January 25, 2026 12:31 pm

1. Introduction

The ancient invasions of India by foreign powers, particularly the Iranian and Macedonian invasions, had profound effects on the subcontinent. These invasions not only altered the political landscape but also introduced cultural, economic, and administrative changes that shaped Indian civilization in significant ways. The Iranian invasion under the Achaemenid Empire and the later Macedonian invasion led by Alexander the Great were critical in connecting India to the larger Persian and Hellenistic worlds, leading to exchanges in trade, art, administration, and military tactics.

Both invasions, despite their limited direct control, left a lasting legacy that influenced subsequent Indian empires like the Mauryas. This detailed study examines these invasions, analyzing their causes, consequences, and the historical accounts left by early Greek and Roman historians about India during these turbulent times.

2. Iranian Invasion of India (550 – 515 B.C.)

2.1 Background of the Achaemenid Empire

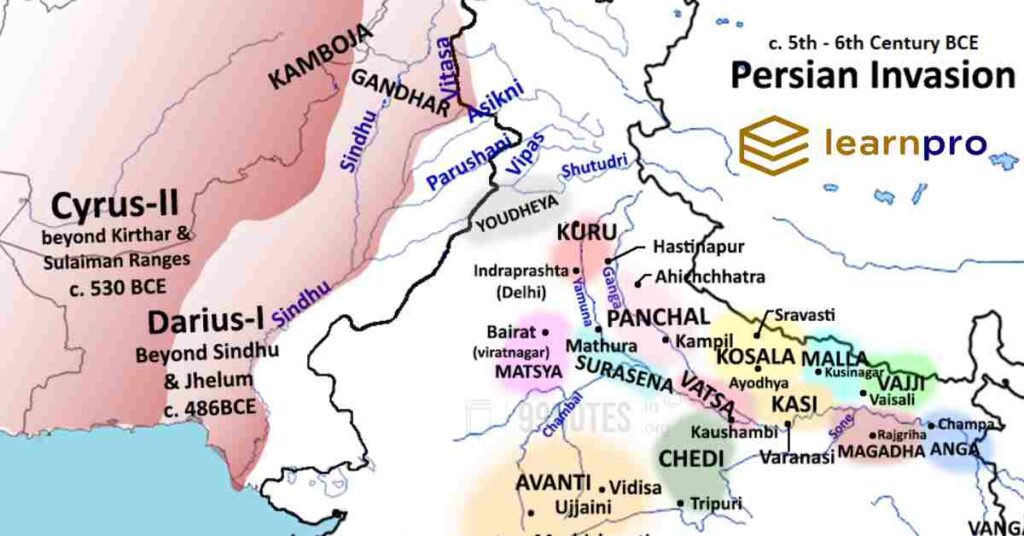

The Achaemenid Empire, established by Cyrus the Great in 550 B.C., rapidly expanded to become one of the largest empires in ancient history, stretching from Anatolia and Egypt to the Indus Valley. The expansion into the east of Iran, including parts of modern Afghanistan and the northwest of the Indian subcontinent, marked the beginning of Persian influence on Indian history. Cyrus began a series of military campaigns in the east, which laid the foundation for Persian control over parts of the Indian subcontinent, particularly in the Gandhara region (modern-day Pakistan).

Cyrus’s expansion into the Indian borderlands, while not as extensive as his campaigns in the west, set the stage for future Persian rulers, notably Darius I, to further extend Persian control into India.

2.2 Cyrus the Great’s Campaigns in the East

Cyrus’s campaigns toward the east, particularly in Gandhara, a region situated at the crossroads between Central Asia and the Indian subcontinent, established a foothold for future Persian conquests. His campaigns were primarily focused on securing the Persian Empire’s eastern frontiers, which included modern-day Afghanistan and parts of the northwestern Indian subcontinent. This region was strategically significant due to its location along major trade routes connecting Persia with the Indian subcontinent.

Though Cyrus did not conduct a full-scale invasion of India, his military activities in the region laid the groundwork for future Persian incursions. His conquests allowed Persia to control key trade routes, and his successors, notably Darius I, would build upon this by extending Persian influence deeper into the Indian subcontinent.

2.3 Darius I and the Expansion into India

Darius I (522-486 B.C.), the third king of the Achaemenid Empire, is credited with the first significant Persian expansion into India. In 516 B.C., Darius led an expedition that resulted in the annexation of territories in Punjab, Sindh, and the North-Western Frontier Province. This marked the beginning of Persian dominance in the region, which would last until the Macedonian invasion led by Alexander the Great.

Darius’s expansion into India was driven by both strategic and economic considerations. The rich resources of the Indus Valley, particularly gold, timber, and other valuable goods, made the region a lucrative addition to the Persian Empire. Additionally, controlling the northwestern territories of India allowed Persia to secure its eastern borders and maintain dominance over the trade routes between India and Central Asia.

The Behistun Inscription, one of the most famous inscriptions from the reign of Darius I, refers to Gandhara as a province of the Persian Empire, inherited from Cyrus the Great. This inscription, written in multiple languages, serves as a testament to the Persian Empire’s vastness and its ability to integrate diverse cultures and regions under its control.

2.4 Persian Administration in India: The Satrapy System

One of the most enduring impacts of the Persian invasion was the introduction of the satrapy system of administration. Under this system, the Persian Empire was divided into provinces, known as satrapies, each governed by a satrap or provincial governor. These governors were responsible for collecting taxes, maintaining order, and ensuring the loyalty of the province to the Persian king. In India, the regions conquered by Darius were incorporated into the empire’s twentieth satrapy.

Herodotus, the ancient Greek historian, provides valuable insights into the administration of the Indian satrapy under the Persians. He mentions that the Indian satrapy was one of the most prosperous in the empire, paying an annual tribute of 360 talents of gold dust. This wealth likely came from the gold-rich mines of Dardistan and the upper Indus River, as well as from the fertile lands of Punjab and Sindh.

