February 24, 2026 3:04 am

Background to the Battle of Buxar: Rule of Mir Jafar and Mir Kasim (1761–1763)

Decline of Mir Jafar’s Authority and the Rise of Mir Kasim

After the Battle of Plassey in 1757, Mir Jafar was installed as the Nawab of Bengal with the full support of the British East India Company. However, the relationship soon began to deteriorate. The Company became increasingly demanding, and Mir Jafar found it difficult to meet their expectations, especially financial payments promised after the Plassey settlement. His inability to fulfil the financial obligations, coupled with the exhausted state treasury, created deep resentment among Company officials.

At the same time, Mir Jafar’s administrative inefficiency and his growing disinterest in governance made him unpopular among the people of Bengal. The situation further complicated after the death of Miran, Mir Jafar’s son, leading to a succession dispute between Mir Kasim (his son-in-law) and Miran’s minor son.

Given the circumstances, the Company began to search for a more competent and pliable successor. Mir Kasim offered better financial assurances, which proved decisive. The Company chose to back his claim to the throne, especially under the leadership of Henry Vansittart, who became Governor of Bengal after Clive’s departure in 1760.

Treaty between Mir Kasim and the Company (1760)

A formal treaty was signed in 1760 between Mir Kasim and the British East India Company. Its provisions reflected both political alignment and economic ambition:

- Mir Kasim would cede the districts of Burdwan, Midnapur, and Chittagong to the Company.

- The Company would receive half the revenue from the chunam (lime) trade in Sylhet.

- He agreed to pay all pending dues to the Company.

- A sum of ₹5 lakh was promised for Company war expenses in southern India.

- It was agreed that the Company’s friends and enemies would also be Kasim’s friends and enemies, showing an alliance-based understanding.

- Tenants from Nawab’s territory could not settle in Company lands, and vice versa.

Under pressure, Mir Jafar resigned, and a pension of ₹1,500 per annum was fixed for him. Thus, Mir Kasim became the Nawab of Bengal.

Mir Kasim’s Assertive Administration (1761–1763)

Mir Kasim, unlike his predecessor, had both administrative ability and political ambition. He was regarded as the most capable successor of Alivardi Khan. Refusing to be a puppet in the hands of the British, he made deliberate efforts to establish an independent and efficient administration.

Some of his major steps included:

- Shifting the capital from Murshidabad to Munger (Bihar), thereby physically distancing his seat of power from the British base at Calcutta.

- Reorganising the bureaucracy by appointing competent and loyal officials.

- Setting up factories for arms manufacture and strengthening the military infrastructure.

- Training the army on European lines, making it better prepared to resist any external intervention.

- Realising state arrears to replenish the empty treasury.

- Abolishing all internal duties to neutralise the British misuse of dastaks and provide equal opportunities to Indian traders.

The abolition of internal duties was a direct challenge to British commercial dominance. While Indian merchants welcomed this step, the British strongly protested, demanding preferential trade privileges.

Despite repeated complaints from Governor Vansittart, Mir Kasim refused to reduce his military strength or reverse his policies. His assertion of autonomy, both economically and politically, increasingly frustrated the Company.

Breakdown of Relations and British Retaliation

Mir Kasim’s reforms were aimed at building a sovereign and self-sufficient Bengal. However, these very measures—economic equality for native traders, independent military build-up, administrative centralisation—were seen by the Company as acts of defiance.

Ultimately, the British chose to retaliate. In 1763, they deposed Mir Kasim and reinstalled Mir Jafar, the compliant former Nawab. This decision pushed the conflict toward a full-scale military confrontation, setting the stage for the Battle of Buxar in 1764.

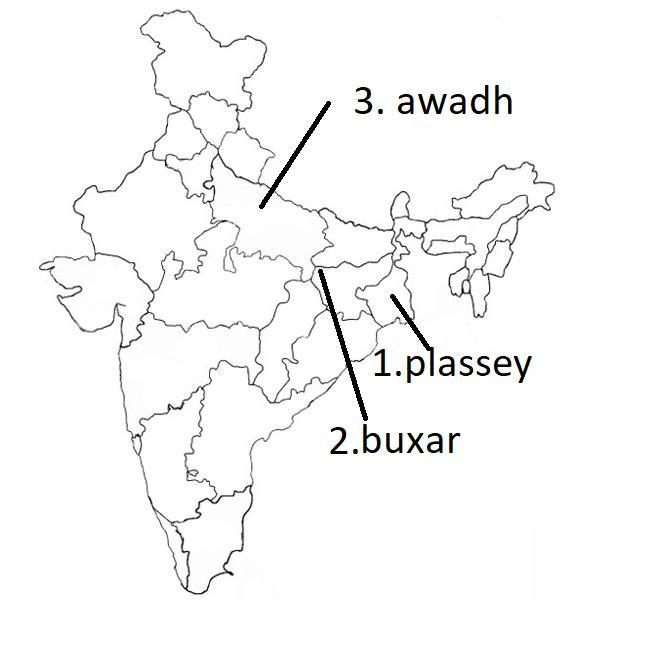

The Battle of Buxar (1764)

