January 25, 2026 4:29 am

Original Home and Identity of the Aryans

- The term “Arya” is primarily cultural, meaning kinsman or companion, and is mentioned in the Rig Veda.

- Theories on the original homeland of the Aryans remain varied, with some suggesting Europe, while others favor Central Asia or regions closer to India.

- Early scholars like Penka proposed Germany as the homeland, but this racial classification approach has been abandoned in favor of linguistic connections.

Linguistic Group and Homeland Debate

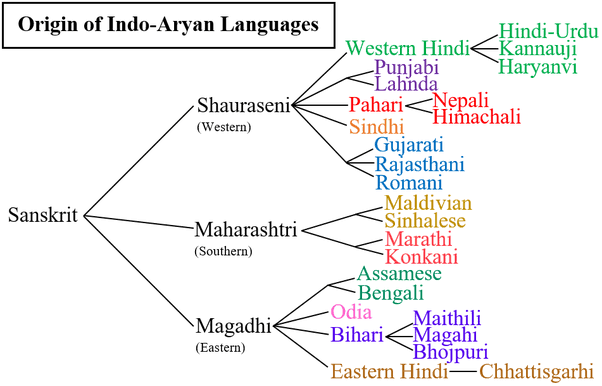

- The Indo-Aryans are now identified as part of a broader Indo-European linguistic group.

- There is significant linguistic affinity between Sanskrit and other Indo-European languages like Greek, Latin, and Persian, with shared words like “matri” and “pitri” paralleling “mater” and “pater” in Latin.

- The Vedas reflect ties with Iran, and early Aryans likely traversed through Iran before arriving in India, as seen in shared elements between the Rig Veda and the Iranian Avesta.

- There are references to Aryan names in ancient inscriptions from Iraq, Anatolia, and Mesopotamia, indicating a widespread Indo-European presence.

Aryan Migration: Myth vs. Reality

- Linguistic and archaeological evidence points to the arrival of Aryans in India around 1500 BCE, but large-scale invasion theories have been debunked.

- Some archaeological artifacts, such as socketed axes and Painted Grey Ware pottery, have been connected to the Aryan presence in northwestern India, but there’s little evidence supporting an Aryan invasion as the cause of Harappan decline.

- More historians now support a theory of Aryan migration in waves, rather than a violent invasion.

Early Aryan Settlement in India

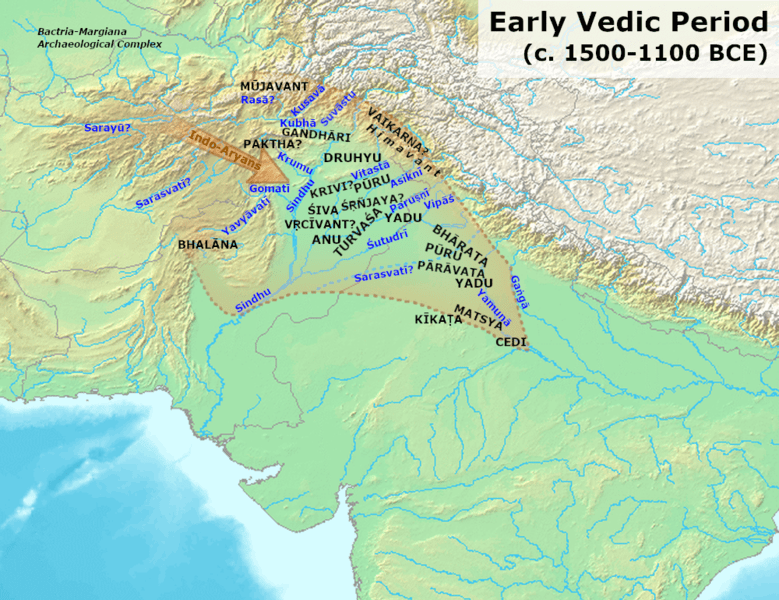

- The Aryans initially settled in regions like eastern Afghanistan, Punjab, and western Uttar Pradesh, particularly around the rivers mentioned in the Rig Veda (e.g., Sindhu, Sarasvati, and Yamuna).

- This region, known as the land of the seven rivers, became the cradle of early Aryan culture.

Tribal Conflicts and Expansion

- Aryans engaged in conflicts both with indigenous populations (such as the Panis, Dasas, and Dasyus) and among themselves.