The satrapy system not only facilitated Persian control over the distant territories of India but also introduced a centralized form of governance that influenced later Indian rulers. The Mauryan Empire, established after the decline of the Persian and Macedonian influence, adopted several aspects of Persian administration, particularly the satrap system, which helped maintain control over vast territories.

2.5 Persian Naval Expeditions to India

In addition to his land-based campaigns, Darius I was keen on exploring and utilizing the maritime routes of the Indian subcontinent. In 517 B.C., Darius dispatched a naval expedition under the leadership of Scylax of Caryanda, a Greek explorer, to survey the Indus River and its basin. This expedition was significant in that it expanded the Persian Empire’s geographical knowledge of the Indian subcontinent and opened up new maritime trade routes.

The exploration of the Indus River also helped solidify Persian control over the region, allowing Darius to better integrate the Indian territories into the empire’s vast trade network. The maritime routes opened by Scylax facilitated trade between India and Persia, as well as other parts of the Achaemenid Empire,, such as Babylonia and Egypt. This increased connectivity led to a flourishing exchange of goods, culture, and ideas between India and Persia.

2.6 Extent of the Persian Empire in India

Under Darius I, Persian control in India extended beyond Gandhara and the North-Western Frontier to include significant portions of Punjab and the Lower Indus Valley. The Persian Empire’s influence in India reached its zenith during this period, with the region becoming fully integrated into the administrative and economic structure of the Achaemenid Empire.

The Persian Empire’s control over these regions was primarily focused on securing valuable resources and maintaining strategic dominance over the trade routes that connected India with Central Asia and the Middle East. Teak and gold were among the most significant resources extracted from India during this period, with Persian inscriptions indicating that teak from Gandhara was used in the construction of Darius’s palace at Susa.

Although Persian control in India was limited to the northwestern regions, it had a lasting impact on the political and cultural landscape of the subcontinent. Persian influence persisted in these regions long after the decline of the Achaemenid Empire,, particularly through the adoption of administrative practices, art, and architecture.

2.7 Persian Domination Under Xerxes and His Successors

Xerxes I (486-465 B.C.), the successor of Darius I, maintained Persian control over the Indian provinces but did not pursue further expansion into the subcontinent. His reign was marked by the famous conflict with Greece, during which Indian soldiers were requisitioned to fight in the Greco-Persian Wars. Herodotus notes that Xerxes brought a contingent of Indian troops, including infantry and cavalry, to fight in the Persian invasion of Greece.

The defeat of Xerxes in Greece marked the beginning of the decline of Persian power, but Persian rule over northwestern India continued. Darius III, the last of the Achaemenid rulers, summoned Indian troops to fight against Alexander the Great during his conquest of Persia in 330 B.C.. However, with the fall of Darius III and the collapse of the Achaemenid Empire, Persian control over India came to an end.

3. Impact of the Iranian Invasions on India

3.1 Political Impact of the Iranian Invasions

The Iranian invasions and subsequent domination of parts of northwestern India had far-reaching consequences for the region. Politically, the Persian control of these territories exposed the weaknesses of Indian defense systems in the northwest, paving the way for further invasions by foreign powers, including the Greeks, Sakas, Kushanas, and Huns. However, Persian rule did not have a direct, lasting political influence on India, as the core of the Indian subcontinent remained largely unaffected by Persian governance.

One significant political lesson learned from the Iranian invasions was the necessity for a strong, unified empire to repel foreign invasions. The fragmented and disunited nature of the Indian states, particularly in the northwest, made them vulnerable to external aggression. This realization later contributed to the unification of the subcontinent under the Mauryan Empire.

Additionally, the satrap system introduced by the Persians in their Indian provinces served as a model for later dynasties, particularly the Sakas and Kushanas, who ruled in the northwest. This administrative framework helped maintain control over large territories and facilitated the collection of taxes and resources.

3.2 Economic Impact: Encouragement of Trade

One of the most significant impacts of the Persian invasion was the expansion of trade between India and Persia. The establishment of Persian control over northwestern India opened up new trade routes, both overland and by sea, connecting the Indian subcontinent with the wider Persian Empire and beyond. These trade routes facilitated the exchange of goods such as ivory, teak, spices, and textiles from India, while Persian goods, including silver and luxury items, flowed into the Indian market.

The exploration of the Indus River and the opening of new maritime routes in the Arabian Sea under Darius I played a crucial role in fostering trade. Indian merchants gained access to markets in Persia, Asia Minor, and other parts of the Persian Empire, boosting the economy of northwestern India. In particular, Indian traders reached as far as the Persian Gulf and Egypt, creating long-lasting commercial ties.

3.3 Settlement of Foreigners on Indian Soil

The Iranian invasion led to the settlement of foreigners in the northwestern regions of India. Over time, Persians, Greeks, Turks, and other groups settled in the region, particularly in areas like Gandhara and Punjab. These foreigners were absorbed into the local population and contributed to the development of a cosmopolitan society. The mixing of different cultures, languages, and traditions in these areas created a unique cultural and social environment that would continue to evolve over the centuries.

This process of cultural assimilation was further accelerated by the arrival of Greek settlers after Alexander’s invasion, as well as later invasions by the Sakas and Kushanas. These waves of foreign influence left a lasting mark on the region’s art, architecture, and social customs.

3.4 Cultural Impact: Influence on Art and Architecture

The Achaemenid Persian influence on Indian art and architecture is evident in several aspects of Indian cultural heritage, particularly in the Mauryan period. Persian craftsmanship, characterized by high-quality masonry and intricate designs, influenced Indian artisans and builders. This can be seen in the famous Ashokan pillars, which bear a striking resemblance to Persian pillars in their polished finish and monumental scale.

