January 25, 2026 4:29 am

Table of Content

- Historical Sources for the Study of the Mahajanapadas (c. 600–300 BCE)

- Transition from Janas to Janapadas: The Formation of Mahajanapadas

- The Mahajanapadas: Monarchies and Republics

- Political and Military Conflicts Among the Mahajanapadas

- 4.1 Rivalries Between Monarchies

- 4.2 The Decline of Republics

- 4.2.1 Internal Conflicts and Fragmentation

- 4.2.2 Limited Resources and Military Capability

- 4.2.3 External Threats and Conquests by Monarchies

- 4.2.4 The Role of Diplomacy and Alliances

- 4.2.5 Shift in Political Ideology: From Oligarchy to Monarchy

- 4.2.6 Absence of Strong Leadership

- 4.2.7 The Decline of Republican Institutions

- 4.2.8 Economic Decline

- 4.2.9 Religious Influence and the Shift Toward Centralization

- 4.2.10 The Absorption of Republics into Larger Empires

- 5. The Mahajanapadas: Overview of Key States

- 5.1 Magadha: The Most Powerful Mahajanapada

- 5.2 Kosala: The Rival of Magadha

- 5.3 Vatsa: A Kingdom of Trade and Diplomacy

- 5.4 Avanti: A Regional Power in Western India

- 5.5 Vajji: The Prominent Republican Confederacy

- 5.6 Malla: The Significant Republican State

- 5.7 Kashi: The Kingdom of Religious and Commercial Importance

- 5.8 Kuru: The Decline of a Vedic Power

- 5.9 Panchala: The Transition to a Republic

- 5.10 Surasena: A Monarchy with Strategic Importance

- 5.11 Vajji: A Powerful Republican Confederacy

- 5.12 Kamboja: A Frontier State

- 5.13 Assaka: The Southernmost Mahajanapada

- 5.14 Matsya: A Lesser-Known Mahajanapada

- 6. The Decline and Absorption of the Mahajanapadas

- 6.1 The Rise of Magadha as the Dominant Power

- 6.2 The Role of Geography and Resources in the Rise of Magadha and Decline of other Mahajanapadas

- 6.3 The Integration of the Mahajanapadas into the Mauryan Empire

- 6.4 The Influence of Religion on the Mahajanapadas and Their Integration

- 6.5 The Transition from Regional Powers to a Pan-Indian Empire

- 6.6 The Legacy of the Mahajanapadas in Indian History

- 7. The Political Structures of the Mahajanapadas

- 8. The Military Organization of the Mahajanapadas

- 9. Economic Foundations of the Mahajanapadas

- 9.3 Urbanization and the Growth of Cities

- 9.4 Taxation and State Revenue

- 9.5 Role of Iron in Economic Growth

- 10. Religious and Cultural Developments in the Mahajanapada Period

- 11. Conclusion: The Mahajanapadas and the Foundations of Indian Civilization

- MCQs

- Mains Questions

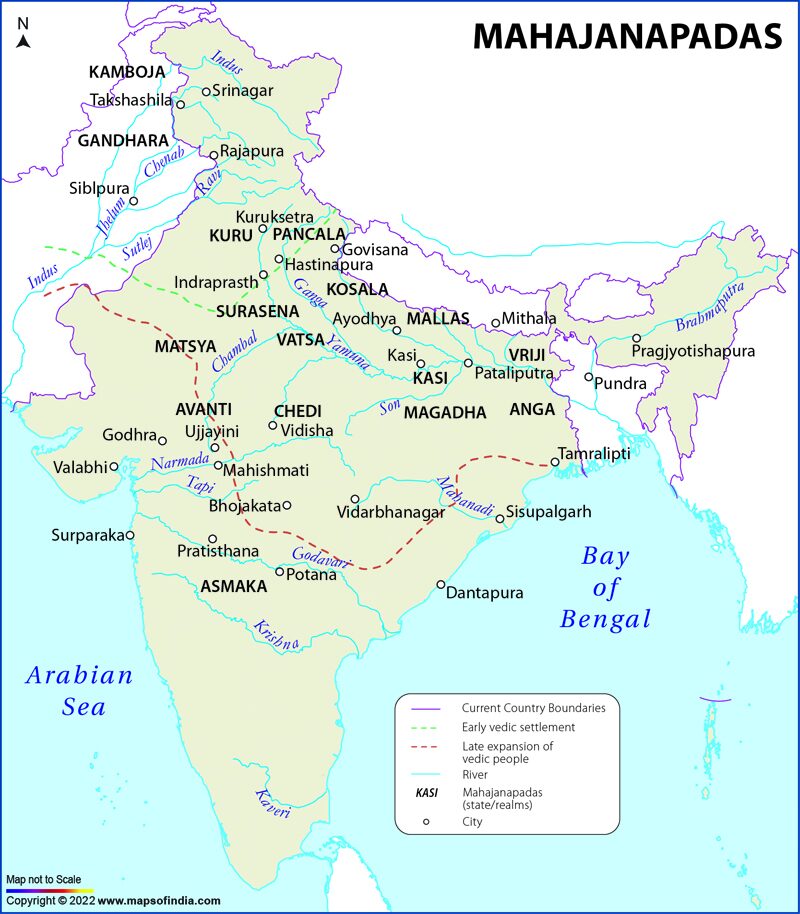

The 6th century BCE marks a crucial period in the political history of ancient India, as it witnessed the rise of the Mahajanapadas—great territorial states. These Mahajanapadas were instrumental in shaping India’s early political structures, which included both monarchies and republics. As these states evolved, they laid the foundation for future Indian empires. This detailed exploration will dive into the origins, governance, and conflicts of the Mahajanapadas, with a focus on the sources of historical evidence, the distinctions between monarchies and republics, and the significance of the era.

Historical Sources for the Study of the Mahajanapadas (c. 600–300 BCE)

1. Buddhist Texts

The Buddhist texts, particularly the Pali canon, provide invaluable insights into the history of the Mahajanapadas. These texts include the Sutta Pitaka, composed between the 5th and 3rd centuries BCE, which offers detailed information about the political dynamics of the time. Important texts like the Digha Nikaya, Majjhima Nikaya, Samyutta Nikaya, and the Vinaya Pitaka illuminate the social, religious, and political milieu of the Mahajanapadas. The Jatakas—a collection of stories within the Pali canon—though often used as historical references, are generally placed in a later period (3rd century BCE–2nd century CE). They should be utilized with caution when reconstructing the events of the 6th century BCE, as they primarily reflect the values and beliefs of the time in which they were compiled rather than the earlier periods they describe.

2. Brahmanical Texts

The Brahmanical texts, especially the Puranas, offer details on dynastic history. However, these texts often present challenges due to the contradictions in dynastic lists and conflicting accounts of rulers. For example, the Puranas sometimes mix up rulers from different lineages and present contemporaneous kings as successors. While these texts provide valuable information on the genealogies of the Mahajanapadas, they must be critically analyzed and cross-referenced with other sources to ensure accuracy.

Another important source is the Grihyasutras and Dharmasutras. These early legal texts, composed around the same time as the emergence of the Mahajanapadas, provide insights into the social norms, legal structures, and rituals of the time. These texts reflect the Brahmanical perspective on governance and society.