Background and Build-Up to the Battle

The roots of the Battle of Buxar can be traced directly to the aftermath of the Battle of Plassey (1757) and the appointment of Mir Kasim as Nawab of Bengal. Initially installed with the support of the British East India Company in 1760, Mir Kasim was expected to remain a compliant and cooperative ruler. However, once in power, he challenged British expectations and took a series of administrative, military, and economic steps that were seen as hostile by the Company.

Reforms and Assertion by Mir Kasim

Mir Kasim initiated several reforms aimed at strengthening the financial and administrative backbone of his state. These included:

- Reduction in palace and administrative expenditure

- Manufacture of firelocks and guns

- Regular payment of salaries to officials and troops

- Imposition of new taxes

- Shifting the capital from Munger to Murshidabad

These actions disturbed the entrenched interests of the Company’s officers and provoked annoyance among British administrators in Bengal.

One of his most bold and controversial decisions was the abolition of internal taxes altogether. This step was taken in response to the rampant misuse of dastaks (free trade passes) by British officials, which allowed them to dominate trade while Indian merchants had to pay heavy duties. This move aimed to level the playing field between British and Indian traders, but it infuriated the Company, which was unwilling to surrender its commercial advantages.

Tensions over Bihar Revenue and the Role of Ram Narayan

Another major flashpoint arose in Bihar. Ram Narayan, the deputy governor of Bihar, repeatedly refused to submit revenue accounts despite orders from Mir Kasim. This open defiance was encouraged by the English officials in Patna, particularly because Ram Narayan was viewed as a reliable ally by the Company.

Mir Kasim saw this as a direct challenge to his authority, and the already strained relationship between him and the British further deteriorated.

Military Confrontation Begins: The 1763 Skirmishes

The conflict over transit duties eventually escalated into open warfare in 1763. Between June and September 1763, three battles were fought between the British and Mir Kasim’s forces. In all these encounters, the British emerged victorious, severely weakening Mir Kasim’s position.

Following these defeats, Mir Kasim fled to Allahabad, seeking refuge and political support to counter the Company’s growing power.

Formation of the Triple Alliance: Mir Kasim, Shuja-ud-Daulah, and Shah Alam II

At Allahabad, Mir Kasim began diplomatic negotiations to form a broad alliance against the British. He approached two key figures:

- Shuja-ud-Daulah, the Nawab of Awadh (Oudh)

- Shah Alam II, the Mughal emperor

Shah Alam II, who had been in the eastern region since 1758, had fled the unstable and faction-ridden politics of Delhi when he was still a crown prince. He had hoped to carve out an independent power base in eastern India. After the assassination of his father Alamgir II in 1759, he declared himself emperor and appointed Shuja-ud-Daulah as his wazir.

Although reluctant at first, both Shah Alam and Shuja eventually agreed to support Mir Kasim after prolonged and complex negotiations. Their participation in the conflict was secured through strategic promises:

- Shuja-ud-Daulah was promised the province of Bihar and its treasury, along with a payment of ₹30 million, on the condition of British defeat.

- The alliance aimed to reassert Mughal influence, contain the expansion of the British, and restore indigenous control over eastern India.

Thus, by late 1763 and early 1764, the stage was set for a major military confrontation between the British East India Company and a combined Indian front led by Mir Kasim, Shuja-ud-Daulah, and Shah Alam II—a conflict that would culminate in the Battle of Buxar in October 1764.