Megasthenes, the Greek ambassador at the court of Chandragupta Maurya, noted that the Mauryan ruler adopted certain Persian ceremonies and rituals, indicating the cultural exchange between the two regions. The Mauryan sculptures and the polished stone pillars erected by Ashoka were likely inspired by Persian models, particularly in their use of smooth, polished stone and their monumental scale.

The most significant example of Persian influence on Indian architecture is the Kharoshthi script, which developed from the Aramaic script introduced by the Persians. The Kharoshthi script was used primarily in the northwestern regions of India and was inscribed on Ashokan rock edicts in this area. This script, written from right to left, demonstrates the deep cultural and administrative ties between Persia and India during this period.

3.5 Influence on Coinage

The Persian invasion also left a lasting impact on the coinage system in India. The introduction of Persian silver coins into the northwestern regions influenced the minting techniques used by local rulers. Persian coins were known for their high quality, refined minting, and elegant designs, and these attributes were soon adopted by Indian rulers. Prior to Persian influence, Indian coinage was rudimentary, and most of the economy operated on a barter system or through the use of precious metals as raw currency.

Under the influence of the Achaemenid Persian Empire, Indian rulers began to adopt more sophisticated techniques for minting coins. The Mauryan Empire, for instance, introduced silver coins that were inspired by Persian minting techniques. These coins played a critical role in the development of a monetary economy in India, facilitating trade and commerce within the subcontinent and with neighboring regions such as Persia and Greece. The Persian influence on Indian coinage would continue to shape the evolution of currency in India for centuries.

3.6 Development of the Kharoshthi Script

Another significant cultural impact of the Iranian invasion was the introduction and development of the Kharoshthi script in India. The Kharoshthi script was based on the Aramaic script, which was brought to the Indian subcontinent by the Persian administrators during the Achaemenid rule. The Aramaic script was used in the Persian Empire as a form of administrative and legal writing, and it quickly took root in the regions of Gandhara and Punjab after their annexation by Darius I.

The Kharoshthi script, which was written from right to left, became widely used in the northwestern parts of India, particularly for inscriptions and official decrees. Most notably, Ashoka’s edicts in these regions were inscribed using the Kharoshthi script, demonstrating the extent to which Persian influence had permeated the administrative practices of the region.

Over time, the Kharoshthi script became one of the principal writing systems in India, particularly in the northwest, and was used for a variety of purposes, including commerce, literature, and governance. This script would eventually be supplanted by other writing systems, but its development during the period of Persian rule left a lasting legacy on Indian culture and administration.

3.7 Interchange of Indo-Persian Culture

The interactions between the Persian Empire and India facilitated a rich interchange of culture and ideas. Indian scholars and intellectuals traveled to Persia, where they engaged with their Persian counterparts in discussions about philosophy, governance, and religious practices. Similarly, Persian scholars visited India, bringing with them new ideas about administration, law, and culture.

This interchange of ideas led to a fusion of Indo-Persian culture, particularly in the areas of art, religion, and philosophy. The influence of Persian administrative practices on the Indian subcontinent can be seen in the Mauryan period, where Persian concepts of governance, such as the satrapy system, were adapted to suit local needs. Persian influence on Indian religious thought is also evident, as elements of Zoroastrianism blended with Indian philosophical traditions, contributing to the development of new forms of religious practice.

The fusion of Indo-Persian art is most clearly seen in the Gandhara School of Art, which flourished in the northwestern regions of India. This artistic style combined Persian, Greek, and Indian influences, creating a unique form of sculpture and architecture that was particularly associated with Buddhist art. The Gandhara style would later become one of the defining features of Indian art, particularly in the representations of the Buddha and other religious figures.

3.8 Influence on Mauryan Administration

The political and administrative influence of the Persian Empire on India was most clearly seen in the development of the Mauryan Empire. Chandragupta Maurya, the founder of the Mauryan dynasty, is said to have been inspired by the Achaemenid model of governance, particularly the use of provincial governors (satraps) to manage distant regions of the empire. The Mauryan administration adopted many elements of the Persian system, including a centralized bureaucracy, a system of taxation, and a network of roads that facilitated communication and commerce across the empire.

Megasthenes, the Greek ambassador to the court of Chandragupta Maurya, noted the similarities between the Mauryan and Persian systems of governance. The Mauryan state, like the Persian Empire, relied on a network of provincial administrators, who were responsible for maintaining order, collecting taxes, and ensuring loyalty to the central government. This system allowed the Mauryan Empire to govern vast territories efficiently, and it would serve as a model for later Indian empires as well.

3.9 Influence on Indian Diplomacy

The Persian invasions also introduced new forms of diplomatic practices in India. The Achaemenid Empire was known for its diplomatic relations with neighboring powers, and this model of diplomacy was adopted by Indian rulers during the Mauryan period. The use of ambassadors, treaties, and diplomatic marriages became an important tool for Indian rulers to maintain relations with neighboring kingdoms and empires.

One notable example of Persian influence on Indian diplomacy was the presence of foreign ambassadors at the court of Chandragupta Maurya. Megasthenes, a Greek ambassador from the Seleucid Empire, resided at the Mauryan court, where he provided detailed accounts of Indian society, governance, and military organization. Similarly, Indian rulers sent envoys to foreign courts, including those of Persia and Greece, to establish trade agreements and diplomatic relations.

The use of diplomacy as a tool for maintaining peace and trade was a hallmark of Persian influence on Indian politics. This tradition of diplomatic engagement would continue throughout Indian history, particularly during the reigns of subsequent dynasties such as the Guptas and Mughals.

4. Macedonian Invasion of India (326 B.C.)

4.1 Background of Alexander the Great’s Invasion

Alexander the Great was born in 356 B.C. in the kingdom of Macedon, located in northern Greece. Following the assassination of his father, Philip II, Alexander ascended the throne at the young age of twenty. Over the next decade, Alexander embarked on one of the most extraordinary military campaigns in history, conquering Egypt, Syria, Persia, and much of the known world. By 330 B.C., Alexander had defeated Darius III, the last of the Achaemenid rulers, and had established his dominance over the Persian Empire.

