January 25, 2026 5:49 am

Introduction to History of Assam

The history of Assam and Ahom rule is a captivating saga of resilience, cultural synthesis, and eventual decline, spanning nearly six centuries of dominance in Northeast India. At the heart of this narrative lies the Moamoria Rebellion (1769–1805), a seismic upheaval that not only challenged the mighty Ahom kingdom but also set the stage for its ultimate downfall. Emerging in the lush Brahmaputra Valley, the Ahom dynasty, founded in 1228 by the Tai prince Sukaphaa, had weathered Mughal invasions, forged a unique multi-ethnic society, and established a sophisticated administrative system. Yet, by the late 18th century, cracks began to appear—social unrest, economic strain, and religious discord converged to spark one of the most significant revolts in Assam’s history. The Moamoria Rebellion wasn’t merely a fleeting uprising; it was a profound socio-religious and economic movement that eroded the foundations of Ahom supremacy, inviting foreign interventions that reshaped Assam’s destiny.

Why does this rebellion matter today? It marks a critical turning point in the “History of Assam and Ahom rule,” weakening a once-invincible kingdom and opening the door to Burmese invasions and British colonization. Far from a simple clash of arms, the rebellion reflected deep-seated grievances among marginalized communities, fueled by the egalitarian ideals of neo-Vaishnavism and the oppressive policies of Ahom rulers.

- APSC Notification 2025 OUT | APSC CCE 2025 Exam Date, Vacancy, Exam Pattern, Syllabus & Eligibility

- APSC Exam 2025: A Complete Guide for Aspirants

- APSC CCE Final Result 2023: Assam Public Service Commission Declares Results for Combined Competitive Examination

- APSC Result 2025: Date, Download PDF, and Merit List

- APSC Application Form 2025: Expected Release Date , How to Apply

- APSC Cut Off 2025: Expected Cut off, Everything You Need to Know

- APSC Exam 2025: Key Dates, Eligibility, Admit Card, Syllabus, and Exam Pattern

- APSC Syllabus 2025: Subject-Wise Topics for APSC Prelims, Mains, and Interview

Historical Context of the Ahom Kingdom

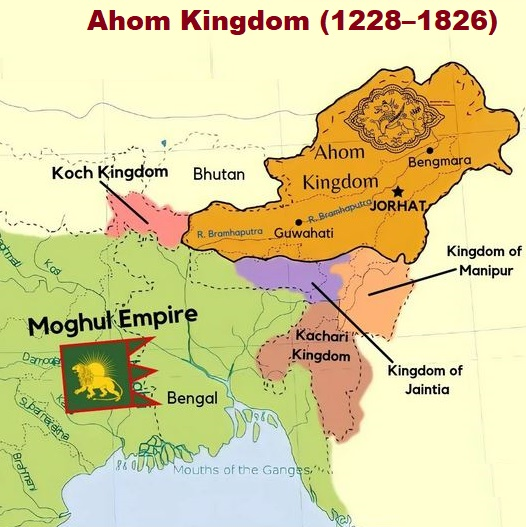

To grasp the significance of the Moamoria Rebellion, we must first journey into the remarkable “History of Assam and Ahom rule,” a tale of conquest, adaptation, and cultural fusion that defined Northeast India for nearly six centuries. The Ahom kingdom’s origins trace back to 1228, when Sukaphaa, a Tai prince from Mong Mao (in present-day Yunnan, China), crossed the Patkai hills into the Brahmaputra Valley. Unlike typical conquerors, Sukaphaa didn’t impose his will through brute force; he sought alliances with local tribes like the Morans and Barahis, laying the groundwork for a kingdom that blended Tai traditions with indigenous Assamese culture. Over time, this small principality grew into a formidable power, its rulers—known as Swargadeos (heavenly kings)—expanding their domain across Assam’s fertile plains and rugged hills.

The Ahom kingdom reached its zenith in the 16th and 17th centuries, a golden age that solidified its place in the “History of Assam and Ahom rule.” Under Swargadeo Suhungmung (1497–1539), the kingdom embraced a multi-ethnic identity, incorporating communities like the Chutias and Kacharis through diplomacy and military campaigns. This era also saw the development of the Paik system, a unique labor-based structure where every able-bodied man, or paik, served the state as a soldier, farmer, or laborer in exchange for land. This system fueled the kingdom’s military might and economic stability, enabling it to repel Mughal invasions, most famously at the Battle of Saraighat in 1671 under Lachit Borphukan. This iconic victory against Mir Jumla’s forces showcased Ahom resilience and naval prowess, a triumph still celebrated in Assam’s collective memory.