The Battle of Buxar (23 October 1764)

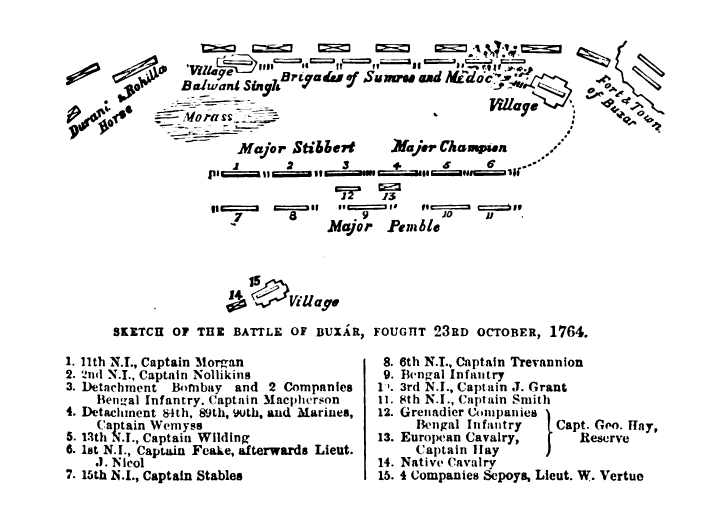

The Battle of Buxar was fought on 23 October 1764 at Katkauli, approximately 6 kilometers from Buxar, located then within the territory of Bengal. The confrontation took place between the British East India Company, led by Major Hector Munro, and the combined forces of:

- Mir Qasim, the deposed Nawab of Bengal

- Shuja-ud-Daulah, the Nawab of Awadh

- Shah Alam II, the Mughal Emperor

The battle was the culmination of a political and military struggle that had been intensifying since the British consolidated power after the Battle of Plassey. The alliance of the three Indian rulers was formed with the primary objective of curbing British influence in Bengal and reasserting indigenous sovereignty.

Strategic Intentions Behind the Alliance

After ascending to the Mughal throne, Shah Alam II aimed to revive the authority of the Mughal Empire by reclaiming control over key eastern territories, particularly Bengal, Bihar, and Orissa. These territories were historically under Mughal suzerainty but were now under the growing influence of the East India Company.

Shuja-ud-Daulah, who provided shelter to Shah Alam II, also sought to curb British supremacy in Bengal and saw in Mir Qasim and the emperor valuable allies. The primary cause of the conflict was the desire of these rulers to reclaim Bengal and reduce the Company’s power.

However, this tripartite alliance was plagued by internal divisions from the beginning:

- Shah Alam II and Shuja-ud-Daulah were often at odds, leading to political friction within the camp.

- Mir Qasim, having suffered successive defeats in 1763, was now reluctant and cautious in committing to full-scale battle.

- The lack of coordination, unified command, and shared military strategy between the allies significantly weakened their overall effectiveness.

Nature and Outcome of the Battle

Despite their large numerical strength, the Indian allies were decisively defeated by the well-trained and disciplined army of the East India Company. The Indian forces represented a typical 18th-century segmentary army, heavily dependent on decentralized feudal loyalties, irregular payments, and poor logistics. In contrast, the British army operated under a centralized and unified command, with better equipment, training, and coordination.

The outcome of the battle was a clear and decisive British victory.

- Mir Qasim, after the defeat, fled toward the northwest and eventually died in obscurity.

- Shah Alam II, recognizing the strength of the British and the hopelessness of resistance, deserted Shuja-ud-Daulah and sought shelter in the British camp.

- Shuja-ud-Daulah, although initially determined to resist, continued sporadic conflict until 1765, after which he fled to Rohilkhand, marking the collapse of the opposition.

The Battle of Buxar proved to be a more fiercely contested battle than Plassey. Unlike Plassey, which was won primarily through diplomacy and betrayal, Buxar was a military engagement fought openly on the battlefield and demonstrated the clear superiority of British arms and strategy.

At the time of the battle, Robert Clive was in England. The military victory was achieved under Major Hector Munro, but the aftermath was politically managed by Clive, who returned to India in 1765, now styled as Lord Clive, and resumed office as the Governor-General of Bengal.

The battle marked a critical turning point in British ascendancy in India. It conclusively demonstrated that the East India Company was no longer just a trading body, but a major military and political power capable of defeating a combined Indian imperial force.

The victory at Buxar laid the foundation for political treaties that would follow and mark the beginning of direct Company administration, starting with the Treaty of Allahabad in 1765.

Treaty of Allahabad (1765)