With the defeat of Persia, Alexander turned his attention to India, which he had heard about from Persian sources. Greek historians, including Herodotus, had written about the wealth and vastness of India, and Greek philosophers were intrigued by Indian culture, religion, and philosophy. This curiosity, combined with Alexander’s desire to expand his empire further east, motivated him to launch an invasion of India.

4.2 Alexander’s Campaign in India

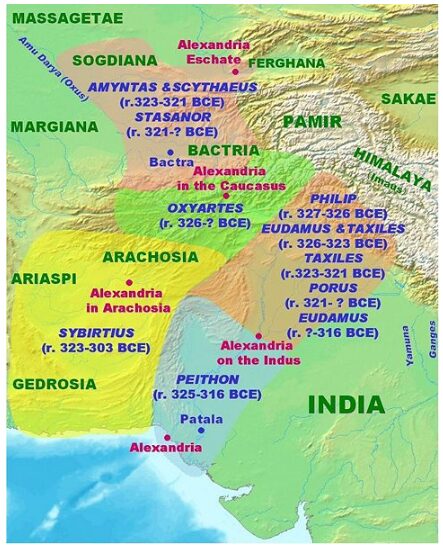

In 326 B.C., Alexander crossed the Hindu Kush mountains into the Indian subcontinent, marking the beginning of his Indian campaign. He was accompanied by a large and well-trained army, including Macedonian infantry, cavalry, and siege weapons. Alexander’s invasion was initially met with little resistance, as many local rulers in the northwest chose to surrender or enter into alliances with him. One such ruler was Ambhi, the king of Taxila, who welcomed Alexander and offered his support in exchange for protection against his rival, Porus.

Alexander’s army advanced through Taxila and prepared to face the forces of Porus, who ruled the region between the Jhelum and Chenab rivers. The ensuing Battle of Hydaspes (326 B.C.) was one of the most famous battles of Alexander’s career. Despite being vastly outnumbered, Alexander employed clever tactics to cross the flooded Jhelum River and surprise Porus’s forces. After a fierce and bloody battle, Porus was defeated, though Alexander, impressed by Porus’s bravery and leadership, reinstated him as a satrap and granted him additional territories.

4.3 March Towards the Beas River and Retreat

Following his victory over Porus, Alexander continued his march eastward toward the Beas River, which marked the furthest extent of his advance into India. By this point, Alexander had been campaigning for nearly eight years, and his troops were exhausted. The Indian subcontinent presented formidable challenges, not only in terms of geography and climate but also in the form of powerful kingdoms such as Magadha, ruled by the Nanda dynasty.

Upon hearing of the Nanda Empire’s vast army, which was said to number over 200,000 infantry and thousands of war elephants, Alexander’s troops began to lose their enthusiasm for further conquests. Despite his personal desire to push on and conquer the rest of India, Alexander faced a mutiny from his army, which refused to march any further. Reluctantly, Alexander agreed to turn back and begin the long journey home.

4.4 Alexander’s Return and Death

After reaching the Beas River, Alexander and his army retraced their steps, sailing down the Indus River and encountering fierce resistance from various tribal groups along the way, including the Malli and Sambastai tribes. The retreat was a difficult and costly endeavor, with many of Alexander’s soldiers succumbing to disease, desertion, and hostile attacks.

In 324 B.C., Alexander returned to Babylon, where he made plans to consolidate his empire and launch new campaigns. However, these plans were cut short by his sudden death in 323 B.C., at the age of 32. Alexander’s death led to the fragmentation of his empire, with his generals, known as the Diadochi, carving up his territories among themselves. The territories in India came under the control of Seleucus Nicator, one of Alexander’s leading generals.

5. Impact of the Macedonian Invasions on India

5.1 Political Impact of Alexander’s Invasion

Although Alexander’s invasion of India was short-lived, it had significant political consequences for the region. The most immediate impact was the disruption of the existing power structures in northwestern India. Several local rulers, including Ambhi of Taxila and Porus, were either displaced or co-opted into the Macedonian administrative system, which temporarily extended Alexander’s influence over the region.

However, the most important long-term political impact of Alexander’s invasion was the opening of the northwest frontier to future invasions and migrations. After Alexander’s death, the power vacuum he left in the region allowed for the rise of new foreign powers, including the Indo-Greeks, Sakas, Parthians, and Kushanas, all of whom would establish control over parts of northwestern India.

The invasion also weakened the existing Indian states, making it easier for Chandragupta Maurya to conquer the region and establish the Mauryan Empire. Alexander’s departure marked the end of Greek political influence in India, but it set the stage for the rise of a powerful and unified Indian state under the Mauryas.

5.2 Economic Impact: Expansion of Trade Routes

One of the most significant consequences of Alexander’s invasion was the expansion of trade routes between India and the Mediterranean world. During his campaigns, Alexander established new trade connections between India, Persia, and Greece, facilitating the exchange of goods, ideas, and technologies. Greek merchants, artisans, and scholars traveled to India, while Indian goods such as spices, textiles, and precious stones were exported to the Mediterranean.

This increased trade and interaction between the West and East contributed to the development of new economic networks that would continue to flourish in the centuries to come. These trade routes helped introduce Greek coinage, artistic styles, and scientific knowledge to India, while Indian philosophy, religion, and mathematics began to influence the Mediterranean world.

5.3 Cultural Impact: The Spread of Hellenism

Alexander’s invasion also introduced elements of Hellenistic culture to India. Although his direct influence was short-lived, the Indo-Greek kingdoms that arose after his death helped spread Greek art, architecture, and philosophy throughout northwestern India. This cultural exchange is most evident in the Gandhara School of Art, which combined Greek, Persian, and Indian influences to create a unique artistic style.