Panini’s Ashtadhyayi, a 5th century BCE Sanskrit grammar text, offers additional valuable information. Although primarily a grammatical work, Panini references numerous places, customs, and institutions, thus providing historians with a detailed snapshot of life during the rise of the Mahajanapadas.

3. Jaina Texts

The Jaina texts, such as the Bhagavati Sutra and the Parishishtaparvan, provide an alternative perspective on the Mahajanapadas, supplementing information from Buddhist and Brahmanical sources. These texts describe the political, social, and religious contexts of the time, with an emphasis on non-violence and moral governance, which were central to Jaina philosophy.

4. Foreign Sources

Greek and Latin accounts of Alexander’s invasion of India (327–326 BCE) are another important source for the study of the Mahajanapadas. Writers such as Arrian, Curtius Rufus, Plutarch, and Justin provide descriptions of the political landscape of north-western India. These accounts focus on the Gandhara and Kamboja regions, describing their governance systems and military strategies during Alexander’s campaign.

5. Archaeological Evidence

Archaeological findings, particularly those associated with the Northern Black Polished Ware (NBPW) culture, shed light on the material culture and urbanization of the Mahajanapadas. The NBPW phase is dated between the 7th and 2nd centuries BCE, and excavations at sites such as Rajghat and Chirand have revealed important artifacts, including punch-marked coins. These coins represent one of the earliest forms of currency in the Indian subcontinent and indicate the growing sophistication of the Mahajanapadas’ economies.

The widespread use of iron during this period, particularly in eastern Uttar Pradesh and western Bihar, also contributed to the expansion of agriculture and military power, both of which were crucial to the development of large territorial states.

Transition from Janas to Janapadas: The Formation of Mahajanapadas

2.1 The Evolution of Tribal States into Territorial Kingdoms

In the early Vedic period, society was organized into tribal units known as Janas. These tribes were semi-nomadic and frequently engaged in conflicts over pastures and cattle. However, as these tribes began to settle in specific regions, they gradually formed territorial states known as Janapadas. The term Janapada literally means “foothold of a tribe,” reflecting the tribe’s claim over a particular area of land.

By the time of Gautama Buddha and Panini in the 6th century BCE, this process had led to the emergence of Mahajanapadas—large territorial states that marked the final stage of the transition from a nomadic to a settled society. Each Janapada was named after the tribe that had initially settled there, such as Kuru, Panchala, Vatsa, and Magadha.

2.2 The Role of Iron and Economic Growth

The widespread use of iron during this period played a crucial role in the rise of the Mahajanapadas. Iron tools made agricultural expansion easier, allowing farmers to clear forests and cultivate more land. This led to greater agricultural surpluses, which supported the growth of urban centers and facilitated trade. Major cities like Rajagriha, Champa, Shravasti, Ayodhya, Kashi, and Pataliputra became important hubs of industry and commerce, further strengthening the economic and military power of the Mahajanapadas.

The Mahajanapadas: Monarchies and Republics

The political organization of the Mahajanapadas was diverse, with some states developing into monarchies while others became republics (or Ganas and Sanghas). The differences in governance are significant, with monarchies centralizing power in a single ruler, while republics distributed power among an assembly of elites.

3.1 Monarchical States

Most of the Mahajanapadas were monarchies, where power was concentrated in the hands of a king or ruler. The Brahmanical texts, such as Kautilya’s Arthashastra, describe the components of these monarchies using the Saptanga theory, which identifies the seven essential elements of the state: the king, the minister, the territory, the fortified city, the treasury, the army, and the ally.

3.1.1 Magadha: The Most Powerful Monarchy

The kingdom of Magadha, located in present-day Bihar, was the most powerful Mahajanapada. Under the leadership of kings like Bimbisara and Ajatashatru, Magadha expanded its territory through conquests and alliances. The kingdom’s strategic location on the Gangetic plains, combined with its access to iron resources, gave it a significant advantage over its rivals.

Bimbisara, the ruler of Magadha, is credited with building alliances through marriage and annexing neighboring states like Anga. His son, Ajatashatru, continued his father’s expansionist policies, defeating the Vajjis and incorporating their territory into Magadha.

3.1.2 Kosala and Avanti

Other prominent monarchies during this period were Kosala and Avanti. Kosala, with its capital at Ayodhya, was ruled by King Prasenjit during the time of Buddha. Avanti, with its capital at Ujjain, was another powerful kingdom. Both of these states were engaged in constant warfare and diplomatic negotiations to expand their influence and control over the Ganga-Yamuna doab.

3.2 Republican States: Ganas and Sanghas

In contrast to the monarchies, several Mahajanapadas were organized as republics, where power was vested in an assembly or council rather than a single ruler. These states were known as Ganas or Sanghas. Some notable examples include:

- Vajji (Vrijji): The Vajji confederacy, with its capital at Vaishali, was one of the most prominent republican states. The Vajji assembly, which was composed of 7707 rajas, governed the state through a decentralized political system, where decisions were made collectively by the ruling elite.

- Malla: The Mallas were another prominent republican state. Their territory, located in present-day eastern Uttar Pradesh, is notable for its association with Buddhism. The town of Kusinara, where Buddha attained Mahaparinirvana, was located within the Malla territory.

- Sakyas: The Sakya republic, with its capital at Kapilavastu, is historically significant as the birthplace of Gautama Buddha. The Sakya assembly governed through a system of shared leadership, with decision-making powers vested in the council.

3.3 Republics and Oligarchies: Governance in the Ganas and Sanghas

While the Ganas and Sanghas are often referred to as republics, their political systems were more akin to oligarchies. In these states, power was concentrated in the hands of a small group of elite families, typically Kshatriyas, who governed through an assembly. The general population, including women and lower-caste individuals, had no role in the decision-making process. As a result, the republican states were not democratic in the modern sense but were instead controlled by a small, aristocratic class.

Political and Military Conflicts Among the Mahajanapadas

4.1 Rivalries Between Monarchies

The 6th century BCE was a period of intense rivalry among the Mahajanapadas, particularly between the monarchies of Magadha, Kosala, Vatsa, and Avanti. These states frequently engaged in military conflicts to expand their territories and secure control over trade routes and agricultural lands.

Magadha’s rise to power under Bimbisara and Ajatashatru was marked by its conquest of neighboring states like Anga. Magadha’s eventual annexation of Kosala further solidified its dominance in the region.

4.2 The Decline of Republics

While the republican states were initially successful in maintaining their independence, they gradually weakened in the face of rising monarchies. Internal divisions, limited resources, and the absence of a centralized military made these republics vulnerable to conquest by more powerful monarchies like Magadha.

4.2.1 Internal Conflicts and Fragmentation

One of the primary reasons for the decline of the republican states was internal conflicts. Unlike monarchies, where a single ruler could unify the state, republics often struggled with disagreements and power struggles among the ruling elite. The Ganas or Sanghas (assemblies) of these republics consisted of multiple Kshatriya clans, and decisions were made collectively. While this ensured that power was distributed, it also made decision-making slow and inefficient. As rival clans vied for control, internal divisions weakened the republics’ ability to respond to external threats.

