For Prelims: Indian Feudalism, feudalism in india, feudalism in india upsc, feudalism in indian history, Indian Feudalism UPSC

For Mains: Indian Feudalism, feudalism in india, feudalism in india upsc

The concept of Indian Feudalism revolves around the socio-political and economic framework that emerged during the early medieval period, marked by significant transitions in land ownership, governance, and social hierarchies. Below, every aspect of Indian feudalism is elaborated with simplicity and clarity for better understanding.

*

Definition of Feudalism

Feudalism in India refers to a system where land ownership and control became the basis for social, economic, and political power. It introduced a hierarchical structure where feudal lords controlled large tracts of land and its produce while peasants worked the land in exchange for protection or tenancy rights. This system established a clear overlord-subordinate relationship, creating a new power dynamic. Feudalism emerged as an agrarian economy dominated by a few elites, whose authority was based on their control over land and resources.

*

Features of Indian Feudalism

#### 1\. Land and Land Rights

The foundation of Indian feudalism was based on land ownership and rights. The right to own and control land was concentrated in the hands of feudal lords, who were often beneficiaries of royal grants. These rights were not just economic but also tied to social status and power. Control over land determined the distribution of wealth and established a feudal hierarchy. Unlike previous systems, where land was communal or state-owned, feudalism created private and hereditary land rights.

#### 2\. Superior Rights of Feudal Lords

Feudal lords enjoyed superior rights over the land and its produce, allowing them to collect taxes or revenue from peasants. These rights often came through land grants, which transferred not just land but administrative and judicial powers to the grantee. Such rights enabled lords to dominate rural societies, acting as intermediaries between the king and the peasantry. This control over land also granted them authority over the labor and economic output of the land.

#### 3\. Revenue Appropriation

Revenue collection became a central feature of Indian feudalism. Landowners, granted authority by rulers, appropriated a significant portion of agricultural produce from the peasants. This revenue was used to maintain armies, construct infrastructure, and fund other activities. However, the burden of revenue often fell heavily on the peasants, leading to exploitation. The revenue system reflected a pyramidal structure where peasants were at the bottom, contributing to the sustenance of the feudal hierarchy.

#### 4\. Hereditary Rights

Landownership under feudalism often became hereditary, passing from one generation to the next within the same family or lineage. This hereditary right solidified the power of feudal lords and created a class of elites whose influence persisted over centuries. Such inheritance systems entrenched social inequalities, as wealth and power remained concentrated within specific families or castes. Over time, these hereditary rights became almost impossible to challenge or revoke.

#### 5\. Administrative and Judicial Powers

Feudal lords were granted administrative and judicial authority over their territories, making them autonomous rulers within their domains. They acted as judges, tax collectors, and military commanders, exercising control over both the land and its inhabitants. This decentralization of power weakened the central authority of the king and gave rise to local governance systems. These powers enabled feudal lords to consolidate their influence and maintain their dominance over the rural population.

#### 6\. Jayaskandhavaras (Victory Camps)

Jayaskandhavaras were military camps that also served as administrative and political centers for feudal lords. These camps were strategically established to protect their territories and oversee governance. Over time, these camps evolved into permanent settlements, further strengthening the power base of the feudal lords. The existence of such camps highlights the militarized nature of feudal society and the role of land in supporting armies and political control.

#### 7\. Feudal Titles

Feudal lords were often granted prestigious titles like _Thakur_, _Raja_, _Rao_, and _Rauts_. These titles symbolized their elevated status in society and their role as intermediaries between the king and the common people. Such titles were not just honorary but carried significant power and authority, reinforcing the hierarchical nature of feudalism. The use of these titles became a marker of prestige and a means to legitimize their dominance over land and its inhabitants.