Greek influence on Indian art is particularly evident in Buddhist sculpture, where Hellenistic techniques were used to depict religious figures such as the Buddha. Greek motifs, including Corinthian columns, fluted pillars, and realistic depictions of the human form, became integrated into Indian architecture and sculpture.

This cultural fusion, known as Greco-Buddhism, would have a lasting impact on the artistic traditions of India, particularly in the northwestern regions. The Gandhara style of Buddhist art, which flourished under the Kushana Empire, is a testament to the enduring legacy of Greek influence in Indian culture.

5.4 Greek Influence on Indian Governance and Military Tactics

One of the most important consequences of Alexander’s invasion was the introduction of Greek military tactics and strategies to the Indian subcontinent. The Greeks were known for their highly disciplined phalanx formations and the use of combined arms, including cavalry, infantry, and siege weapons. These tactics, while not entirely new to India, influenced Indian rulers, particularly those in the northwest, who had the most direct contact with the Greeks.

The Mauryan Empire, founded by Chandragupta Maurya, benefited from this exchange of military knowledge. According to historical accounts, Chandragupta Maurya was inspired by the administrative and military organization of the Greeks, which he encountered both during and after Alexander’s invasion. The Mauryan army, which was the largest standing army of its time, incorporated elements of Greek military organization, including the use of war elephants, cavalry, and siege technology.

The Indo-Greek rulers who succeeded Alexander’s generals in the northwestern territories of India also brought with them Greek military traditions, which continued to shape the region’s defenses and military strategies. Greek-style fortifications, barracks, and military outposts were established in these regions, contributing to the defense of the northwest frontier against subsequent invasions by the Sakas and Kushanas.

5.5 Greek Influence on Indian Philosophy and Science

In addition to military and administrative influences, Alexander’s invasion facilitated an exchange of philosophical and scientific ideas between Greece and India. During his campaigns, Alexander encountered Indian sages, known as gymnosophists, who practiced a form of asceticism and philosophy that intrigued the Greek conqueror and his scholars. These Indian philosophers were well respected by the Greeks, and their ideas about metaphysics, ethics, and the nature of the universe influenced Greek thought, particularly in the Hellenistic period.

Similarly, Indian astronomy and mathematics influenced Greek scholars who traveled to India following Alexander’s campaigns. Indian knowledge of celestial movements, geometry, and arithmetic was of great interest to the Greeks, who incorporated some of these concepts into their own scientific systems. The exchange of knowledge between India and the Hellenistic world laid the foundation for further advancements in science and philosophy in both regions.

One prominent example of this cultural exchange was the development of Indian astronomy, which was influenced by Greek theories about the motion of the stars and planets. The Indo-Greek kings who ruled in the northwest continued this exchange, sponsoring the work of Indian and Greek astronomers who collaborated to create astronomical texts that influenced both the Indian and Mediterranean worlds.

5.6 Greek Influence on Indian Coinage

The influence of Alexander’s invasion is perhaps most evident in the area of Indian coinage. The Greek practice of minting coins with portraiture and Hellenistic motifs was introduced to India by the Indo-Greek rulers, who struck coins that featured images of Greek gods, rulers, and symbols. These coins were used as currency in the northwestern territories of India and helped facilitate trade and commerce with the wider Mediterranean world.

Before Alexander’s invasion, Indian coinage was relatively simple and often featured geometric shapes or animal motifs. After the arrival of the Greeks, Indian rulers began to adopt more refined techniques for producing coins, including the use of metal dies and engraved images. The Indo-Greek coins, which often featured the faces of Greek rulers on one side and Indian symbols or deities on the other, symbolized the cultural and political fusion that occurred in the region.

These coins not only facilitated trade but also served as a means of political propaganda, showcasing the power and legitimacy of Indo-Greek rulers. The influence of Greek coinage on Indian minting practices can be seen throughout the history of the Mauryan Empire and beyond, with later Indian dynasties adopting similar techniques for producing currency.

5.7 Greek-Roman Accounts of India: Early Observations

The Greek-Roman accounts of India, particularly those written by historians and scholars who accompanied Alexander during his campaigns, provide some of the earliest documented observations of Indian society, culture, and geography. These accounts, which were recorded by Greek historians such as Arrian, Strabo, and Plutarch, offer valuable insights into the Indian subcontinent during the late 4th century B.C..

One of the most famous accounts is that of Megasthenes, a Greek ambassador who lived at the court of Chandragupta Maurya in the capital city of Pataliputra. In his work Indika, Megasthenes described Indian society, its caste system, governance, and economic practices. His observations on Indian agriculture, trade, and the Indian military provide an invaluable historical record of ancient India and its relationship with the Greek world.

Megasthenes’ account also sheds light on the religious practices of India, particularly the growing influence of Buddhism and Jainism. He noted the ascetic practices of Indian sages and the reverence for animals, which contrasted sharply with Greek religious practices. His writings contributed to the Greek fascination with Indian philosophy and laid the groundwork for further cultural exchanges between the two civilizations.

5.8 Greek and Roman Descriptions of Indian Geography and Trade

The geography of India, as described by Greek and Roman historians, played a crucial role in shaping Western perceptions of the Indian subcontinent. Herodotus, Pliny the Elder, and other classical writers provided detailed descriptions of the Indian landscape, its rivers, mountain ranges, and coastlines. These descriptions, while often exaggerated or based on second-hand accounts, contributed to the growing body of geographical knowledge about the Indian Ocean region.

The Indus River, in particular, was seen as a critical waterway that connected India with Persia and the Mediterranean world. The exploration of the Indus by Scylax of Caryanda, who was commissioned by Darius I to survey the river, helped establish maritime trade routes between India and Persia. These trade routes were later expanded by the Greeks and Romans, who established commercial networks that connected India to Alexandria, Athens, Rome, and other Mediterranean cities.

