Yahoo News.

Do you have any suggestions on how to get listed

in Yahoo News? I’ve been trying for a while but I never seem to get there!

Thanks

My web site; nordvpn coupons inspiresensation –

t.co,