In many cases, the republican states were unable to maintain a unified front against the powerful monarchies that surrounded them. For example, in Vajji, one of the most well-known republican states, the ruling clans were often at odds with one another. These internal disputes made it difficult to mount a coordinated defense when Magadha under Ajatashatru invaded and eventually conquered the Vajji confederacy.

4.2.2 Limited Resources and Military Capability

Another factor that contributed to the decline of the republics was their limited resources. Unlike the monarchies, which controlled large agricultural lands and commanded extensive armies, the republics often had fewer economic resources. Many of the republican states were located in less fertile regions, such as the foothills of the Himalayas or in areas that lacked the extensive river systems that supported the larger monarchies like Magadha and Kosala.

Furthermore, the republican states did not maintain large standing armies. In many cases, military service was the responsibility of the Kshatriya clans, and while they could muster forces in times of war, they lacked the professional, full-time armies that the monarchies maintained. This made them particularly vulnerable to the more powerful and militarized monarchies, which could mobilize their forces quickly and effectively.

4.2.3 External Threats and Conquests by Monarchies

The growing strength of the monarchical states also posed a significant threat to the republics. By the 6th century BCE, monarchies such as Magadha, Kosala, Vatsa, and Avanti were expanding their territories through conquest. The republican states, with their fragmented political structures and limited military capacity, were unable to withstand these expansionist monarchies.

One of the most notable examples of this is the rise of Magadha under Bimbisara and his son Ajatashatru. Magadha’s location in the Gangetic plains provided it with fertile agricultural land and access to important trade routes, which significantly strengthened its economy and military. Bimbisara began the process of expansion through both conquest and diplomacy, and his son Ajatashatru continued these efforts, ultimately conquering the powerful Vajji confederacy.

Similarly, the Kosalan monarchy under King Prasenjit expanded its influence through military campaigns, absorbing weaker republics and incorporating their territories into its domain.

4.2.4 The Role of Diplomacy and Alliances

While military conquests were a key factor in the decline of the republics, diplomacy and marriage alliances also played a significant role in their eventual absorption by monarchies. Monarchs often used diplomatic marriages to strengthen their claims over neighboring states, including the republics.

For example, Bimbisara of Magadha is known to have forged alliances through marriage with the royal families of Kosala and Vajji, two of the most prominent republics of the time. These alliances not only helped to legitimize Magadha’s expansion but also weakened the political independence of the republics, as their ruling families became closely tied to the interests of Magadha.

4.2.5 Shift in Political Ideology: From Oligarchy to Monarchy

Over time, the republican states began to lose their appeal to the Kshatriya elite, who increasingly favored the centralized authority offered by monarchies. In a republic, power was often shared among a large number of ruling families, and decisions were made collectively in an assembly. However, this model of governance became less attractive as monarchies demonstrated the benefits of a unified leadership.

Monarchies provided a clear hierarchy and structure, which allowed for more efficient decision-making and the centralization of power. The Brahmanical tradition, which emphasized the divine right of kings, also supported the idea of monarchy over republics. This shift in political ideology, combined with the practical benefits of centralized governance, contributed to the decline of the republican states.

4.2.6 Absence of Strong Leadership

Unlike the monarchies, which were often led by charismatic and powerful rulers, the republican states did not produce strong, centralized leadership. The absence of a single ruler made it difficult for the republics to pursue long-term strategies or respond effectively to external threats. In times of war, the republican assemblies were slow to reach consensus, which hampered their ability to defend their territories.

For example, the Lichchhavis of Vajji were known for their assembly of 7707 rajas, all of whom held a share in governance. While this system promoted equality among the ruling class, it also made decision-making cumbersome. When faced with the aggressive expansionism of Magadha, the Lichchhavis were unable to organize a unified response, leading to their eventual defeat.

4.2.7 The Decline of Republican Institutions

As the monarchies continued to expand, the republican institutions of the Ganas and Sanghas began to deteriorate. The assemblies, which had once been the backbone of the republican states, became increasingly ceremonial as power shifted to a smaller group of elites. In some cases, the assembly members became puppets of the monarchs who had conquered or absorbed their states.

The assembly halls, once vibrant centers of political activity, became less important as the monarchs consolidated their power. By the time of the Mauryan Empire (322–185 BCE), many of the former republican states had been fully integrated into the monarchical system, with their assemblies either disbanded or reduced to symbolic roles.

4.2.8 Economic Decline

The economic decline of the republican states also contributed to their downfall. The monarchies, with their centralized control over agriculture and trade, were able to extract more resources from their territories and invest in infrastructure, including fortifications, roads, and irrigation systems. In contrast, the republican states lacked the centralized authority to manage large-scale economic projects, and their economies stagnated as a result.

As trade routes became increasingly important to the regional economy, the monarchies’ control over these routes allowed them to grow even wealthier, while the republican states were left behind. This economic disparity further weakened the republics, making them easy targets for conquest by the expanding monarchies.

4.2.9 Religious Influence and the Shift Toward Centralization

The religious ideologies of the time also played a role in the decline of the republics. The Brahmanical tradition, which gained prominence during the period, emphasized the importance of kingship and the divine right of rulers. This religious ideology supported the idea of centralized authority and reinforced the legitimacy of monarchies over republican forms of governance.

Additionally, the rise of Buddhism and Jainism during this period influenced the political landscape. While these religions did not directly advocate for monarchy, their teachings on non-violence and moral governance resonated with many rulers, particularly in the monarchical states. Monarchs such as Ashoka, who adopted Buddhism, used religion to legitimize their rule and promote social harmony, further diminishing the appeal of the republican states.

4.2.10 The Absorption of Republics into Larger Empires

By the time of the Mauryan Empire, many of the former republican states had been absorbed into larger empires. The Mauryan Empire, under Chandragupta Maurya and later Ashoka, expanded across much of the Indian subcontinent, incorporating both monarchies and former republican states into its centralized administration.

The Mauryan rulers maintained control through a well-organized bureaucracy, a large standing army, and a network of spies and governors. This system of governance left little room for the decentralized, republican institutions of the Ganas and Sanghas. As a result, the republican states either dissolved or were fully integrated into the imperial system, marking the end of the republican tradition in ancient India.

5. The Mahajanapadas: Overview of Key States

The Mahajanapadas were the sixteen large states that dominated the political landscape of northern India during the 6th to 4th centuries BCE. These states were spread across the Gangetic plains, north-west India, and parts of central and eastern India. They represented the culmination of a long process of tribal consolidation and territorial expansion, which began during the Vedic period.

Each Mahajanapada had its own unique political system, economy, and military structure, which shaped its interactions with neighboring states. Some, like Magadha and Kosala, were powerful monarchies, while others, like Vajji and Malla, were republican in nature. The Mahajanapadas played a crucial role in shaping the political and cultural development of ancient India, setting the stage for the rise of large empires such as the Mauryan Empire.

5.1 Magadha: The Most Powerful Mahajanapada

Among the sixteen Mahajanapadas, Magadha emerged as the most powerful and influential state. Located in the Gangetic plains in present-day Bihar, Magadha’s strategic location allowed it to control key trade routes and access to iron resources, which strengthened its economy and military.

The rise of Magadha began under the reign of Bimbisara (c. 543–491 BCE), who expanded the kingdom through both conquest and diplomatic alliances. He is credited with the annexation of Anga and the formation of alliances with Kosala and Vajji through marriage diplomacy.