- Notably, the Battle of Ten Kings (Dasarajna) saw tribal wars that shaped the political landscape of early Aryan society, with the victorious Bharata tribe eventually forming alliances with other groups like the Purus, giving rise to the powerful Kuru dynasty.

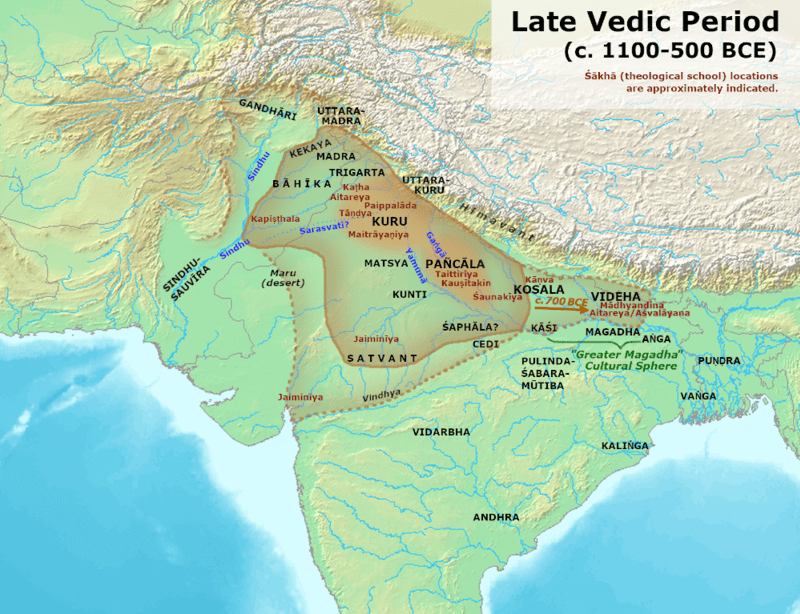

- The Aryans gradually expanded eastward into regions like Kosala (Eastern U.P.) and Videha (North Bihar), establishing themselves further in India during the Later Vedic Period.

Later Vedic Period Expansion (1000-500 BCE)

- Aryans moved into eastern U.P. and north Bihar, with archaeological evidence (such as Painted Grey Ware) supporting this expansion.

- The Kuru-Panchala alliance was dominant in the upper Ganga-Yamuna Doab region, with Hastinapur as their capital, associated with the epic Mahabharata.

- Iron technology played a crucial role in land clearance and expansion into new territories.

- The Aryans also began moving southwards, although the exact timeline is unclear. By the end of the Vedic age, Aryan kingdoms had extended to regions in Vidarbha, Nasik, and along the Godavari River.

Religious and Philosophical Literature

The Vedic Texts

- Definition of Veda: The term veda originates from the root word vid, meaning ‘to know’. Hence, Veda refers to the sacred knowledge contained within the Vedic texts.

- Historical Significance: These texts form the oldest layer of Sanskrit literature and are considered the most ancient scriptures in Hinduism.

- Sruti vs. Smriti: Vedic texts are referred to as sruti (“what is heard”) in contrast to smriti (“what is remembered”), distinguishing them from other religious texts.

- Apauruseya: Hindus believe that the Vedas are apauruseya (authorless), and are seen as divine revelations received by ancient sages through deep meditation.

- Creation of Vedas: In the Mahabharata, the creation of the Vedas is attributed to Brahma, while the hymns themselves suggest they were crafted by Rishis (sages) through inspired creativity.

Types of Vedas

| Veda | Description |

|---|---|

| Rigveda | A compilation of 1,028 hymns divided into 10 mandalas, portraying early Vedic life in India. |

| Samaveda | Verses borrowed mainly from the Rigveda but arranged in a musical form for singing. |

| Yajurveda | Contains hymns and rituals, reflecting the socio-political context, for both public and private recitation. |

| Atharvaveda | A collection of magical spells and charms aimed at protecting against evil spirits and diseases. |