Yet, the Ahom kingdom wasn’t just a military powerhouse; it was a crucible of cultural and religious transformation. In the 16th century, the neo-Vaishnavite movement, spearheaded by the saint-reformer Srimanta Sankardeva, swept through Assam, challenging orthodox Hinduism and the Ahom rulers’ patronage of Shaktism. Sankardeva’s egalitarian teachings, spread through sattras (monastic centers), emphasized devotion over ritualistic hierarchy, attracting lower castes and marginalized groups disillusioned by the Paik system’s demands. These sattras became sanctuaries of learning and spirituality, subtly undermining the state’s control over its subjects. By offering refuge from forced labor, they planted seeds of dissent that would later sprout into rebellion.

By the 18th century, however, the Ahom kingdom’s golden era had faded. Economic stagnation crept in as trade routes shifted and agricultural yields faltered under the strain of an overextended Paik system. Internal strife intensified as royal succession disputes and noble factionalism weakened centralized authority. Meanwhile, the growing influence of sattras, particularly the Mayamara Sattra among the Moran tribe, clashed with the monarchy’s religious policies, setting a volatile stage. Kings like Siba Singha (1714–1744) and his consort Phuleswari escalated tensions by imposing Shakta rituals on Vaishnava followers, alienating large swathes of the population. This simmering discontent, rooted in social, economic, and religious fissures, made the kingdom ripe for upheaval. The Moamoria Rebellion would soon erupt, forever altering the “History of Assam and Ahom rule”—a story of a kingdom undone not by external foes, but by its own internal contradictions.

Causes of the Moamoria Rebellion

The Moamoria Rebellion ranks among the most pivotal chapters in the “History of Assam and Ahom rule,” a cataclysmic event born not from a fleeting dispute but from a tangled web of grievances that had long plagued the Ahom kingdom. By the late 18th century, this once-mighty dynasty faced a reckoning, as socio-religious tensions, economic hardship, and political tyranny converged to ignite a revolt that would echo through Assam’s history. To unravel why this uprising shattered a 600-year-old regime, we must explore its intricate causes—each a fracture in the edifice of Ahom rule.

Socio-Religious Tensions: A Clash of Beliefs

Central to the rebellion was a profound religious conflict, pitting the neo-Vaishnavite ideals of the Moamorias against the Shaktism favored by Ahom rulers. The Moamorias, devotees of the Mayamara Sattra—established by Aniruddhadeva, a follower of Srimanta Sankardeva—championed a faith that rejected caste distinctions and elaborate ceremonies. This egalitarian creed resonated with marginalized groups like the Morans, Mataks, and Kacharis, who found solace in its simplicity. In contrast, the Ahom monarchy upheld Shakta rituals, involving animal sacrifices and priestly authority, which clashed with Vaishnava principles. Tensions boiled over during the reign of Siba Singha (1714–1744), when his consort, Phuleswari, sought to impose Shakta dominance. Her decree to smear sattradhikars (Vaishnava monastic leaders) with animal blood was an outrage that galvanized the Moamoria community, transforming their sattras into centers of defiance. This religious persecution fueled a broader movement that destabilized the kingdom.

Economic Distress: The Crumbling Paik System

The rebellion’s roots also lay in economic discontent, driven by the faltering Paik system—the backbone of Ahom governance. This labor framework compelled every able-bodied man, known as a paik, to serve the state as a soldier, farmer, or worker in return for land rights. While it once sustained the kingdom’s prosperity, by the 18th century, it had become a burden. Economic decline, marked by shrinking trade and failing harvests, strained the system, while its unrelenting demands alienated the peasantry. Tribes like the Morans bore the brunt, their labor exploited without relief. The rise of sattras offered an alternative: by joining these communities, paiks could escape state duties, sapping the Ahom administration of its workforce. As royal coffers emptied and officials grew ruthless, economic frustration morphed into a revolutionary force. Explore the Paik system’s role in-depth at . https://learnpro.in/paik-system-in-assam/

Political Tyranny: The Weight of Oppression

The Ahom elite’s arrogance provided the final push toward rebellion. Decades of political misrule had eroded trust in the monarchy. Kings like Gadadhar Singha (1681–1696) persecuted Vaishnavas, while Rudra Singha (1696–1714) deepened divisions by favoring certain nobles. By the reign of Lakshmi Singha (1769–1780), the nobility’s excesses had reached a breaking point. Enter Kirtichandra Barbarua, a domineering Ahom official whose actions epitomized this oppression. In 1769, he ordered the public flogging of Nahar Khora, a Moran chief, and Ragha Moran for failing to meet Paik obligations—an act that insulted their dignity and inflamed their followers. This wasn’t an isolated cruelty but part of a pattern of disdain for tribal autonomy and rural plight, driving the Moamorias to revolt.