#### 8\. Sub-Infeudation

Sub-infeudation refers to the practice of landowners leasing out parts of their land to other intermediaries, creating multiple layers of control. For instance, a feudal lord might grant a portion of their land to a vassal, who, in turn, could lease it to a tenant farmer. This system led to the emergence of a complex hierarchy of landed intermediaries. While it allowed for greater land utilization, it also increased the exploitation of peasants, who had to support multiple layers of authority.

*

Economic Implications of Feudalism

#### 1\. New Agrarian Structures

The introduction of feudalism brought about a significant reorganization of the agrarian economy. Land distribution shifted from communal ownership to hierarchical control, with feudal lords at the top. This system created a dependency where peasants worked on the land in exchange for protection or tenancy. The agrarian economy became the primary driver of economic activity, focusing on subsistence farming rather than trade or industrial growth.

#### 2\. Self-Sufficient Villages

Feudalism fostered the development of self-sufficient village economies. Villages became isolated units where agricultural produce met the needs of the local population. Trade and external interactions diminished, as most goods were produced and consumed locally. This self-sufficiency reduced economic integration and innovation, leading to stagnation in certain regions. However, it also ensured that basic needs were met within the community.

#### 3\. Decline of Urban Centers

The rise of feudalism coincided with the decline of urban centers. As economic activity became localized, the importance of cities as hubs of trade and culture diminished. Artisans and merchants, unable to sustain their livelihoods, migrated to rural areas or adopted agricultural practices. This decline weakened urban economies and cultural vibrancy, marking a significant shift from the cosmopolitanism of earlier periods.

#### 4\. Vishti (Forced Labor)

Forced labor, or vishti, became a hallmark of the feudal economy. Peasants were compelled to provide free or low-cost labor to feudal lords, often under harsh conditions. This labor was used for agricultural work, construction, or military purposes. Over time, forced labor reduced peasants to semi-serfs, stripping them of autonomy and deepening social inequalities. The prevalence of vishti highlights the exploitative nature of feudal systems.

#### 5\. Closed Economies

Feudalism led to the creation of closed economies, where production and consumption occurred within the same community. R.S. Sharma argued that self-sufficiency became a defining feature of feudal economies. This isolation limited trade, reduced specialization, and stifled economic growth. While it ensured basic sustenance, it also restricted innovation and broader economic integration.

#### 6\. Decline of Urban Economy

Under the feudal system, urban centers that once thrived as hubs of trade and culture faced significant decline. The agrarian focus of the economy meant less attention was given to trade and artisan activities, resulting in diminished urbanization. Artisans, merchants, and other urban dwellers often migrated to rural areas or shifted to agriculture, further weakening the urban economy. This decline in urban activity also led to reduced innovation and cultural exchange, marking a stark contrast to earlier periods of urban prosperity.

#### 7\. Growth of Self-Sufficient Rural Economy

The feudal system emphasized local production, creating self-sufficient rural economies. Villages produced food, textiles, and tools to meet their own needs, minimizing dependence on external trade. While this self-reliance ensured stability within villages, it also curtailed economic diversification and growth. The limited interaction between regions stifled innovation and exchange of ideas, contributing to a more static economic structure.

#### 8\. Agricultural Dominance

Agriculture became the backbone of the feudal economy, with landowners extracting surplus produce from peasants. The emphasis on land-based wealth fostered agricultural expansion, including the clearing of new lands for cultivation. However, the heavy reliance on agriculture made the economy vulnerable to climatic changes and crop failures, often leading to economic instability. Despite its dominance, the agrarian system left little room for industrial or commercial growth

#### 9\. Development of Hierarchical Land Structures

Indian feudalism saw the emergence of a hierarchical land ownership system. At the top were feudal lords, including Brahmanas, military officers, and other donees, who controlled vast estates. Below them were vassals and intermediaries who managed smaller portions of land. At the base were tenant farmers and peasants who worked the land and paid a portion of their produce as rent. This structure ensured the dominance of a few elites while marginalizing the majority of the rural population. Over time, this stratification created enduring socio-economic inequalities.