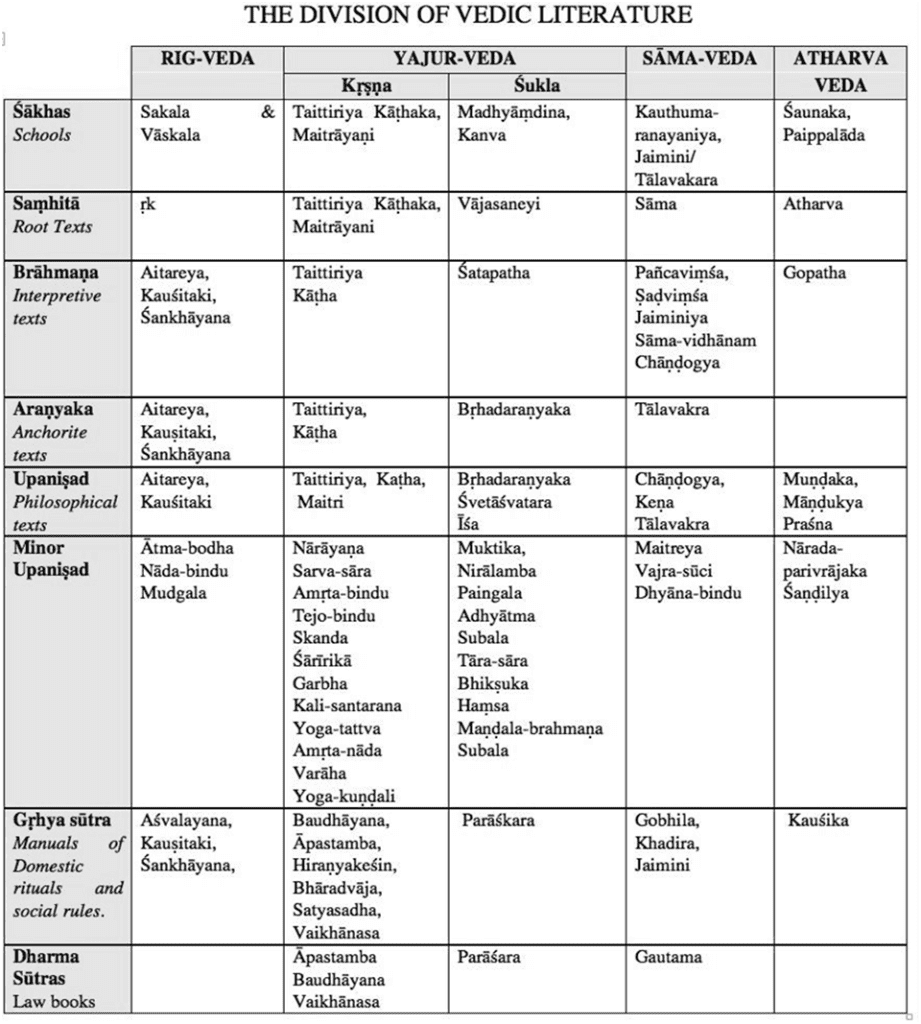

Subdivisions of Vedic Literature

| Text Type | Description |

|---|---|

| Samhitas | Collections of hymns or mantras. |

| Brahmanas | Ritualistic formulae explaining the social and religious significance of rituals. |

| Aranyakas | Texts focusing on rituals, sacrifices, and symbolic ceremonies. |

| Upanishads | Philosophical texts discussing meditation, spirituality, and the nature of existence (Brahman and Atman). |

- Upanishads: These form the concluding part of the Vedic texts and are also known as Vedanta, which translates to “the end of the Vedas”. They focus on concepts like Brahman (Ultimate Reality) and Atman (the Self), laying the foundation for Hindu philosophical traditions.

- Aranyakas and Upanishads: Aranyakas are regarded as karma-kanda (ritualistic sections), whereas the Upanishads are known as jnana-kanda (knowledge and spirituality sections).

The Philosophy of the Upanishads

- The Upanishads present profound philosophical inquiries into the ultimate truth behind creation. Many Indian philosophical systems, including those of Samkara and Ramanuja, are grounded in the Upanishads (Vedanta).

- Brahman and Atman: Central to the Upanishads is the notion of Brahman (the ultimate cosmic principle) and Atman (the individual self). The unity between these two is summarized in the famous phrase Tat Tvam Asi (“Thou art That”), symbolizing the identity of individual consciousness with the universal spirit.

- World-Soul and Individual Self: The concept of Atman evolved from earlier notions of Prajapati (the personal creator) to Brahman, the impersonal source of all creation. This philosophical transition epitomizes India’s religious and intellectual progress.