Bimbisara’s son, Ajatashatru (c. 491–461 BCE), continued his father’s expansionist policies. Ajatashatru is best known for his conquest of the Vajji confederacy, a powerful republican state located in the north-east of Magadha. After a prolonged war, Ajatashatru defeated the Lichchhavis of Vajji and incorporated their territory into the Magadhan empire.

Under the later Shishunaga and Nanda dynasties, Magadha continued to expand, eventually becoming the most dominant power in north India. Its capital, Pataliputra, became one of the most important cities in ancient India, serving as the political and administrative center of the Mauryan Empire.

5.2 Kosala: The Rival of Magadha

Kosala was another powerful Mahajanapada, located to the north of Magadha, with its capital at Ayodhya. During the 6th century BCE, Kosala was ruled by King Prasenjit, a contemporary of Buddha. Under his rule, Kosala expanded its territory and frequently engaged in military conflicts with its neighbors, particularly Magadha and Vatsa.

Kosala’s rivalry with Magadha was particularly intense. Initially, the two kingdoms were allied through marriage, as Bimbisara of Magadha had married a Kosalan princess. However, after Bimbisara’s death, relations between the two kingdoms deteriorated, leading to a series of wars. Eventually, Ajatashatru of Magadha defeated Kosala and annexed its territory, further solidifying Magadha’s dominance in the region.

Kosala’s importance also extended beyond its military prowess. It was a major center of religious activity, particularly in the promotion of Buddhism. Kapilavastu, the birthplace of Gautama Buddha, was located within the kingdom of Kosala, and many of Buddha’s early disciples came from this region.

5.3 Vatsa: A Kingdom of Trade and Diplomacy

Vatsa, with its capital at Kaushambi, was one of the most prosperous Mahajanapadas. Located along the banks of the Yamuna River, Vatsa was a major center of trade and commerce, known for its cotton textiles and other goods. Its location made it a crucial link between the Gangetic plains and the Deccan plateau.

The kingdom was ruled by King Udayana, a contemporary of Buddha and a central figure in Buddhist and Jaina literature. Udayana is depicted as a powerful and ambitious ruler, known for his military campaigns and diplomatic marriages. One of the most famous legends involving Udayana is his marriage to Vasavadatta, the daughter of King Pradyota of Avanti, which helped forge an alliance between Vatsa and Avanti.

Despite its wealth and influence, Vatsa eventually fell to Magadha during the reign of Ajatashatru, who absorbed its territory into the expanding Magadhan empire.

5.4 Avanti: A Regional Power in Western India

Avanti, with its capital at Ujjain, was one of the most powerful kingdoms in western India. Avanti was divided into two regions: Northern Avanti, with its capital at Ujjain, and Southern Avanti, with its capital at Mahishmati. The kingdom was strategically located along important trade routes that connected north India with the Deccan and western India.

Under King Pradyota, Avanti was a formidable military power and frequently engaged in conflicts with Magadha, Vatsa, and other neighboring states. Pradyota is also remembered for his rivalry with Udayana of Vatsa, which was eventually resolved through marriage diplomacy when Pradyota’s daughter, Vasavadatta, married Udayana.

Despite its military strength, Avanti eventually succumbed to Magadha during the reign of Shishunaga, who defeated the last Pradyota king and incorporated Avanti into the Magadhan empire.

5.5 Vajji: The Prominent Republican Confederacy

Vajji, with its capital at Vaishali, was one of the most prominent republican states of the 6th century BCE. Unlike the monarchies of Magadha and Kosala, Vajji was a confederacy of several clans, including the Lichchhavis, Videhas, and Jnatrikas. The Vajji confederacy was known for its strong republican traditions and collective decision-making through its assembly of rajas.

However, despite its republican governance, Vajji was not immune to the pressures of the expanding monarchies. The confederacy was frequently engaged in conflicts with Magadha, and despite its strong alliances with other republican states, it eventually fell to Ajatashatru of Magadha. After a prolonged war, Vajji was absorbed into the Magadhan empire, marking the end of its independence.

5.6 Malla: The Significant Republican State

The Malla republic, located in the region corresponding to modern eastern Uttar Pradesh, played a key role in the 6th century BCE political landscape. The Mallas were a republican state like Vajji, governed by an assembly of Kshatriya clans. The political organization of the Mallas was decentralized, with power shared among the ruling elite.

The Malla territory holds significant importance in Buddhist history, as it was in Kusinara (present-day Kushinagar) that Gautama Buddha attained Mahaparinirvana (final nirvana after death). The Mallas honored Buddha by building a stupa to enshrine his relics, a symbol of their connection to Buddhism.

While the Mallas maintained their independence for a time, like other republican states, they were eventually weakened by internal divisions and external pressures from expanding monarchies such as Magadha. By the time of Ajatashatru’s expansion, the Malla republic had been significantly reduced in influence and was ultimately absorbed into the Magadhan Empire.

5.7 Kashi: The Kingdom of Religious and Commercial Importance

The kingdom of Kashi was one of the most ancient and powerful Mahajanapadas, with its capital at Varanasi (also known as Kashi or Benares). Varanasi was not only a major religious center, revered by Hindus as the holiest of cities, but also a bustling center of trade and commerce. The city’s strategic location on the banks of the Ganga River made it a hub for commercial activities and facilitated interactions with other Mahajanapadas.

Kashi was one of the early rivals of Kosala, and for centuries, these two kingdoms were engaged in a bitter struggle for dominance in northern India. Kashi was eventually absorbed into the Kosalan kingdom during the reign of King Prasenjit.

Despite its conquest by Kosala, Kashi continued to retain significant religious and cultural importance throughout ancient Indian history. It was known for its production of fine textiles, including the famous Kashya robes worn by Buddhist monks.

5.8 Kuru: The Decline of a Vedic Power

The Kuru kingdom, which was once one of the most powerful Vedic states during the Rigvedic period, had lost much of its prominence by the 6th century BCE. The Kuru kingdom, located in the region corresponding to modern-day Delhi, Haryana, and parts of western Uttar Pradesh, played a significant role in early Vedic history. It was the center of Vedic culture and rituals, and many of the Vedic texts were composed in this region.

However, by the time of the Mahajanapadas, the Kuru kingdom had become a republic, governed by a council of chiefs rather than a monarchy. The Panchala and Matsya kingdoms, located nearby, had also risen in prominence, eclipsing the once-powerful Kurus.

The Kuru republic remained relatively small compared to the larger monarchical states such as Magadha and Kosala. The political and military power of the Kuru republic gradually declined, and by the time of Alexander the Great’s invasion of India in the 4th century BCE, the Kuru state had become a minor political entity.

5.9 Panchala: The Transition to a Republic

The Panchala kingdom, located in the upper Gangetic plains between the Yamuna and Ganga rivers, was another significant power during the Mahajanapada period. Like the Kuru kingdom, Panchala was originally a monarchy but had transitioned into a republic by the 6th century BCE.

Panchala was divided into two parts: Northern Panchala, with its capital at Ahichchhatra, and Southern Panchala, with its capital at Kampilya. The Panchala people were known for their strong military tradition and their expertise in warfare.