The Trigger: A Humiliation Too Far

The rebellion ignited in 1769 with a single, explosive incident: Kirtichandra’s flogging of Nahar Khora and Ragha Moran. For the Morans, this wasn’t just punishment—it was a stark symbol of their subjugation under an increasingly despotic regime. United under the Mayamara Sattra’s banner, they struck back, storming the Ahom capital, Rangpur, and launching a rebellion that would redefine the “History of Assam and Ahom rule.” This wasn’t merely a reaction to one event; it was the climax of years of religious suppression, economic exploitation, and political arrogance—a storm the Ahom kingdom was powerless to quell.

Key Figures of the Moamoria Rebellion

The Moamoria Rebellion, a defining moment in the “History of Assam and Ahom rule,” was not just a faceless uprising but a movement driven by remarkable individuals whose actions altered the course of Ahom history. From rebel leaders who defied the monarchy to Ahom kings who struggled to retain power, these figures embodied the rebellion’s complexity—its triumphs, its chaos, and its enduring legacy.

Ragha Moran: The Reluctant Revolutionary

At the forefront of the rebellion stood Ragha Moran, a Moran tribal leader whose defiance sparked the initial uprising. In 1769, after enduring public flogging by Kirtichandra Barbarua for failing to meet Paik system demands, Ragha rallied the Moamorias under the Mayamara Sattra’s banner. His leadership saw the rebels storm Rangpur, the Ahom capital, where they briefly installed him as a puppet ruler. Yet, Ragha lacked the political acumen to govern, and his reign was short-lived as royalists recaptured the city. His role, though fleeting, symbolized the Moran tribe’s pent-up fury and set the rebellion in motion.

Nahar Khora: The Catalyst of Defiance

Closely tied to Ragha was Nahar Khora, another Moran chief whose humiliation in 1769 alongside Ragha lit the rebellion’s fuse. As a respected figure among the Moamorias, his flogging by Kirtichandra galvanized the community. After the initial uprising, his son, Ramakanta, briefly ruled as a rebel king during the chaos of Rangpur’s capture. Nahar’s legacy lies in his role as a trigger—his suffering transformed personal grievance into collective resistance against Ahom oppression.

Sarbananda Singha: Architect of the Matak Rajya

Emerging later in the rebellion, Sarbananda Singha proved a more enduring leader. A Moamoria commander, he rose to prominence in the 1790s, negotiating with Purnananda Burhagohain to establish the semi-independent Matak Rajya in Bengmara (modern Tinsukia). This enclave, carved out of Ahom territory, showcased his strategic vision, offering the Matak tribe autonomy amid the kingdom’s decline. Sarbananda’s reign marked a lasting fracture in Ahom rule, a testament to the rebellion’s impact.

Lakshmi Singha: The Embattled King

On the Ahom side, Lakshmi Singha (1769–1780) reigned during the rebellion’s explosive onset. Captured and imprisoned by Moamoria rebels in 1769, his plight symbolized the monarchy’s vulnerability. Though later restored by loyalists, his rule was marred by instability, reflecting the Ahom kingdom’s inability to quell dissent. Lakshmi’s captivity underscored how the rebellion shook the very throne of Ahom power.

Gaurinath Singha: The King Who Sought Foreign Aid

Succeeding Lakshmi, Gaurinath Singha (1780–1794) faced the rebellion’s resurgence. When Moamorias recaptured Rangpur in 1788, he fled, seeking help from the British East India Company. In 1792, Captain Welsh led a force to restore Ahom control, a move that suppressed the rebels but exposed Assam to foreign influence—a precursor to British colonization.

Kirtichandra Barbarua: The Villain of Oppression

Finally, Kirtichandra Barbarua, a ruthless Ahom noble, unwittingly fueled the revolt. His flogging of Ragha and Nahar in 1769, coupled with his disdain for tribal communities, made him a hated figure. Captured and executed by rebels, his death marked a symbolic victory for the Moamorias, amplifying their resolve.

These figures—rebels and rulers alike—wove the “History of Assam and Ahom rule” into a narrative of resistance and retribution, their legacies enduring beyond the rebellion’s end.