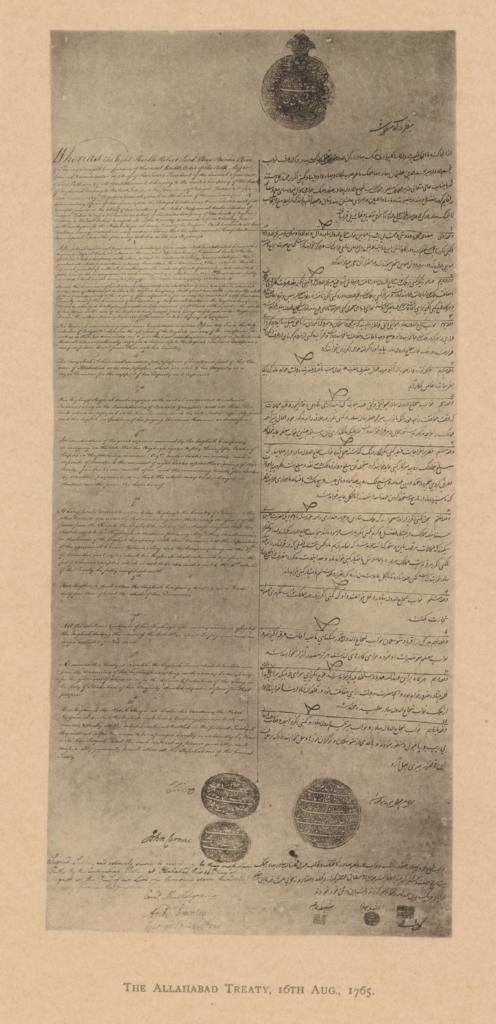

The Treaty of Allahabad, signed in August 1765, was a watershed moment in Indian history, formalizing the beginning of Company rule in India through diplomatic, fiscal, and territorial arrangements. It was orchestrated by Lord Robert Clive, who had returned to India after the Battle of Buxar and was now serving as the Governor of Bengal.

Two separate treaties were signed at Allahabad — one with the Mughal Emperor Shah Alam II, and another with the Nawab of Awadh, Shuja-ud-Daulah.

1. Treaty between the East India Company and Mughal Emperor Shah Alam II

Shah Alam II, who had sought British protection after the defeat at Buxar, agreed to a formal settlement with the East India Company. Under this treaty:

- The Mughal Emperor granted the Diwani rights — the fiscal authority to collect land revenue and administer civil justice — to the Company over the provinces of Bengal, Bihar, and Orissa.

- This effectively meant that the Company would now collect taxes directly from the people of these three provinces, making it the real administrative authority.

- The Nizamat rights — which included police and judicial functions — were retained in theory by the Nawab of Bengal, creating a dual structure that allowed indirect British control.

- In return for these rights, the Company agreed to pay an annual tribute of ₹26 lakhs to the Emperor.

- The districts of Kora and Allahabad were restored to the Mughal Emperor, which had earlier been under Shuja-ud-Daulah.

This treaty legalised the Company’s control over Bengal, Bihar, and Orissa and marked the beginning of dual governance, where the Company exercised power without formal responsibility, using the emperor’s name as a cover of legitimacy.

2. Treaty between the East India Company and Nawab of Awadh Shuja-ud-Daulah

The second treaty was concluded with Shuja-ud-Daulah, the Nawab of Awadh, who had also fought against the Company at Buxar but was restored to his throne under British terms.

Key provisions of this treaty included:

- Territorial adjustment: The province of Awadh was returned to Shuja-ud-Daulah, but Allahabad and Kora were taken from him and handed over to the Mughal Emperor.

- War indemnity: Shuja was made to pay ₹53 lakhs as war indemnity to the British East India Company.

- Banaras settlement: The Zamindari of Banaras was granted to Balwant Rai.

- Posting of a British Resident: An English Resident was to be stationed at Lucknow, whose expenses were to be borne by the Nawab.

- Commercial privileges: The Company received duty-free trading rights within Awadh — a privilege that would later create serious tensions and eventually lead to the annexation of Awadh in 1856.

- Military obligations: An offensive and defensive alliance was concluded. The Nawab promised to provide free military aid to the Company in case of war, while the Company agreed to provide troops for the defence of Awadh’s frontiers, with maintenance expenses to be paid by the Nawab.

Strategic Implications and Long-Term Impact

The Treaty of Allahabad had deep implications for the future of British rule in India:

- It marked the formal beginning of Company’s political authority in India under the guise of legal Mughal endorsement.

- The Mughal emperor became a nominal sovereign, whose name would henceforth legitimize the Company’s rule, while having no real power.

- The Resident at Murshidabad, initially a diplomatic observer, gradually assumed real administrative control by 1772, thereby institutionalising the Company’s indirect rule in Bengal.

Lord Clive, who negotiated both treaties, had clear strategic objectives:

- He refused to annex Awadh, despite military superiority, because doing so would have forced the Company to defend an extensive and vulnerable land frontier from Afghan and Maratha incursions.

- Instead, by restoring Awadh under a British-controlled treaty, Clive converted it into a buffer state, friendly to the Company and shielding Bengal from northwestern threats.

- His settlement with Shah Alam II ensured that the emperor would serve as a “rubber stamp” — a symbolic authority who could legitimise Company control without challenging it.