The Panchala republic played a significant role in the political and military conflicts of the period, often allying with or opposing neighboring states such as Kosala and Kuru. Despite its republican system, the Panchala state could not match the growing power of the monarchical states like Magadha and Kosala, and by the time of the Mauryan Empire, Panchala had been absorbed into the larger political entities of the region.

5.10 Surasena: A Monarchy with Strategic Importance

The kingdom of Surasena, located in the Braj region of modern Uttar Pradesh, with its capital at Mathura, was an important monarchical state during the Mahajanapada period. Mathura, situated on the banks of the Yamuna River, was not only a significant trade center but also an important religious center associated with the worship of Lord Krishna.

Avantiputra, the king of Surasena, was a contemporary of Gautama Buddha and a disciple of his teachings. The kingdom played a crucial role in the spread of Buddhism, and Mathura became a major center for Buddhist art and learning in the centuries that followed.

Surasena’s strategic location on the Yamuna River and its proximity to Mathura, a major urban center, gave it considerable influence over the northern trade routes. However, Surasena’s political power was not as strong as some of the larger Mahajanapadas like Magadha or Kosala, and it was eventually absorbed into Magadha during the later Mauryan expansion.

5.11 Vajji: A Powerful Republican Confederacy

The Vajji confederacy, with its capital at Vaishali, was one of the most prominent republican states in ancient India. Unlike many other Mahajanapadas, Vajji was governed by a collective of Kshatriya clans, including the Lichchhavis, Videhas, and Jnatrikas. The confederacy operated on the principles of republican governance, with decisions made collectively by a council of rajas.

Vaishali, the capital of the Vajji confederacy, was a prosperous city and an important center for both Buddhism and Jainism. Mahavira, the 24th Tirthankara of Jainism, was born in Vaishali, and Gautama Buddha visited the city frequently. Vaishali was known for its advanced political institutions, and the Vajjis were proud of their republican traditions.

However, the Vajji confederacy could not withstand the expansionist ambitions of Magadha. Under Ajatashatru, Magadha waged a prolonged war against the Vajjis, eventually conquering the confederacy and incorporating its territory into the Magadhan Empire. The fall of the Vajji confederacy marked the end of republican rule in the region and the beginning of centralized monarchical control under Magadha.

5.12 Kamboja: A Frontier State

The Kamboja kingdom, located in the north-western part of the Indian subcontinent, corresponded to the Hazara district of modern Pakistan and parts of Kashmir. The Kambojas were known for their expertise in horse breeding and military prowess. They were a martial people, frequently involved in conflicts with both Indian and foreign powers.

Kamboja’s geographical location on the north-western frontier made it a strategically important state. It served as a gateway for invasions from Central Asia and Persia and was often caught between the competing powers of Persia and the Indian Mahajanapadas.

The Kambojas are mentioned in both Indian and Greek texts, particularly during the period of Alexander the Great’s invasion of India. The Kambojas were known for their republican system of governance, similar to the other republican states of the time, though they were eventually absorbed into the expanding empires of Magadha and later Maurya.

5.13 Assaka: The Southernmost Mahajanapada

Assaka was the southernmost of the sixteen Mahajanapadas and was located along the banks of the Godavari River in modern Maharashtra. Its capital, Potana (also known as Potali or Podana), was a key city in the southern region. Assaka was known for its military power and its ability to maintain its independence despite its proximity to larger northern kingdoms.

Assaka played a crucial role in the expansion of Vedic culture into southern India. The kingdom’s strategic location allowed it to control the southern trade routes and to engage in commerce with both northern India and South India.

Assaka was unique among the Mahajanapadas in that it was the only major state located south of the Vindhya mountains, marking the beginning of the expansion of Aryan culture into the southern regions of the subcontinent. Despite its geographic isolation from the northern states, Assaka maintained strong trade and cultural links with the Gangetic plains.

5.14 Matsya: A Lesser-Known Mahajanapada

The Matsya kingdom, located in the Jaipur-Alwar region of Rajasthan, was one of the smaller Mahajanapadas. Its capital was Viratanagara (modern Bairat), and it played a secondary role in the political landscape of the time.

Matsya was primarily known for its cattle rearing and pastoral economy. The kingdom’s location on the fringes of the Gangetic plains meant that it was often caught between the larger and more powerful states, such as Panchala and Kuru.

Despite its relatively small size, Matsya was involved in the military conflicts of the region and had ties to the more prominent Mahajanapadas. It was eventually absorbed into the larger kingdoms during the period of the Mauryan Empire.

6. The Decline and Absorption of the Mahajanapadas

By the 4th century BCE, the political landscape of northern India had undergone significant changes. The monarchical states, particularly Magadha, had emerged as the dominant powers, while the republican states were either weakened by internal strife or absorbed by expanding monarchies.

The decline of the Mahajanapadas was largely a result of the growing power of the monarchical states and their ability to centralize authority and mobilize resources more effectively than the republics. The monarchies of Magadha, Kosala, Vatsa, and Avanti had developed large standing armies, improved agricultural production, and established strong administrative systems, which allowed them to expand their territories through conquest and diplomacy.

6.1 The Rise of Magadha as the Dominant Power

The ultimate victor in this process of state formation and consolidation was Magadha, which, under the leadership of kings such as Bimbisara, Ajatashatru, and the later Mauryan rulers, established a vast empire that encompassed much of northern India.

Magadha’s strategic location, access to iron resources, and control over important trade routes gave it a decisive advantage over its rivals. The conquest of neighboring states, including Kosala, Vajji, and Avanti, solidified Magadha’s dominance and laid the foundation for the rise of the Mauryan Empire under Chandragupta Maurya.

By the time of Alexander the Great’s invasion of India in 326 BCE, Magadha was the most powerful state in the region, with Pataliputra as its capital. The Mauryan Empire, which emerged from the Magadhan state, would go on to become the first pan-Indian empire, uniting most of the Indian subcontinent under a single ruler.

6.2 The Role of Geography and Resources in the Rise of Magadha and Decline of other Mahajanapadas

One of the significant factors that contributed to the decline of many Mahajanapadas was the geographical advantage enjoyed by certain states, especially Magadha. Located in the fertile Gangetic plains, Magadha had access to rich agricultural resources, ensuring a stable and abundant food supply. The Ganga and its tributaries also provided essential trade routes that connected Magadha to other regions, allowing for the easy movement of goods and people.

In contrast, other Mahajanapadas such as Kuru and Matsya did not enjoy the same level of agricultural productivity, nor did they control key trade routes. Their geographic location often limited their ability to expand or sustain large populations. As a result, they were more vulnerable to conquest by better-resourced and strategically located states like Magadha.

Furthermore, Magadha’s proximity to the mineral-rich hills of present-day Bihar and Jharkhand provided it with ample access to iron and other metals. This resource allowed Magadha to equip its armies with superior iron weapons, giving it a significant advantage over other states that relied on older technologies. The use of iron tools also revolutionized agriculture in Magadha, enabling more efficient cultivation and an increase in agricultural output, further strengthening the state’s economy and military.

6.3 The Integration of the Mahajanapadas into the Mauryan Empire

The rise of the Mauryan Empire under Chandragupta Maurya marked the final phase of the consolidation of the Mahajanapadas into a unified Indian state. Chandragupta, with the guidance of his advisor Chanakya (Kautilya), used a combination of diplomacy, warfare, and alliances to conquer the remaining independent Mahajanapadas and integrate them into the growing Mauryan Empire.