#### 10\. Shift to a Closed Economy

The feudal period witnessed a marked shift from a trade-based economy to a closed, localized one. Villages became self-contained units, producing goods primarily for their own consumption. This change reduced the scope of inter-regional trade and cultural exchange, limiting economic diversity and innovation. However, it also ensured that communities could survive independently, even during periods of political instability. This shift had long-term implications for India’s economic trajectory, particularly its late industrialization compared to other regions.

*

Political Implications of Feudalism in India

#### 1\. Land-Based Power

Under feudalism, political authority was intrinsically tied to land ownership. Feudal lords derived their power from their control over land and its produce. This shift marked a departure from earlier systems, where power was centralized under kings or emperors. Land-based power structures decentralized governance and created localized centers of authority, significantly altering the political landscape.

#### 2\. Decentralized Polity

The feudal system fragmented political power, leading to the emergence of multiple small kingdoms or principalities. Each feudal lord acted as a semi-independent ruler, controlling their territory and resources. This decentralization weakened the central authority and led to frequent conflicts among feudal lords. While it provided localized governance, it also created instability and hindered broader political integration.

#### 3\. Feudal Armies

The concept of a standing army was replaced by feudal militias, maintained by individual lords. These armies were funded through revenue collected from land and were often loyal to their lords rather than the king. This shift diluted the central authority's control over military power and created a fragmented defense system. Feudal armies were instrumental in protecting territories but also contributed to internal conflicts and rivalries.

#### 4\. Weakened Bureaucracy

Feudalism diminished the role of centralized bureaucracy, as administrative powers were transferred to feudal lords. This decentralization made governance more localized but also less efficient. The absence of a strong bureaucratic framework hindered the implementation of uniform policies and created disparities in governance. Over time, the weakened bureaucracy contributed to the overall decline of centralized empires.

#### 5\. Hierarchy of Feudal Lords

The political structure during the feudal period was dominated by a hierarchy of feudal lords. At the base were the peasants, who worked the land, followed by intermediaries like vassals and knights, and finally the king at the top. This pyramid of authority ensured that power and resources were concentrated at higher levels. While this structure provided localized governance, it also led to fragmentation and frequent conflicts among lords, weakening the central authority.

#### 6\. Erosion of Centralized Power

Feudalism caused the central authority of kings and emperors to erode significantly. As land was granted to feudal lords with administrative and military powers, the central government lost its control over large parts of the kingdom. This decentralization made it difficult for rulers to enforce laws, collect taxes, or maintain a standing army, leading to political fragmentation. Over time, this erosion of centralized power contributed to the decline of large empires like the Guptas.

#### 7\. Loss of Bureaucratic Efficiency

Feudalism led to a significant decline in the efficiency of centralized bureaucracies. With administrative powers devolved to feudal lords, the central government lost its ability to implement uniform policies or collect taxes effectively. This decentralization created disparities in governance, with different regions operating under varying sets of rules. Over time, this inefficiency weakened the ability of rulers to respond to crises or coordinate large-scale projects, such as infrastructure development or military campaigns.

#### 8\. Rise of Regional Kingdoms

The fragmentation of central authority gave rise to numerous regional kingdoms, each with its own feudal hierarchy. These kingdoms, while autonomous, often maintained nominal allegiance to a central ruler or overlord. This political fragmentation encouraged regionalism, fostering the growth of distinct cultures, languages, and traditions. While this diversification enriched Indian society, it also contributed to political instability and frequent conflicts among neighboring states.

*

Social Implications of Feudalism in India

#### 1\. New Social Hierarchies

Feudalism introduced a new basis for social status, tied to land ownership rather than caste alone. Feudal lords, regardless of their caste background, rose in prominence due to their control over land. This shift blurred traditional caste lines and created a more complex social hierarchy. However, it also reinforced social inequalities, as landless peasants were marginalized and subjected to exploitation.