Phases and Events of the Moamoria Rebellion

The Moamoria Rebellion unfolded over nearly four decades (1769–1805), a tumultuous chapter in the “History of Assam and Ahom rule” that saw the Ahom kingdom teeter on the brink of collapse. Far from a single, unified campaign, it progressed through distinct phases—each marked by fierce battles, shifting fortunes, and a gradual erosion of Ahom authority. From the initial capture of Rangpur to the rise of the Matak Rajya, these events reveal a rebellion that was as chaotic as it was consequential, reshaping Assam’s political landscape.

First Phase (1769–1770): The Fall of Rangpur

The rebellion erupted in 1769, triggered by Kirtichandra Barbarua’s flogging of Ragha Moran and Nahar Khora. Enraged, the Moamorias, backed by the Mayamara Sattra, launched a daring assault on Rangpur, the Ahom capital. Their swift victory stunned the kingdom: they captured Lakshmi Singha, imprisoned him, and briefly installed Ragha as a figurehead ruler. This audacious move exposed the Ahom monarchy’s fragility, as tribal warriors overran a city once thought impregnable. However, the triumph was short-lived. By 1770, Ahom loyalists, led by nobles like Purnananda Burhagohain, rallied to reclaim Rangpur. Their counterattack was brutal—massacres depopulated Moran areas, and the rebels retreated, their early gains undone by a lack of cohesive strategy.

Guerrilla Warfare (1770–1788): A War of Attrition

The rebellion didn’t end with Rangpur’s recapture; it morphed into a prolonged struggle. Scattered Moamoria forces, under leaders like Lephora and Parmananda, withdrew to the jungles and hills of eastern Assam, waging guerrilla warfare against Ahom troops. This phase saw no grand battles but a relentless campaign of ambushes and raids, targeting royal outposts and supply lines. The Ahom administration, already strained by economic woes and the faltering Paik system, struggled to suppress these hit-and-run tactics. Meanwhile, Lakshmi Singha’s restored reign remained shaky, his authority undermined by ongoing unrest. For nearly two decades, this low-intensity conflict bled the kingdom dry, setting the stage for a renewed rebel offensive.

Second Phase (1788–1794): The Return to Rangpur

By 1788, the Moamorias regrouped, their resolve hardened by years of resistance. They launched a second assault on Rangpur, once again seizing the capital and forcing Gaurinath Singha, Lakshmi’s successor, to flee to Guwahati. This resurgence showcased the rebels’ persistence, as they exploited the Ahom kingdom’s internal divisions and dwindling resources. Gaurinath, desperate to regain control, turned to the British East India Company for aid. In 1792, Captain Welsh arrived with a small force, marking the first British intervention in Assam. By 1794, his troops, alongside Ahom loyalists, recaptured Rangpur, crushing the rebel stronghold. This victory came at a cost: foreign involvement signaled the kingdom’s dependence on external powers, a vulnerability that would later prove fatal.

Final Phase (1794–1805): The Rise of the Matak Rajya

The British-backed suppression didn’t end the rebellion’s impact. In its final phase, Sarbananda Singha, a shrewd Moamoria leader, emerged as a key figure. After negotiations with Purnananda Burhagohain, he secured control of Bengmara (modern Tinsukia), establishing the Matak Rajya—a semi-independent state within Ahom territory. This arrangement, formalized around 1805, reflected a pragmatic compromise: the Ahom monarchy, too weakened to govern its eastern reaches, ceded autonomy to the Mataks. Sarbananda’s rule endured, creating a buffer zone that outlasted the rebellion itself. This fragmentation highlighted the Ahom kingdom’s irreversible decline, as regional powers carved out their own domains. Learn more about this regional shift at .

Together, these phases—from the bold sieges of Rangpur to the guerrilla struggles and the Matak Rajya’s rise—illustrate the “History of Assam and Ahom rule” at a crossroads. The Moamoria Rebellion wasn’t just a war; it was a slow unraveling of a dynasty, exposing its weaknesses to internal dissent and external opportunists. Its events, chaotic and sprawling, paved the way for the Burmese invasions and British colonization that soon followed, forever altering Assam’s trajectory.

Consequences of the Moamoria Rebellion

The Moamoria Rebellion left an indelible mark on the “History of Assam and Ahom rule,” its reverberations dismantling a dynasty that had ruled for nearly six centuries. Far from a fleeting disruption, this uprising—spanning 1769 to 1805—triggered a cascade of consequences that weakened the Ahom kingdom, fractured its unity, and opened Assam to foreign domination. Its aftermath reshaped the region’s political, social, and cultural landscape, signaling the end of an era and the dawn of a new, colonial chapter.