Chandragupta’s rise to power was marked by his defeat of the Nanda dynasty, which had ruled Magadha before him. This victory gave Chandragupta control over the vast resources and territories of Magadha, including its capital, Pataliputra. From there, he launched a series of military campaigns to subdue the other Mahajanapadas, including Kosala, Vatsa, and Avanti.

The Mauryan administrative system was highly centralized and efficient, with a bureaucracy that extended across the empire. The integration of the Mahajanapadas into this system marked the end of their independence as individual states. Under the Mauryan rule, the territories of the former Mahajanapadas were divided into provinces, each governed by a Mauryan official who was directly accountable to the central authority in Pataliputra.

This administrative centralization allowed the Mauryan rulers to maintain tight control over the vast empire, ensuring that resources and wealth flowed from the provinces to the imperial treasury. The Arthashastra, written by Kautilya, provides detailed insights into the Mauryan state’s governance, including its taxation policies, military strategies, and legal systems, all of which contributed to the stability and expansion of the empire.

6.4 The Influence of Religion on the Mahajanapadas and Their Integration

The religious landscape of ancient India during the Mahajanapada period was dynamic and evolving. The rise of Buddhism and Jainism in the 6th century BCE coincided with the political rise of many Mahajanapadas, particularly Magadha, where these new religious movements found strong support.

The spread of Buddhism was particularly significant in the context of the Mahajanapadas. Gautama Buddha, born in Lumbini, near Kapilavastu, which was part of the Shakya republic, traveled extensively across the Mahajanapadas, preaching his message of non-violence and compassion. The rulers of several Mahajanapadas, including Bimbisara of Magadha and Prasenjit of Kosala, became early patrons of Buddhism, providing support for the construction of monasteries and the spread of Buddhist teachings.

After the integration of the Mahajanapadas into the Mauryan Empire, Ashoka, the third Mauryan emperor, became a devout follower of Buddhism. His conversion after the Kalinga war led to the promotion of Buddhism across his empire, including the former Mahajanapadas. Ashoka’s famous edicts, inscribed on pillars and rocks throughout the empire, propagated Buddhist values and marked the moral transformation of the Mauryan state.

Jainism also had a significant influence in the Mahajanapadas. Mahavira, the 24th Tirthankara of Jainism, was born in Vaishali, the capital of the Vajji confederacy, and like Buddha, he traveled extensively, spreading his teachings. Many republican states, including Vajji and Malla, were early supporters of Jainism. The integration of these republican states into the Mauryan Empire did not diminish their religious traditions. In fact, both Buddhism and Jainism continued to flourish under the Mauryas, especially during Ashoka’s reign.

6.5 The Transition from Regional Powers to a Pan-Indian Empire

The consolidation of the Mahajanapadas into the Mauryan Empire represents one of the most significant transitions in ancient Indian history. The regional kingdoms and republics that had once dominated the political landscape were now part of a centralized imperial system, with a single ruler governing vast territories from Pataliputra.

This transition was not without its challenges. The integration of diverse regions with different political systems, languages, cultures, and economies required a highly effective administrative system. The Mauryan bureaucracy, with its network of governors, tax collectors, and military commanders, played a crucial role in maintaining order across the empire.

One of the key strategies employed by the Mauryan rulers to integrate the Mahajanapadas was the promotion of a common cultural and legal framework. The Mauryan legal system, as outlined in the Arthashastra, was applied uniformly across the empire, helping to standardize governance and reduce regional differences. At the same time, the promotion of Buddhism under Ashoka provided a common religious and moral framework that helped to unify the empire.

However, despite the success of the Mauryan Empire in integrating the Mahajanapadas, the process was not without resistance. In some regions, particularly in the former republican states, there were tensions between the traditional oligarchic governance systems and the centralized Mauryan administration. These tensions would resurface in later periods, particularly after the decline of the Mauryan Empire, when many of these regions regained a degree of independence.

6.6 The Legacy of the Mahajanapadas in Indian History

The Mahajanapadas played a crucial role in shaping the political, cultural, and religious landscape of ancient India. Even after their absorption into larger empires like the Mauryan Empire, their legacy continued to influence Indian society for centuries.

The republican traditions of states like Vajji, Malla, and Shakya left a lasting impact on the political thought of the time. Although the republican system of governance declined during the Mauryan period, the idea of collective decision-making and councils continued to influence Indian politics, particularly in the form of village councils and local governance.

The rise of urban centers during the Mahajanapada period also had a lasting impact on India’s economic and cultural development. Cities like Pataliputra, Varanasi, and Ujjain became major centers of trade, learning, and religious activity. These cities continued to play important roles in Indian history long after the decline of the Mahajanapadas, serving as hubs of commerce and culture during the Gupta Empire and later periods.

Moreover, the spread of Buddhism and Jainism during the Mahajanapada period had a profound impact on Indian religious and cultural life. The patronage of these religions by the rulers of the Mahajanapadas, particularly in Magadha, helped to establish Buddhism and Jainism as major religious traditions in India. These religions spread across the Indian subcontinent and beyond, influencing the development of cultures in Southeast Asia, Central Asia, and East Asia.

7. The Political Structures of the Mahajanapadas

The political structures of the Mahajanapadas were diverse, encompassing both monarchical and republican systems. These political arrangements evolved in response to the changing socio-economic conditions of the period and played a significant role in shaping the dynamics of power across ancient India.

7.1 Monarchical Mahajanapadas

Monarchical states were the dominant political structure among the Mahajanapadas. In these states, power was centralized in the hands of a single ruler, the king, who was often seen as divinely ordained or as the ultimate authority in matters of governance, justice, and religion. Monarchical states included Magadha, Kosala, Kashi, Vatsa, Avanti, and Surasena.

The king in monarchical states enjoyed absolute power, and his authority was often legitimized through religious rituals and ceremonies. For example, the Rajasuya and Ashvamedha sacrifices were significant rituals that not only established the divine right of the king to rule but also served as a public display of his military and political dominance.

In these monarchical states, the king was assisted by a council of ministers or advisors, known as the sabha or parishad, which helped in the administration of the state. However, the king’s power often superseded that of the council, and he had the final say in all matters. The administration was further divided into various departments responsible for the collection of taxes, maintenance of law and order, and management of the military.

The monarchical Mahajanapadas were characterized by the formation of standing armies, which played a critical role in the expansion of the state’s territory. These armies were often led by hereditary generals and were equipped with iron weapons, a technology that gave many of these states a military advantage over their rivals. Agricultural surpluses and control over trade routes also provided these states with the wealth necessary to maintain their armies and fund state projects.

7.2 Republican Mahajanapadas

In contrast to the monarchical Mahajanapadas, several states were governed by republican forms of government. These republican states, also known as gana-sanghas, included Vajji, Malla, Shakya, and Kamboja. In these states, power was not concentrated in the hands of a single ruler but was instead distributed among a group of nobles or elders, typically from the Kshatriya class, who made decisions collectively in an assembly.