Key Doctrines

- Doctrine of Rebirth: The Upanishads introduced the idea of transmigration of the soul, where the soul transitions from one body to another across lifetimes.

- Doctrine of Karma: This doctrine explains that one’s actions determine their fate in future lives, thus offering an explanation for suffering and social inequality. The emphasis is on conduct rather than birth or status.

- Salvation through Knowledge: The Upanishads emphasize knowledge (jnana) as the path to liberation, rather than salvation through rituals or faith. The realization of the unity between Brahman and Atman leads to ultimate liberation.

Sruti Literature as a Source of History

- Sruti: Literally meaning “that which is heard”, the Vedas are considered sruti literature. Various interpretations of Indo-Aryan history have been drawn from these texts, with nationalist historians idealizing the Vedic age and later historians offering more balanced interpretations.

- Challenges in Extracting History: Given the vast, complex, and ancient nature of the Vedas, extracting historical facts is difficult. Variations in word meanings and the lack of original texts make interpretation challenging. The oral tradition further complicates the issue, as the oldest surviving manuscripts are from the 11th century CE.

Geographical Context in the Vedic Texts

- Sapta Saindhavas: Early Aryans referred to the region they settled in as Sapta Saindhavas (the land of seven rivers).

- Aryavarta: Over time, Aryan settlement expanded to include most of northern India, referred to as Aryavarta.

Rivers in the Vedic Texts

| River | Modern Name/Location |

|---|---|

| Sindhu | Indus |

| Saraswati | Ghaggar-Hakra (Haryana and Rajasthan) |

| Shutudri | Sutlej |

| Vipas | Beas |

| Parushni | Ravi |

| Asikni | Chenab |

| Vitasta | Jhelum |

| Gomati | Gomal |

| Krumu | Kurram |

| Kubha | Kabul |

| Suvastu | Swat (Northern Afghanistan) |

Mountains and Seas

- Mountains: The Rig Vedic Aryans were aware of the Himalayas and other ridges like Mujavant and Suleman but had little knowledge of regions south of the Yamuna.

- Seas: References to the sea in the early Rig Veda are ambiguous, as the word samudra likely refers to large bodies of water. However, later Vedic texts mention the seas, indicating the Aryans’ growing awareness of the Bay of Bengal and Arabian Sea.

Vedic Period: Political, Social, and Economic Life

Transformation from Rig Vedic Period to Later Vedic Period

The Vedic period, which spanned from 1500 to 500 B.C., is divided into the Early Vedic or Rig Vedic period (1500-1000 B.C.) and the Later Vedic period (1000-500 B.C.). This period witnessed significant changes in political, social, and economic life as well as religious practices, leading to the establishment of monarchies and the emergence of the varna system.

Political Life

Early Vedic Period (1500–1000 B.C.)

Administrative Divisions

- Kula: The basic unit of political organization was the family (kula).

- Grama: Several families formed a village (grama), led by a gramani.

- Visu: A group of villages formed a district (visu), headed by a vishayapati.

- Jana: The highest political unit was the tribe (jana), with several tribes like Bharatas, Matsyas, Yadus, and Purus.

The King (Rajan)

- The head of the kingdom (rajan) was primarily a tribal chief.

- His main duties were protecting the tribe, especially in warfare and maintaining law and order.

- Kings were often appointed by priests through the abhisheka ceremony.

Form of Government

- The government was tribal and militaristic, with no civil or territorial administration.

- The king’s power was not absolute; he was elected by the tribal assembly (samiti) and maintained by popular support.

Officials

- The king was supported by the purohita (priest), senani (army commander), gramani (village headman), and spasa (spies). Priests, particularly Vasishtha and Vishvamitra, played critical roles in advising kings and performing religious rituals.

Popular Assemblies

- Sabha and Samiti were two main assemblies that limited the king’s power.

- Both assemblies discussed a wide range of topics from war to religious matters. Women also participated in the deliberations.

Later Vedic Period (1000–500 B.C.)

Changes in Kingship and Administration

- Kingship became hereditary, and the concept of divine kingship appeared.

- The territorial concept of kingship emerged, leading to the formation of larger kingdoms (janapadas) and territories (rashtras).

- The power of assemblies like sabha and samiti diminished as they were dominated by nobles and Brahmins, excluding women.