Weakening of the Ahom Kingdom

The rebellion inflicted catastrophic damage on the Ahom monarchy. Estimates suggest that nearly half of Assam’s population perished due to warfare, massacres, and famine, decimating the labor pool that sustained the Paik system. This economic backbone, already strained before the revolt, collapsed entirely, leaving the kingdom unable to fund its armies or maintain infrastructure. Internal divisions deepened as nobles vied for power, and Ahom kings like Gaurinath Singha struggled to assert control. The once-formidable dynasty, which had repelled Mughal invasions, now stood hollowed out, its authority eroded by decades of relentless conflict.

Rise of the Matak Rajya

A tangible outcome of the rebellion was the emergence of the Matak Rajya, a semi-independent state under Sarbananda Singha. Carved out of eastern Assam around 1805, this enclave in Bengmara (modern Tinsukia) symbolized the Ahom kingdom’s territorial losses. The Mataks, bolstered by their Moamoria roots, governed autonomously, paying only nominal tribute to the Ahom crown. This fragmentation underscored the monarchy’s inability to unify its realm, as regional powers asserted their own sovereignty—a legacy of the rebellion’s divisive force. .

Burmese Invasions: A Kingdom Overrun

The rebellion’s toll left Assam vulnerable to external threats, most notably the Burmese invasions of 1817–1826. With the Ahom kingdom depleted, Burmese forces from Ava (modern Myanmar) swept in, exploiting its weakened defenses. Three successive invasions ravaged the region, slaughtering thousands and plunging Assam into chaos. The Ahom monarchy, led by figures like Chandrakanta Singha, could muster little resistance, their armies shattered and their coffers empty. This foreign incursion, a direct consequence of the rebellion’s devastation, marked the final blow to Ahom sovereignty.

British Colonization: The End of an Era

The Burmese occupation paved the way for British colonization, sealing the fate of the “History of Assam and Ahom rule.” In 1826, the Treaty of Yandabo, signed after the First Anglo-Burmese War, transferred Assam to the British East India Company. The Ahom kingdom, already a shadow of its former self, was formally dissolved, its rulers reduced to pensioned figureheads. The British imposed their administration, introducing tea plantations and colonial governance that transformed Assam’s economy and society. This shift, catalyzed by the rebellion’s weakening of indigenous rule, marked the region’s entry into a new historical epoch.

Socio-Cultural Legacy

Beyond politics, the rebellion empowered Assam’s neo-Vaishnavite communities, particularly the Moamorias. Their resistance elevated the influence of sattras, fostering a cultural legacy of egalitarianism that endured under British rule. Marginalized groups, once oppressed by the Paik system, gained a voice, reshaping Assam’s social fabric with ideals rooted in Sankardeva’s teachings.

In the end, the Moamoria Rebellion was a harbinger of collapse, unraveling the “History of Assam and Ahom rule” and ushering in foreign dominion. Its consequences—devastation, division, and transformation—linger as a testament to a kingdom undone by its own internal strife.

Conclusion

The Moamoria Rebellion stands as a monumental turning point in the “History of Assam and Ahom rule,” a saga of defiance that unraveled a dynasty once deemed unassailable. Spanning 1769 to 1805, this uprising was far more than a clash of arms—it was a socio-religious upheaval, an economic revolt, and a political reckoning that exposed the vulnerabilities of the Ahom kingdom. From the fiery capture of Rangpur to the rise of the Matak Rajya, the rebellion’s phases revealed a kingdom fractured by its own contradictions: a rigid Paik system, a clash between neo-Vaishnavism and Shaktism, and the arrogance of nobles like Kirtichandra Barbarua. Figures such as Ragha Moran, Sarbananda Singha, and Gaurinath Singha shaped this turbulent narrative, their actions echoing through Assam’s past.

The consequences were profound. The rebellion gutted the Ahom monarchy, slashing its population and resources, and left it defenseless against the Burmese invasions that followed. By 1826, the Treaty of Yandabo handed Assam to the British, ending six centuries of Ahom rule and ushering in colonial dominance. Yet, amidst the ruin, the rebellion sowed seeds of cultural resilience, empowering sattras and marginalized communities with a legacy that outlived the kingdom itself. This wasn’t just the fall of a dynasty; it was a bridge between medieval Assam and its modern identity, forged in the crucible of resistance.

For history enthusiasts and curious minds alike, the Moamoria Rebellion offers a window into Assam’s rich, complex past—a story of power, struggle, and transformation. Want to explore more? Delve into the broader tapestry of Assam’s heritage at , where the echoes of the Ahom era await. Share your thoughts below—what lessons does this rebellion hold for us today?