Greek and Roman writers were also fascinated by the luxury goods produced in India, particularly its spices, silk, precious stones, and ivory. These goods were highly sought after in the Roman Empire, and trade with India became a major source of wealth for both Indian and Roman merchants. Pliny the Elder lamented the high cost of importing luxury goods from India, noting that Rome was sending vast sums of gold and silver to the East in exchange for these items.

The trade between India and the Roman Empire, facilitated by Greek maritime knowledge, helped integrate the Indian subcontinent into the global economy of the ancient world. Roman coins have been found in large quantities in southern India, indicating the extensive nature of the trade routes that linked the two civilizations.

5.9 Greek Influence on Indian Astronomy and Mathematics

The Greek influence on Indian science is particularly evident in the fields of astronomy and mathematics. The Greeks, known for their advancements in astronomical observation and geometrical theories, introduced their knowledge to India, where it was integrated with existing Indian traditions. Greek astronomical models, particularly the Ptolemaic system, were studied and adapted by Indian scholars, who combined them with their own observations of the stars and planets.

The result of this exchange was the development of a highly sophisticated Indian astronomical tradition, which would later influence Islamic and European scholars during the Middle Ages. Indian mathematicians, such as Aryabhata and Brahmagupta, built on Greek mathematical concepts, particularly in the areas of geometry and trigonometry, to develop their own groundbreaking theories.

Indian scholars also contributed to the study of celestial movements, refining Greek models and making significant contributions to the understanding of planetary motion. The influence of Greek mathematics is evident in the use of Greek-derived terms in Indian astronomical texts, as well as the incorporation of Greek geometrical methods into Indian calculations of eclipses and planetary orbits.

5.10 Long-Term Cultural Impact: Indo-Greek and Indo-Roman Synthesis

The Indo-Greek Kingdoms, established in the wake of Alexander’s invasion, played a crucial role in the long-term cultural exchange between Greece, Rome, and India. These kingdoms, which existed in the northwestern regions of India for nearly two centuries, became centers of Hellenistic culture in India. Greek rulers in these regions adopted Buddhism and sponsored the construction of Buddhist stupas, while Indian artisans incorporated Greek artistic motifs into their works.

The cultural fusion that occurred in the Indo-Greek period laid the foundation for the development of the Gandhara School of Art, which flourished under the Kushana Empire. This school of art is renowned for its realistic depictions of the human form, which were inspired by Greek naturalism, and its use of Greek architectural elements, such as Corinthian columns and draped clothing. The Gandhara-style Buddha statues, with their distinctive Hellenistic features, are perhaps the most iconic example of this cultural synthesis.

The Indo-Roman trade, which flourished during the first century A.D., further contributed to the cultural exchange between India and the Mediterranean world. Roman traders established settlements in southern India, and Roman coins circulated widely throughout the region. The Indian Ocean trade routes, which connected India with the Roman Empire, brought Roman glassware, wine, and luxury goods to India, while Indian spices, pearls, and textiles were exported to Rome.

This long-term exchange of goods, ideas, and cultural practices between India, Greece, and Rome had a profound impact on the development of Indian civilization. Greek philosophical concepts, artistic styles, and scientific knowledge were integrated into Indian thought, while Indian religions, trade goods, and technologies spread to the Mediterranean world.

5.11 Influence on Religious and Philosophical Thought

The Macedonian invasion and subsequent Greek presence in India had a profound impact on religious and philosophical thought in the region. Although Alexander’s stay in India was brief, his conquest and the Indo-Greek rule that followed introduced new perspectives that merged with existing Indian traditions. This influence can be seen most notably in the development of Buddhism and Hellenistic philosophical ideas.

After the establishment of the Indo-Greek kingdoms, many Indo-Greek rulers, including Menander I, embraced Buddhism. Menander I, also known as Milinda, is famously depicted in the Buddhist text Milinda Panha (The Questions of Milinda), where he engages in a philosophical dialogue with the Buddhist sage Nagasena. This interaction highlights the blending of Greek logic and dialectical methods with Indian spiritual and religious concepts. Menander’s conversion to Buddhism and his patronage of Buddhist institutions fostered the spread of Buddhism in northwestern India and beyond.

The Greco-Buddhist exchange led to the flourishing of Greco-Buddhist philosophy, where elements of Greek rationalism and ethical inquiry were fused with Buddhist ideas of karma, nirvana, and moral living. This fusion enriched both Buddhist philosophy and Hellenistic thought, creating a unique form of cross-cultural dialogue. The result was the development of new forms of Buddhist scholasticism that would later spread across Central Asia, China, and Southeast Asia.

Additionally, the Hellenistic philosophical traditions—such as Stoicism and Epicureanism—influenced Indian religious thinkers, particularly in their emphasis on ethics and the nature of human happiness. This synthesis of ideas contributed to the intellectual ferment that characterized early Buddhist and Jain monastic schools in the northwestern regions of India. The interaction between Indian asceticism and Greek philosophical inquiry helped to shape religious thought in India and beyond, further cementing the Indo-Greek cultural legacy.

5.12 The Gandhara School of Art and Greco-Buddhist Art

One of the most visible and lasting legacies of the Greek presence in India is the Gandhara School of Art, a form of Greco-Buddhist art that emerged in the northwestern regions of the subcontinent. This artistic movement, which flourished during the reign of the Kushana Empire (circa 1st to 3rd centuries A.D.), is considered a fusion of Hellenistic, Persian, and Indian artistic traditions.

The Gandhara School is best known for its sculptures of the Buddha, which display clear Greek influences in their naturalistic style, realistic anatomy, and use of draped clothing that mimics the Hellenistic art of the Mediterranean world. The Buddha statues produced by the Gandhara artists were among the first depictions of the Buddha in human form. These sculptures often feature Greek artistic techniques, such as the use of contrapposto (a natural stance) and realistic facial expressions, which were not common in earlier Indian art.