The ruling elite in these republican states were often referred to as rajas, but unlike in monarchical systems, these rajas were not kings but members of a governing council. The assembly, also known as the santhagara or gana-parishad, was the highest decision-making body in the republic. Members of the ruling families or clans gathered to discuss and decide on matters of state, including military campaigns, diplomacy, and legal disputes.

The republican system allowed for a greater degree of collective decision-making than the monarchical system. However, it was not a democracy in the modern sense. Power remained concentrated in the hands of a small number of aristocratic families, and the common people had little say in the governance of the state.

Despite this, the republican states demonstrated a remarkable level of political organization and resilience, often managing to resist the expansionist ambitions of their monarchical neighbors for extended periods. The Vajji confederacy, for example, was one of the most powerful republican states and successfully maintained its independence for many years before being absorbed into the Magadhan Empire under Ajatashatru.

7.3 Differences Between Monarchies and Republics

While both monarchical and republican Mahajanapadas were powerful political entities, there were significant differences in their governance and social structures. In monarchies, power was highly centralized, with the king at the top of the hierarchy, supported by a bureaucracy that helped administer the state. The king was often seen as a divinely chosen leader, and his authority was absolute.

In republican states, governance was more decentralized, with power distributed among the members of the ruling elite. Decisions were made collectively, and the office of the leader, often called the ganapati or sanghamukhya, was typically an elected position. This collective governance structure allowed for greater input from different clans or families, although the actual decision-making power remained confined to the aristocratic class.

Economically, the monarchies tended to be more centralized, with the king collecting taxes from peasants and overseeing large-scale agricultural and commercial activities. The republican states, on the other hand, were often smaller and less centralized, with each ruling family maintaining control over its own lands and resources.

In terms of military organization, the monarchical states generally had larger, more professional standing armies, while the republican states relied more on militias formed from the citizenry. This difference in military organization often put the republics at a disadvantage in prolonged conflicts with the more militarized monarchies.

7.4 The Decline of the Republican States

By the 4th century BCE, the republican states began to decline as the more centralized and militarily powerful monarchical states, particularly Magadha, expanded their territories. The republican states were often smaller and less capable of sustaining large, standing armies, making them vulnerable to conquest by their monarchical neighbors.

One of the key reasons for the decline of the republican states was internal divisions within the ruling councils. The collective decision-making process, while offering a form of shared governance, often led to factionalism and disunity among the ruling elites. This lack of unity made it difficult for the republican states to respond effectively to external threats.

Additionally, the monarchical states had access to greater economic resources, which allowed them to fund large armies, build infrastructure, and consolidate power. The republican states, with their more fragmented governance structures and smaller economic bases, were unable to compete with the growing might of the monarchies, particularly Magadha, which, under leaders like Bimbisara and Ajatashatru, systematically absorbed many of the republican states into its expanding empire.

8. The Military Organization of the Mahajanapadas

The military systems of the Mahajanapadas were crucial in shaping their political fortunes. While both monarchies and republics maintained armies, the scale, organization, and strategies employed by each varied significantly, influencing the outcomes of territorial conflicts and their ability to withstand external threats.

8.1 Monarchical Military Strength

Monarchical Mahajanapadas such as Magadha, Kosala, and Avanti boasted large, organized armies that were supported by a strong central administration. These armies were divided into different units, including infantry, cavalry, chariots, and war elephants. The use of iron weapons, which became widespread in the 6th century BCE, gave these armies a significant technological advantage.

The military strategies of these states were often focused on expansion. Kings like Ajatashatru of Magadha used their armies to systematically conquer neighboring territories, integrating them into a centralized state. The fortification of cities and the development of siege warfare allowed monarchical states to effectively capture well-defended cities and strongholds, further expanding their influence.

8.2 Republican Military Organization

Republican states, on the other hand, relied more on citizen militias than professional standing armies. These militias were composed of the ruling Kshatriya families and their dependents, who were called upon to defend the state in times of conflict. While these militias were capable of defending against smaller raids or invasions, they were often outmatched by the larger, professional armies of the monarchical states.

In some cases, republican states like the Vajji confederacy were able to resist invasion through the collective efforts of their ruling families, but the lack of a centralized command structure often limited their military effectiveness in prolonged conflicts.

9. Economic Foundations of the Mahajanapadas

The economic systems of the Mahajanapadas were closely tied to their political power and military strength. The wealth of these states was largely derived from agriculture, trade, and craft production, and the ability to control and tax these economic activities was essential for maintaining state power.

9.1 Agricultural Economy

Agriculture was the primary economic activity in the Mahajanapadas, and the fertility of the Gangetic plains played a key role in the rise of powerful states like Magadha and Kosala. The introduction of iron plows and other agricultural tools significantly increased crop yields, leading to the growth of surplus production. This surplus allowed the ruling elites to extract taxes from the peasantry and fund their armies, bureaucracies, and public works.

9.2 Trade and Commerce

Trade was another vital component of the Mahajanapada economies, with states like Kashi, Kosala, and Magadha controlling important trade routes that connected the Gangetic plains to other regions of India and beyond. The use of punch-marked coins, which first appeared in this period, facilitated trade and helped standardize economic transactions across the different states.

9.3 Urbanization and the Growth of Cities

The period of the Mahajanapadas witnessed significant urbanization, with the rise of large cities that became centers of commerce, craft production, and political power. Cities like Pataliputra, Rajagriha, Varanasi, Vaishali, and Ujjain were major urban centers during this time, serving as hubs for trade and administrative control.

The cities were not only political capitals but also bustling marketplaces where goods from across the subcontinent and beyond were traded. Texts from this period mention merchants traveling far and wide, exchanging luxury goods such as textiles, spices, and precious stones. Cities were also centers of crafts, with specialized production of goods such as pottery, metalwork, and textiles, which were often traded for agricultural products from rural areas.

Urbanization was closely tied to the political power of the Mahajanapadas. The ability to control and tax urban markets gave the ruling classes the wealth they needed to maintain large armies and sophisticated administrative structures. Additionally, cities served as cultural centers where intellectuals, religious leaders, and artists could gather, contributing to the flourishing of philosophical and religious thought during this period.

9.4 Taxation and State Revenue

Taxation was a key element in the economic systems of the Mahajanapadas. The revenue collected from taxes funded the administrative and military machinery of these states. Taxes were typically levied on agricultural produce, trade, and sometimes on the artisans and craftsmen who produced goods for the markets.

In monarchical states, the king was responsible for collecting taxes, with the help of a bureaucratic apparatus. Land taxes were common, with the state typically claiming a portion of the produce from farmers. In some cases, this could be as much as one-sixth of the total harvest. In republican states, taxation was less centralized, but the ruling elite still imposed taxes on the population to fund collective defense and public works.

Revenue from trade was also crucial, particularly in states like Kashi and Kosala, which controlled important trade routes. Taxes were imposed on goods passing through key commercial hubs and on merchants operating within the cities. The control of river trade routes along the Ganga and its tributaries gave some states a significant advantage, allowing them to collect tolls from boats and merchants traveling along these waterways.

9.5 Role of Iron in Economic Growth

The introduction of iron technology played a transformative role in the economy of the Mahajanapadas. Iron plows and tools revolutionized agriculture, allowing farmers to cultivate more land and produce higher yields. The expansion of agriculture in the Gangetic plains provided the surplus food necessary to support larger populations and urban centers.