#### 2\. Rise of Kayastha Caste

The administrative needs of the feudal system led to the emergence of the Kayastha caste, comprising scribes and record-keepers. These individuals gained prominence due to their role in managing land grants and revenue records. Over time, the Kayasthas became a distinct caste group, highlighting how feudalism reshaped social structures. Their rise illustrates the adaptability of Indian society in response to changing economic and political conditions.

#### 3\. Blurring of Caste Distinctions

The feudal system blurred traditional caste distinctions, particularly between the Vaisyas and Shudras. Declining trade and craft industries reduced the prominence of Vaisyas, while many Shudras adopted agriculture and rose in social status. This fluidity in caste dynamics challenged the rigid varna system, leading to the proliferation of new caste groups based on professions, regions, or land ownership. This social reorganization reflected the changing economic and political landscape of the feudal period.

#### 4\. Peasantization of Tribes

Feudalism also brought about the peasantization of tribal communities. As land grants expanded, many tribes abandoned their traditional nomadic or hunting lifestyles and took to settled agriculture. This transition integrated tribal groups into the feudal economy and caste hierarchy, altering their socio-cultural identities. While this shift increased agricultural productivity, it also marginalized the autonomy of tribal groups, subjecting them to exploitation by feudal lords.

#### 5\. Emergence of Kayasthas

The Kayasthas emerged as a new social group during the feudal period, primarily due to their roles as scribes and administrators. As land grants became widespread, the need for record-keeping and revenue management grew, leading to the rise of this caste. Over time, the Kayasthas gained significant socio-political prominence, demonstrating how feudalism reshaped the caste structure and created new opportunities for social mobility.

#### 6\. Vishti (Forced Labor) and Semi-Serfdom

The practice of vishti, or forced labor, was a significant feature of Indian feudalism. Peasants were compelled to provide unpaid or low-paid labor to feudal lords, reducing them to the status of semi-serfs. This exploitation extended beyond agriculture, as peasants were often required to perform tasks like construction, transportation, and maintenance. Vishti highlighted the harsh realities of feudal society, where the peasantry bore the brunt of economic and social inequalities.

#### 7\. Strengthening of Brahmanical Influence

Feudalism significantly bolstered the influence of Brahmanas, who were often recipients of land grants. These grants gave Brahmanas not only economic power but also administrative and judicial authority. As custodians of land and local governance, Brahmanas reinforced Brahmanical ideologies and rituals in rural areas. Temples, often built on these lands, became centers of social and cultural life, further strengthening their role in shaping society.

#### 8\. Impact on Women

The feudal system also affected women, particularly in rural societies. With the rise of land-based hierarchies, women’s roles became increasingly tied to the domestic sphere. While women from elite classes sometimes managed estates or performed administrative duties, the majority of women faced restrictions on their mobility and participation in public life. Dowry systems and patriarchal norms were further entrenched during this period, reflecting the broader inequalities of feudal society.

*

Factors for rise of Indian Feudalism

#### 1\. Gupta and Post-Gupta Period

The roots of Indian feudalism lie in the Gupta and post-Gupta periods, where land grants became a prevalent practice. Rulers began granting land to Brahmanas, temples, and military officers to consolidate power and reward loyalty. This system marked a shift from centralized governance to localized control, setting the stage for the feudal hierarchy. The economic decline during this period, including reduced trade and urban activity, further accelerated the feudalization process.

#### 2\. Land Grants and Power Fragmentation

The expansion of land grants under the Satavahanas and later dynasties contributed to power fragmentation. As more land came under the control of feudal lords, the central authority weakened. This decentralization gave rise to small kingdoms and principalities, each governed by its own feudal hierarchy. While this system enabled localized governance, it also created political instability and frequent conflicts among competing rulers.