- The emperor’s farman (imperial order) provided the legal cover for all British political and fiscal gains in Bengal.

Significance of the Treaty of Allahabad

- It was the first formal political arrangement marking the Company’s transition from a trading corporation to a territorial power.

- It gave the Company complete fiscal control over the richest provinces of the subcontinent.

- It secured Bengal’s surplus revenue, which became the financial base for British expansion in India.

- It enabled the Company to avoid direct governance responsibilities while still exercising complete administrative authority.

- It laid the foundation of the British Indian administrative structure, starting with indirect rule, and would later evolve into full colonial rule.

Significance of the Battle of Buxar (1764)

The Battle of Buxar, fought on 23rd October 1764, was more decisive and historically significant than the earlier Battle of Plassey (1757). It transformed the East India Company from a commercial entity into a full-fledged political power in India.

1. Decisive Victory over Indian Powers

- Unlike Plassey, where only the Nawab of Bengal was defeated, Buxar involved and witnessed the defeat of a triangular alliance:

- Mir Qasim, Nawab of Bengal

- Shuja-ud-Daulah, Nawab of Awadh

- Shah Alam II, the Mughal Emperor

- The defeat of both the Mughal Emperor and the powerful Nawab of Awadh at the hands of the English marked a clear shift in power towards the British.

2. Establishment of British Political Supremacy in India

- The Battle cemented British political dominance in Eastern India, particularly over the rich provinces of Bengal, Bihar, and Orissa.

- This victory marked the beginning of British territorial sovereignty, no longer reliant solely on economic and trading privileges.

- It enabled the East India Company to demand political concessions, ultimately leading to the Treaty of Allahabad (1765), which granted them Diwani rights — the right to collect revenue and administer civil justice.

3. End of Real Mughal Sovereignty

- The Mughal Emperor Shah Alam II was reduced to a pensioner of the Company, a significant symbolic downfall of the Mughal Empire.

- While the British continued to recognize the Mughal Emperor nominally, the real power shifted to Calcutta, not Delhi.

- The battle marked the final eclipse of Mughal authority in practice, although its symbolic presence was maintained until 1857.

4. Transformation of Awadh into a Buffer State

- Though Awadh was restored to Shuja-ud-Daulah, he was now bound by a subordinate alliance with the Company, having to:

- Pay a heavy war indemnity

- Station a British Resident in Lucknow

- Offer military support to the Company on demand

- This created a British-controlled buffer zone between Bengal and the Maratha/Afghan frontier.

5. Confirmation and Expansion of Plassey Gains

- If Plassey gave the British a foothold, Buxar gave them control. It confirmed the gains made at Plassey and extended their political reach:

- Control over the Mughal emperor

- Subjugation of Awadh

- Full control over Bengal’s revenue

- It allowed the unrestricted exploitation of Bengal’s resources, used later to fund British military campaigns in other parts of India.

6. Military Superiority of the British

- The battle exposed the military weakness and lack of unity among Indian rulers.

- Despite the numerical strength of the combined Indian forces, the English emerged victorious due to their:

- Superior military tactics

- Centralized command structure

- Discipline and equipment

- The battle proved that fragmented Indian powers could not withstand a modern, unified European army.

7. Start of Company Rule in India

- The Treaty of Allahabad, following this battle, laid the foundation of Company Raj in India.

- With the Diwani rights, the Company now had access to:

- Administrative control

- Military power

- Revenue generation

- This transformed the East India Company into India’s de facto ruler, especially in the eastern region.

8. Economic Control and Exploitation

- The Company’s revenue rights in Bengal, Bihar, and Orissa gave it control over India’s richest agricultural provinces.

- Bengal’s wealth and resources were now systematically channeled into Company hands, financing:

- The expansion of British military power

- Further conquests across India

- The transformation of a trading company into an imperial force

9. Indirect Rule as a Strategy

- The Company refrained from direct annexation of territories like Awadh or Delhi, preferring to rule indirectly.

- British control now operated through:

- Treaties

- Resident diplomacy

- Subordination of Indian rulers

- This policy of indirect imperialism helped avoid administrative burdens while securing real authority.

Conclusion

The Battle of Buxar was a turning point in Indian history. It marked the beginning of British colonial rule in India, not just as traders but as sovereign rulers. While the Battle of Plassey opened the gates, Buxar locked them behind the British. It established their supremacy in Bengal, placed the Mughal emperor under their influence, and reduced powerful Indian states to mere puppets or buffer allies. It was the real beginning of the Company Raj — one that would, in less than a century, engulf the entire subcontinent.