Iron also played a critical role in military technology, giving the Mahajanapadas the ability to forge stronger weapons such as swords, spears, and arrowheads. The availability of iron resources in states like Magadha provided a significant economic and military advantage, allowing these states to dominate their rivals.

The spread of iron technology across northern India helped to drive the economic expansion that underpinned the rise of powerful states. The increased agricultural productivity and trade facilitated by iron tools contributed to the wealth of the Mahajanapadas, enabling them to build cities, raise armies, and engage in large-scale public works projects.

10. Religious and Cultural Developments in the Mahajanapada Period

The Mahajanapada period was not only a time of political and economic transformation but also a period of significant religious and cultural development. It was during this time that new religious movements, particularly Buddhism and Jainism, emerged, challenging the established Vedic traditions and offering new philosophical and ethical frameworks.

10.1 The Rise of Buddhism and Jainism

Both Buddhism and Jainism arose during the 6th century BCE in response to the social, political, and religious conditions of the time. These new religions rejected the ritualistic aspects of Brahmanism and the dominance of the Brahmin caste, advocating instead for personal spiritual development, non-violence, and compassion.

Gautama Buddha, born as Siddhartha Gautama in the Shakya republic (one of the Mahajanapadas), founded Buddhism, which emphasized the path to enlightenment through the Four Noble Truths and the Eightfold Path. Buddhism spread rapidly across the Mahajanapadas, particularly in states like Magadha, where rulers like Bimbisara and Ajatashatru became patrons of the new faith.

Similarly, Mahavira, the 24th Tirthankara of Jainism, was born in Vaishali, the capital of the Vajji confederacy. Jainism, like Buddhism, emphasized the rejection of materialism, non-violence (ahimsa), and the pursuit of spiritual purity. Jainism found support among the merchant classes in cities like Vaishali, Kashi, and Kosala, where its teachings resonated with the economic and social realities of urban life.

10.2 The Impact of Buddhism and Jainism on the Mahajanapadas

The spread of Buddhism and Jainism had profound impacts on the cultural and political landscape of the Mahajanapadas. Both religions rejected the rigid social hierarchy of the varna system, offering an alternative ethical framework that appealed to many, especially the lower classes and merchants.

Rulers like Bimbisara and Ajatashatru of Magadha supported these new religious movements, providing land and resources for the construction of monasteries and temples. These rulers recognized the political value of aligning themselves with Buddhism and Jainism, which promoted social harmony and stability.

The construction of stupas, viharas, and other religious monuments during this period reflected the growing influence of these new faiths. Pataliputra, the capital of Magadha, became a major center for Buddhist learning and culture, attracting scholars and monks from across the subcontinent.

10.3 The Role of Brahmanism and the Vedic Tradition

Despite the rise of Buddhism and Jainism, Brahmanism and the Vedic tradition continued to play a central role in the religious and cultural life of the Mahajanapadas. The Brahmin class remained influential, particularly in the monarchical states, where kings relied on Brahmins to perform sacrifices and rituals that legitimized their rule.

The Upanishads, a series of philosophical texts that emerged during this period, represented a shift within the Vedic tradition towards more abstract and introspective forms of spiritual thought. The Upanishads emphasized the concepts of Brahman (the ultimate reality) and Atman (the individual soul), offering a philosophical framework that would continue to influence Indian thought for centuries.

While Buddhism and Jainism challenged the dominance of Brahmanism, the Vedic tradition adapted to these challenges by evolving its own philosophical and ethical teachings. The competition between these religious traditions contributed to the rich intellectual and spiritual life of the Mahajanapadas, laying the groundwork for future developments in Indian philosophy and religion.

11. Conclusion: The Mahajanapadas and the Foundations of Indian Civilization

The Mahajanapada period was a time of great political, economic, and cultural transformation in ancient India. The rise of large territorial states marked the shift from the earlier Vedic tribal systems to more complex forms of governance. These states, both monarchical and republican, laid the foundations for the development of urban centers, trade networks, and religious movements that would shape Indian civilization for centuries to come.

The eventual decline of the Mahajanapadas and their absorption into larger empires like the Mauryan Empire represented the beginning of a new era in Indian history, one characterized by imperial rule and the unification of vast territories under a centralized authority. However, the legacy of the Mahajanapadas, particularly their contributions to political thought, urbanization, and religion, continued to influence Indian society long after their decline.

As we reflect on the history of the Mahajanapadas, it becomes clear that this period was not merely a precursor to the Mauryan Empire but a critical phase in the development of Indian civilization. The innovations in governance, religion, and economy that emerged during this time laid the groundwork for the rise of empires, the spread of religious ideas, and the flourishing of Indian culture in the centuries that followed.

MCQs

- Which of the following Mahajanapadas was a republic and not a monarchy?

- (A) Magadha

- (B) Kosala

- (C) Vajji

- (D) Kashi

- Consider the following statements regarding the Mahajanapada period:

- All Mahajanapadas followed a monarchical system of governance.

- The introduction of iron tools in agriculture led to surplus production and urbanization.

- The Vajji Mahajanapada was located in modern-day Bihar.

- (A) 1 only

- (B) 2 and 3 only

- (C) 2 only

- (D) 1 and 3 only

- Which of the following Buddhist texts provides a detailed list of the sixteen Mahajanapadas?

- (A) Sutta Pitaka

- (B) Anguttara Nikaya

- (C) Vinaya Pitaka

- (D) Digha Nikaya

- Which of the following Mahajanapadas was the earliest to establish its dominance by absorbing others during the 6th century BCE?

- (A) Avanti

- (B) Magadha

- (C) Kosala

- (D) Vatsa

- Which among the following was the capital of the Avanti Mahajanapada during the later Vedic period?

- (A) Ujjayini

- (B) Varanasi

- (C) Pataliputra

- (D) Rajagriha

Mains Questions

- Examine the socio-political and economic factors that led to the rise of the Mahajanapadas in 6th century BCE India. How did their governance structures differ from the earlier Vedic period?

- Discuss the role of iron technology in the expansion of agriculture and urbanization during the Mahajanapada period. How did this technological advancement contribute to the rise of powerful states like Magadha?

- Analyze the significance of republics (gana-sanghas) such as Vajji and Malla during the Mahajanapada period. How did their political structures and ideologies differ from the monarchical states?

- Evaluate the role of Buddhism and Jainism in shaping the political and social landscape of the Mahajanapada states. To what extent did these religious movements challenge the existing Vedic order?

- Discuss the causes behind the decline of republican Mahajanapadas and the rise of monarchical states, particularly Magadha, during the late 6th century BCE. How did this transition impact the socio-political dynamics of northern India?

[…] Formation of States (Mahajanapadas): Republics and Monarchies […]

[…] Formation of States (Mahajanapadas): Republics and Monarchies […]

[…] Formation of States (Mahajanapadas): Republics and Monarchies […]

[…] Formation of States (Mahajanapadas): Republics and Monarchies […]

[…] Formation of States (Mahajanapadas): Republics and Monarchies […]

[…] Formation of States (Mahajanapadas): Republics and Monarchies […]

[…] Formation of States (Mahajanapadas): Republics and Monarchies […]

[…] Formation of States (Mahajanapadas): Republics and Monarchies […]