#### 3\. Decline of Trade and Urban Centers

The rise of feudalism was closely linked to the decline of trade and urban centers during the early medieval period. Starting around the 4th century CE, long-distance trade networks began to disintegrate due to political instability and the collapse of centralized empires like the Guptas. This decline reduced the economic importance of cities, shifting the focus to rural agrarian economies. As trade diminished, merchants and artisans moved to villages, where they integrated into the feudal system, often as tenants or laborers.

#### 4\. Fragmentation of Power

The decline of centralized empires after the Gupta period led to the fragmentation of political power. Regional rulers and local chieftains filled the vacuum, creating a patchwork of small, autonomous kingdoms. These rulers relied on land grants to maintain loyalty and governance, further entrenching feudal structures. This fragmentation marked the transition from a unified empire to a decentralized political landscape dominated by feudal lords.

*

Why Indian Feudalism Declined?

#### 1\. Foundation of the Delhi Sultanate

The establishment of the Delhi Sultanate in 1206 marked the beginning of the decline of feudalism in India. The Sultanate introduced centralized governance, undermining the power of feudal lords. The iqta system replaced hereditary land grants with non-hereditary assignments, ensuring that land revenue remained under the control of the state. This shift disrupted the feudal hierarchy and reasserted the authority of the central government.

#### 2\. Growth of Trade and Cash Economy

The revival of trade and the emergence of a cash economy played a crucial role in the decline of feudalism. By the 10th century, merchant guilds and trade networks regained prominence, connecting India to global markets. The use of coinage and monetary transactions reduced the dependence on land-based wealth, weakening the feudal system. This economic transformation laid the groundwork for a more diversified and dynamic economy.

#### 3\. Technological and Agricultural Advancements

Advancements in agriculture and technology further diminished the relevance of feudalism. Improved irrigation techniques, plowing methods, and crop varieties increased agricultural productivity, reducing the need for forced labor. These innovations empowered peasants and undermined the dominance of feudal lords, contributing to the gradual disintegration of the feudal structure.

#### 4\. Emergence of Merchant Guilds

The revival of trade in the later medieval period was driven by the emergence of merchant guilds, such as the Ayyavole and Manigramam in South India. These guilds facilitated inter-regional and international trade, connecting India to markets in the Middle East, Southeast Asia, and East Asia. The growing importance of commerce diminished the dominance of feudal lords, as wealth became increasingly tied to trade and industry rather than land ownership.

#### 5\. Introduction of the Iqta System

The Delhi Sultanate’s iqta system played a pivotal role in dismantling the feudal hierarchy. Unlike feudal land grants, iqtas were non-hereditary assignments given to officials in exchange for administrative and military services. This system ensured that land and revenue remained under the control of the central government, reducing the autonomy of local lords. Over time, the iqta system centralized power and revenue collection, weakening the feudal model.

#### 6\. Technological Innovations

Advancements in technology, particularly in agriculture, undermined the feudal system. The introduction of new irrigation methods, improved plowing techniques, and the use of high-yield crop varieties increased agricultural productivity. These innovations reduced the reliance on forced labor and tenant farming, empowering peasants and eroding the economic dominance of feudal lords. The gradual shift towards a cash economy further weakened the feudal structure, paving the way for more modern economic systems.

Comparison of Indian Feudalism with European Feudalism

Feudalism, as a socio-economic system, developed in both India and Europe but exhibited significant differences due to distinct ecological, technological, and social conditions. While some similarities can be drawn, as pointed out by scholars like R. S. Sharma, the differences are more pronounced, making it necessary to analyze the two systems independently.

*

Similarities Between Indian and European Feudalism

1. Rise of Intermediaries and Land Hierarchies

- Both Indian and European feudalism were characterized by the rise of intermediaries who controlled land and extracted revenue from peasants. These intermediaries acted as a buffer between the rulers and the peasantry.