Rise of Monarchies

- Kings began performing rituals such as the Rajasuya, Ashvamedha, and Vajapeya to legitimize their rule and authority.

- With increasing territories, the king’s influence grew, and taxation became common under officers such as the sangrihitri.

Evolution of Political Conflicts

- Inter-tribal and intra-tribal conflicts over land became common, marking a shift from the earlier period’s cattle raids. This led to larger political entities and the formation of early states.

Social Life

Early Vedic Period (1500–1000 B.C.)

Family and Kinship

- Society was primarily tribal and based on kinship.

- Family (kula) was the basic social unit, led by a patriarch. Joint families were common, and the birth of a son was highly desired.

Status of Women

- Women enjoyed a high status and participated in religious and social activities. Learned women like Lopamudra and Ghosa composed hymns. Swayamvara (marriage by choice) was common, and widow remarriage was allowed.

Social Divisions

- Early Vedic society was relatively egalitarian, with minor social divisions based on varna (color) and dasa (non-Aryans). Aryans and non-Aryans were often differentiated by skin color and language.

Later Vedic Period (1000–500 B.C.)

Varna System and Social Stratification

- Society evolved into a fourfold varna system, dividing people into Brahmins (priests), Kshatriyas (warriors), Vaishyas (merchants), and Shudras (servants).

- A hymn in the Purusha-Sukta described the origin of the varnas from the cosmic man (Purusha). Brahmins emerged from his mouth, Kshatriyas from his arms, Vaishyas from his thighs, and Shudras from his feet.

Decline of Women’s Status

- Women’s status declined in the Later Vedic period. They were excluded from public assemblies like sabha and were denied the right to inherit property. They became more dependent on their fathers, husbands, or sons.

Gotra System

- The gotra system, where people with the same gotra (ancestral lineage) could not marry, emerged during this period.

Economic Life

Early Vedic Period (1500–1000 B.C.)

Pastoral Economy

- The economy was primarily pastoral, with cattle rearing as the main occupation. Wealth was measured in terms of cows, and conflicts were often fought over cattle.

Agriculture and Other Occupations

- Although pastoralism dominated, agriculture was also practiced, albeit on a small scale. Barley was the main crop.

- Artisans like carpenters, chariot-makers, weavers, and smiths existed, but their role in the economy was secondary to cattle rearing.

Later Vedic Period (1000–500 B.C.)

Shift to Agriculture

- A transition occurred from a pastoral economy to an agrarian one. The use of iron tools helped clear forests and cultivate the fertile Ganga-Yamuna Doab.

- Agriculture became the primary occupation, with rice, barley, and wheat as the chief crops.

Introduction of Iron

- Iron technology played a significant role in transforming the economy. It enabled efficient farming practices, leading to surplus production.

Trade and Crafts

- Artisans became more specialized, with occupations such as potters, weavers, and jewelers. There was an increase in trade, and some sea-borne trade is indicated in the Later Vedic texts.

Use of Currency

- Though there was no formal coinage, krishnala and nishka served as units of currency, marking the early stages of a monetary system.

Religious Life and Evolution of Deities

Early Vedic Period (1500–1000 B.C.)

- The Vedic people worshipped natural forces, personified as gods, such as Indra (god of war and rain), Agni (god of fire), and Varuna (god of cosmic order).

- Sacrifices were central to religious practice, and priests played a crucial role in mediating between gods and humans.

Later Vedic Period (1000–500 B.C.)

- Religion became more complex, with rituals like Ashvamedha and Rajasuya gaining prominence.

- Deities like Prajapati (the creator), Vishnu, and Rudra gained importance, reflecting a shift from naturalistic to more abstract concepts of divinity.

Conclusion

The Vedic period marked a significant transition in Indian history. Politically, it evolved from a tribal system to larger monarchies. Socially, the rise of the varna system led to greater stratification, and the status of women declined. Economically, the shift from pastoralism to agriculture, aided by iron technology, laid the foundation for a more settled and productive society. Finally, religious practices and the pantheon of deities became more complex, aligning with the changes in political and social structures.

[…] challenge traditional justifications for sati. He demonstrated that Hindu scriptures, such as the Vedas and Dharmashastras, did not mandate or even condone the […]

[…] Vedic Age in India […]