The architectural elements of the Gandhara School also reflect the Hellenistic influence, with the use of Corinthian columns, elaborate friezes, and ornate capitals. Temples and monasteries built during this period often featured Greek-style porticoes and pediments, further demonstrating the cross-cultural exchange between Greece and India. The widespread construction of stupas and monasteries in the Gandhara region helped promote the spread of Buddhism, particularly along the Silk Road and into Central Asia.

The Gandhara School also influenced the later development of Buddhist art in China, Korea, and Japan, where elements of the Greek-inspired depiction of the Buddha can still be seen. This Greco-Buddhist artistic legacy continued to shape the religious and artistic traditions of Asia for centuries, making the Gandhara School of Art one of the most important cultural outcomes of the Macedonian invasion of India.

5.13 The Indo-Greek Kingdoms and Their Role in Indian History

Following Alexander’s invasion and the fragmentation of his empire, several of his generals and successors established Indo-Greek kingdoms in northwestern India. The most prominent of these kingdoms was the Greco-Bactrian Kingdom, which extended from Bactria (modern-day Afghanistan) into the Indian subcontinent. The Indo-Greek rulers played a significant role in shaping the political and cultural landscape of northwestern India for nearly two centuries.

These Indo-Greek rulers maintained close diplomatic and trade relations with both Hellenistic states in the west and Indian kingdoms in the east. The most famous of these rulers, Menander I, expanded Indo-Greek control into the Punjab and parts of northern India, creating a powerful and wealthy kingdom. Menander’s conversion to Buddhism and his role as a patron of Buddhist institutions is one of the most significant aspects of his reign, as it facilitated the spread of Buddhism along the Silk Road.

The Indo-Greek kingdoms also played a key role in the transmission of Greek knowledge, particularly in the areas of astronomy, medicine, and mathematics, to the Indian subcontinent. Greek medical practices and theories, such as those found in the works of Hippocrates and Galen, influenced Indian medical traditions, while Greek advancements in astronomy contributed to the development of Indian scientific thought.

Politically, the Indo-Greek kingdoms were significant for their role in defending the northwestern frontiers of India against nomadic invasions from Central Asia. The Indo-Greeks were involved in constant conflict with the Sakas, Parthians, and Yuezhi, who sought to invade and settle in the fertile regions of the Indus Valley. While the Indo-Greek kingdoms eventually fell to these invaders, their legacy endured through their contributions to Indian culture, art, and science.

5.14 Indo-Roman Trade Relations: A Flourishing Economic Exchange

In the centuries following Alexander’s invasion, trade between India and the Roman Empire flourished, largely due to the maritime routes and land routes established during the Hellenistic period. The Roman demand for Indian goods, particularly spices, silk, ivory, and pearls, created a vibrant Indo-Roman trade network that linked the Mediterranean world with the Indian subcontinent.

Roman merchants sailed across the Red Sea and along the Arabian coast, trading goods in Indian ports such as Muziris, located on the Malabar Coast in southern India. Indian goods, particularly pepper and silk, were highly prized in Rome, where they were considered luxury items. Roman goods, such as wine, glassware, and metalwork, were exchanged for these Indian exports, enriching both Roman and Indian merchants.

Roman coins, which have been found in large quantities in southern India, provide evidence of the extensive commercial exchanges between the two regions. These coins were used as currency in Indian markets, demonstrating the integration of the Indian economy into the Roman monetary system. The Roman presence in India also left its mark on Indian art and architecture, as seen in the Roman-style amphorae and other Mediterranean influences found in Indian archaeological sites.

The Indo-Roman trade network was not limited to the exchange of goods but also facilitated the cultural exchange of ideas, technologies, and religious practices. Roman merchants who settled in India brought with them elements of Roman culture, including Hellenistic art, Roman law, and Western philosophical ideas. Likewise, Indian religious and philosophical concepts, particularly those associated with Buddhism, traveled westward, influencing religious thought in the Roman Empire.

The flourishing Indo-Roman trade relations not only contributed to the wealth and prosperity of southern Indian kingdoms, such as the Cheras, Cholas, and Pandyas, but also helped establish India as a key player in the global economy of the ancient world. This economic exchange continued until the decline of the Roman Empire in the 5th century A.D., but the cultural and commercial connections that were established during this period had a lasting impact on the development of both Indian and Mediterranean civilizations.

5.15 The Decline of Greek Influence in India

The decline of Greek influence in India began with the gradual weakening of the Indo-Greek kingdoms and the rise of new powers in the region. By the 1st century B.C., the Indo-Greek kingdoms were increasingly under pressure from Central Asian nomadic tribes, including the Sakas, Parthians, and Yuezhi, who began to invade and settle in the Indus Valley. The Indo-Greek rulers were eventually overthrown by the Kushanas, a nomadic tribe that established a powerful empire in northwestern India.

Despite the decline of Greek political control in the region, the cultural and intellectual legacy of the Greeks continued to influence Indian society. The Gandhara School of Art remained a vibrant artistic tradition, and the Greco-Buddhist synthesis continued to shape the development of Buddhist philosophy and art in Central Asia and China. Greek astronomical and medical knowledge also remained influential in Indian scholarly circles, contributing to the continued advancement of Indian science.

The legacy of Alexander the Great’s invasion and the subsequent Indo-Greek period was one of cultural fusion, intellectual exchange, and artistic innovation. While the Greek presence in India was relatively short-lived, its impact on Indian civilization was profound and long-lasting, influencing everything from art and philosophy to trade and political organization.

6. Greek-Roman Accounts on India

6.1 Early Greek-Roman Descriptions of India

The Greek-Roman interest in India began well before Alexander’s invasion, with Herodotus (5th century B.C.) providing early descriptions of India. Herodotus, often called the “Father of History,” provided accounts of India’s fertility, wealth, and gold reserves, though much of his information was based on hearsay and speculation. He described India as a land of vast riches, inhabited by people who wore cotton garments and worshipped a variety of gods.