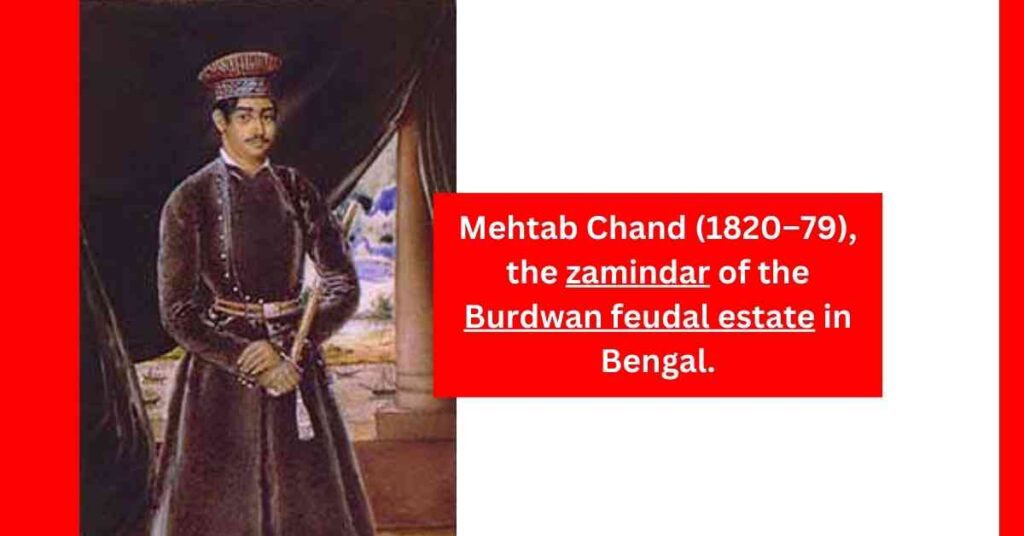

- In Europe, this class was comprised of knights, lords, and barons, while in India, they included feudal lords, zamindars, and temple grantees. R. S. Sharma drew parallels between these groups, suggesting that the hierarchical control of land was central to both systems.

2. Subjection of Peasants

- In both regions, peasants were subjected to the authority of landowners, often losing control over their produce and labor. This created a system of exploitation, with European serfs and Indian tenant farmers facing similar challenges.

- Sharma argued that the granting of land by the state to intermediaries was crucial in subjugating peasants, drawing parallels with serfdom in Europe.

3. Impact of Invasions

- External invasions played a pivotal role in shaping the feudal structure in both regions. The Arab invasions in Europe and the Hun invasions in India coincided with the beginning of feudalism. These invasions disrupted existing socio-political structures and facilitated the rise of feudal hierarchies.

- Scholars like B. N. S. Yadava highlighted this similarity, emphasizing the role of invasions in creating fragmented political and economic landscapes.

4. Peasant Rebellions

- In both systems, the oppressive nature of feudalism led to sporadic peasant uprisings. While Europe witnessed large-scale rebellions like the English Peasants' Revolt of 1381, evidence of such uprisings in India is scarce. However, R. S. Sharma cited the example of the Kaivarta revolt in Bengal during the 11th century, where boatmen and cultivators resisted feudal oppression.

An European Feudal Lord

*

Differences Between Indian and European Feudalism

#### 1\. Ecological Conditions

- Europe: Western Europe had a shorter agricultural season, with only four months of sunshine. This made farming highly labor-intensive, as all agricultural activities—plowing, sowing, harvesting, and storing—had to be completed within a limited time frame. The low seed-to-yield ratio (1:2.5) further necessitated intensive labor. To ensure labor availability, peasants were tied to the land, giving rise to serfdom.

- India: India enjoyed nearly ten months of sunshine, allowing agricultural activities to be spread out over a longer period. The fertile topsoil, replenished annually by monsoons, did not require deep plowing. Indian peasants could produce more with less effort, with a seed-to-yield ratio of 1:16. Many regions in India produced two crops annually, a feat unknown in Europe until the 19th century. This higher productivity reduced the need for tied labor, making Indian feudalism less labor-intensive.

*

#### 2\. Technological Context

- Europe: The agricultural technology in medieval Europe was rudimentary and labor-intensive. Tools like the wooden plow required significant manpower to till the heavy clay soils. The lack of effective irrigation systems also made farming dependent on seasonal rainfall. Technological breakthroughs were slow, and transformation in agriculture began only with the advent of modern tools in the 12th century.

- India: Indian farmers benefited from advanced agricultural tools and techniques. The humped Indian bull was better suited for plowing, as its anatomy allowed the plow to rest securely on its shoulders. Irrigation systems, including wells, tanks, and canals, were well-developed, ensuring consistent water supply. These technological advantages allowed Indian peasants to maintain control over their labor and land, reducing their dependency on feudal lords.

*

#### 3\. Nature of Labor Use

- Europe: Labor was directly tied to agricultural production. Serfs were bound to the land and required to work on their lord’s fields before attending to their own. This system ensured that feudal lords retained control over the entire agricultural process.

- India: Labor in India was generally not tied to production in the same way. Peasants retained control over their labor and were required to pay a portion of their produce as revenue. Forced labor (_begar_) in India was primarily used for non-productive activities, such as carrying goods or providing services to the zamindar, rather than for cultivation.

*

#### 4\. Manorial System

- Europe: The manorial system was central to European feudalism. A manor was a self-contained unit with agricultural fields, a manor house, and peasant dwellings. Lords exercised direct control over the land and its inhabitants, dictating both production and distribution.

- India: The Indian system lacked a comparable manorial structure. Villages operated as self-sufficient units but were not directly controlled by feudal lords in terms of production. The role of Indian feudal lords was primarily to collect revenue and enforce administrative control, with less interference in the day-to-day agricultural activities of peasants.

*

#### 5\. Transformation of the System

- Europe: Feudalism in Europe gradually transitioned into capitalism. The resolution of tensions over labor control led to agricultural innovations and increased market orientation. By the 12th century, capitalist tendencies began to emerge, leading to the eventual decline of the feudal order.

- India: In India, the tension over revenue collection did not lead to significant changes in the production system. The feudal structure persisted until the colonial period, and its transformation into a market-oriented economy began only in the 19th and 20th centuries under British rule. Unlike Europe, feudalism in India was replaced by colonial capitalism rather than indigenous capitalist development.

*

#### 6\. Role of Colonialism

- Europe: European feudalism was succeeded by capitalism, which fueled colonial expansion. Colonialism became an extension of Europe’s capitalist economy, with colonies providing raw materials and markets for finished goods.

- India: Feudalism in India was disrupted by colonialism, which introduced new economic systems and policies. The British colonial administration replaced traditional feudal structures with zamindari and ryotwari systems, fundamentally altering the agrarian economy. However, this transition was externally driven and did not follow the organic evolution seen in Europe.

*

[](https://learnpro.graphy.com/allcourses)

Indian feudalism, with its complex interplay of land ownership, social hierarchy, and political decentralization, remains a pivotal topic in understanding early medieval India. While it shared similarities with European feudalism, its unique ecological, social, and economic conditions set it apart. The rise and decline of feudalism illustrate the dynamic nature of Indian history, shaped by internal transformations and external influences. By examining these aspects, we gain valuable insights into the evolution of Indian society and its enduring legacies.