The exploration of the Indus River by Scylax of Caryanda under Darius I is another early reference to India in Greek writings. Scylax’s accounts contributed to the geographical knowledge of the Greeks about India’s rivers and the routes leading to it. Later, Megasthenes, who was sent as an ambassador by Seleucus Nicator to the court of Chandragupta Maurya, provided the most comprehensive Greek account of India in his work, Indika. He described India’s geography, society, religious practices, and government.

6.2 Megasthenes’ Indika: A Greek View of Indian Society

Megasthenes is a key source of Greek information about India. His work, Indika, though lost, is preserved in fragments through later writers such as Strabo, Arrian, and Diodorus Siculus. Megasthenes’ observations were crucial because they offered a detailed account of Mauryan India around 300 B.C. He described Pataliputra, the capital of the Mauryan Empire, as a magnificent city with high walls and well-planned streets, reflecting the advanced urban planning of the time.

Megasthenes provided detailed descriptions of Indian caste divisions, with particular attention to the Brahmins and Kshatriyas, the priestly and warrior classes, respectively. He observed the Brahmins’ religious rituals, their ascetic lifestyle, and their profound influence on Indian society. His account of the Nandas and their vast army is particularly notable, as it highlights the military strength and organizational skills of the Mauryan rulers.

Megasthenes also noted the Indian legal system, which he described as simple yet effective, with a heavy emphasis on moral conduct and personal ethics. According to Megasthenes, the Indians were an honest people, rarely resorting to theft or deceit, a trait he greatly admired.

6.3 Roman Accounts of India

As Roman trade with India expanded, Roman writers began to take a greater interest in the subcontinent. Pliny the Elder, in his work Naturalis Historia, provided detailed descriptions of India, emphasizing its wealth and abundant resources. He lamented the drain of Roman wealth to India due to the high demand for Indian luxury goods, especially spices, silk, and precious stones. Pliny’s accounts highlight the importance of India in the global economy of the ancient world and the crucial role played by Indo-Roman trade routes.

Roman interest in India was primarily driven by economic considerations. The Periplus of the Erythraean Sea, an important Roman maritime guide, described the sea routes between the Roman Empire and India, detailing the various ports and commodities involved in the lucrative Indo-Roman trade. This text offers valuable insights into the commercial exchanges that took place between the Mediterranean world and India during the first centuries of the Common Era.

6.4 Impact of Greek and Roman Writings on Indian History

The Greek and Roman writings about India, though sometimes inaccurate, have provided historians with critical information about ancient India’s economy, society, and culture. These accounts, particularly those of Megasthenes, Herodotus, Pliny, and others, helped shape Western perceptions of India for centuries. They also serve as important historical documents for understanding the extent of Indo-Greek and Indo-Roman interactions, the economic importance of India in the ancient world, and the cultural exchanges that took place between the East and West during this period.

The chronological information provided by Greek historians, especially regarding Alexander’s campaigns, is essential for reconstructing the timeline of events in Indian history, such as the fall of the Achaemenid Empire and the subsequent rise of the Mauryan dynasty. This cross-cultural exchange left an enduring legacy in the form of Greek philosophical influence, scientific exchanges, and artistic traditions that continued to shape Indian culture long after the departure of the Indo-Greek rulers.

6.5 The Role of Geography in Greek-Roman Understanding of India

Greek and Roman accounts of India often focused on its geographical features, particularly its rivers, mountain ranges, and fertile plains. The Indus River was frequently mentioned in Greek texts, as it was one of the first regions of India to come under Persian and later Macedonian control. The Ganges River, which was known to the Greeks through indirect sources, was described as one of the great rivers of the world, comparable in majesty to the Nile or the Danube.

Greek geographers, such as Strabo and Ptolemy, attempted to map India based on the information available from explorers and merchants who had traveled to the subcontinent. While these maps were often inaccurate, they reflect the growing Greek and Roman interest in understanding India’s geography and economic potential.

In addition to its rivers, India’s natural resources—particularly its spices, pearls, and gold—were of immense interest to Roman writers. Pliny the Elder’s accounts of Indian forests, wildlife, and mineral wealth contributed to the Roman view of India as a land of abundance and luxury.

7. Chronology of Foreign Invasions of India

- 518-486 B.C. – King Darius I or Darus Invades India

- Darius I, the ruler of the Achaemenid Empire, extended his empire into northwestern India, including Gandhara, Sindh, and Punjab. His conquest integrated these regions into the Persian Empire.

- 326 B.C. – Alexander the Great Invades India

- Alexander the Great launched his campaign into India after defeating Darius III of Persia. His invasion primarily affected the northwestern part of India, where he fought against King Porus in the Battle of Hydaspes. After his death, his generals established the Indo-Greek kingdoms in the region.

- 190 B.C. – Indo-Greeks or Bactrians Invade India

- The Indo-Greeks, descendants of the Bactrian Greeks who were part of Alexander’s empire, established kingdoms in northwestern India. They ruled significant portions of Gandhara and the Punjab and played a major role in the spread of Hellenistic culture in the region.

- 90 B.C. – Sakas Invade India

- The Sakas, also known as the Scythians, invaded northwestern India. They displaced the Indo-Greek rulers and established their own rule. The Sakas later became influential in western and northern India, particularly in Gujarat and Malwa.

- 1st Century A.D. – Pahalavas Invade India

- The Pahalavas, also known as the Parthians, invaded India and established their control over parts of northwestern India. Their influence was mostly seen in Gandhara and Sindh.

- 45 A.D. – Kushanas or Yue-chis Invade India

- The Kushanas, originally from Central Asia, invaded India around 45 A.D. and established a large empire in northern India. The Kushana Empire, under rulers such as Kanishka, became a major power and played a crucial role in the spread of Buddhism across Central Asia.

[…] Iranian and Macedonian Invasions of India and Their Impact […]

[…] Iranian and Macedonian Invasions of India and Their Impact […]