#### Other Useful Notes:

##### Ancient History

- [Harappan Civilization : Date, Extent, and Characteristics](https://learnpro.in/harappan-civilization/)

- [Paleolithic Age in India](https://learnpro.in/paleolithic-age-in-india/)

- [Mesolithic Rock Paintings in India](https://learnpro.in/mesolithic-rock-paintings-in-india-insights-into-prehistoric-life/)

- [Neolithic Age in India](https://learnpro.in/neolithic-age-in-india/)

- [Vedic Age in India](https://learnpro.in/vedic-age-in-india/)

- [Megalithic culture in India](https://learnpro.in/megalithic-culture-in-india/)

- [Expansion of Aryans in India: Migration, Settlement, and Cultural Evolution](https://learnpro.in/expansion-of-aryans-in-india-migration-settlement-and-cultural-evolution/)

- [Formation of States (Mahajanapadas): Republics and Monarchies](https://learnpro.in/formation-of-states-mahajanapadas-republics-and-monarchies/)

- [Jainism : An Overview of Ancient Indian Religions](https://learnpro.in/jainism/)

- [Buddhism – An Overview of Ancient Indian Religions](https://learnpro.in/buddhism/)

- [Chandragupta Maurya](https://learnpro.in/chandragupta-maurya/)

- [Iranian and Macedonian Invasions of India and Their Impact](https://learnpro.in/iranian-and-macedonian-invasions-of-india-and-their-impact/)

- [Mauryan Art, Architecture, and Sculpture : 4th Century BC Marvels (PDF Download](https://learnpro.in/mauryan-art-architecture-and-sculpture/)

- [Megasthenes’ Indika](https://learnpro.in/megasthenes-indika/)

- [Mauryan Empire: Foundation and Expansion](https://learnpro.in/mauryan-empire-foundation-and-expansion/)

- [Chanakya’s Arthashastra: A Book on Ancient Indian Statecraft](https://learnpro.in/chanakyas-arthashastra-a-book-on-ancient-indian-statecraft/)

- [Archaeological Sources: Excavation Epigraphy, Numismatics](https://learnpro.in/archaeological-sources-exploration-excavation-and-epigraphy/)

- [Prehistory and Proto-history : A detailed Analysis](https://learnpro.in/prehistory-and-proto-history-in-indian-history/)

##### 2\. Medieval History

- [Early Medieval India (750-1200) – A detailed Overview](https://learnpro.in/early-medieval-india-750-1200-introduction/)

- [Chola Empire (9th -13th century AD): Administration, Local Govt., Village Economy, Society](https://learnpro.in/chola-empire/)

##### 3\. Modern History

- [European Penetration in India- The Portuguese](https://learnpro.in/european-penetration-in-india-the-portuguese/)

- [Entry of Europeans and Struggle for Supremacy in India](https://learnpro.in/entry-of-europeans-and-struggle-for-supremacy-in-india/)

- [Raja Ram Mohan Roy: The Father of Modern India](https://learnpro.in/raja-ram-mohan-roy/)

##### 4.World History

- [Aristotle: The Timeless Philosopher Who Shaped Western Thought](https://learnpro.in/aristotle/)

- [Achaemenid Empire (550 BCE to 330 BCE): A brief Introduction](https://learnpro.in/achaemenid-empire/)

- [The Renaissance in Italy 14th Century: A Rebirth and Transformation](https://learnpro.in/the-renaissance-in-italy-14th-century-a-rebirth-and-transformation/)

- [The European State System: Evolution, Characteristics, and Global Influence](https://learnpro.in/european-state-system/)

- [The Thirty Years’ War: A Pivotal Chapter in European History](https://learnpro.in/the-thirty-years-war/)

- [Napoleon Bonaparte (1769–1821): Architect of Modern Europe](https://learnpro.in/napoleon-bonaparte/)

- [Otto von Bismarck (1815–1898): The Iron Chancellor and Architect of German Unification](https://learnpro.in/bismarck/)

- [Unification of Germany: The Birth of a Nation](https://learnpro.in/unification-of-germany-the-birth-of-a-nation/)

- [The Holy Roman Empire: A Complex Political Entity](https://learnpro.in/holy-roman-empire/)

- [The American Revolution : Factors leading to revolution](https://learnpro.in/the-american-revolution-factors-leading-to-revolution/)