December 13, 2025 5:55 am

Archaeological Sources are crucial for understanding the history and culture of ancient civilizations. These sources include artifacts, inscriptions, monuments, pottery, coins, tools, and rock art.

Archaeology is the study of our human past through material remains. It provides insight into how ancient people lived, their cultures, and the ways their societies evolved.

What are Material Remains which are the strongest Archaeological Sources?

Material remains include a wide variety of relics, ranging from grand structures like palaces and temples to everyday items such as broken pottery. These remains consist of structures, artifacts, bones, seeds, pollen, seals, coins, sculptures, and inscriptions. Through archaeology, we can recover these items to better understand the lives and cultures of ancient people.

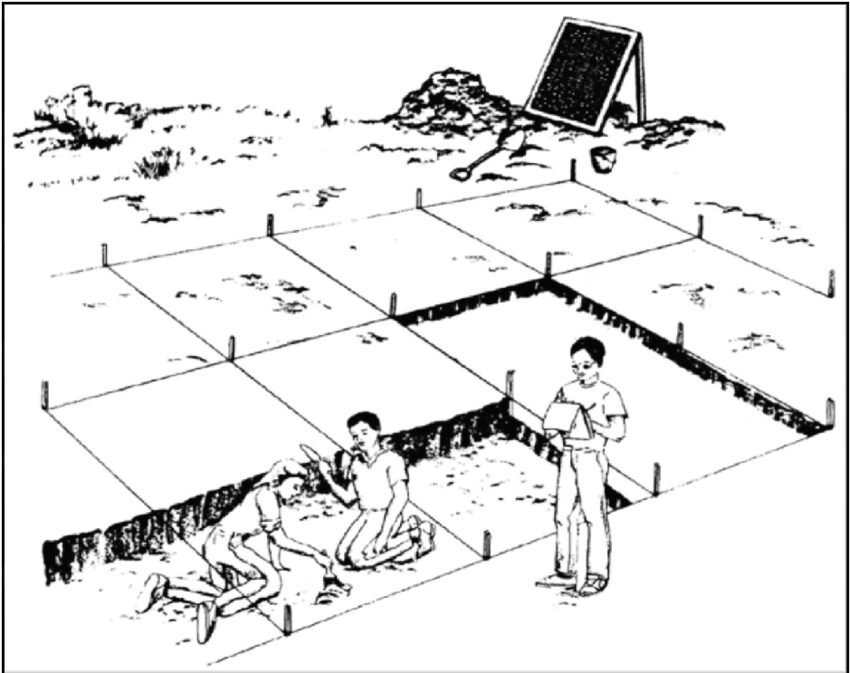

Exploration and Excavation to find Archaeological Sources

Archaeology uses scientific methods to carefully excavate or dig up layers of ancient mounds. These mounds are elevated landforms that cover the remains of old settlements. There are different types of mounds:

- Single-Culture Mounds: These mounds represent only one culture throughout history. For instance, some mounds show evidence only of the Painted Grey Ware (PGW) culture, while others are linked to the Satavahana or Kushan cultures.

- Major-Culture Mounds: These have one dominant culture, but they also contain influences from other cultures.

- Multi-Culture Mounds: These contain evidence of several important cultures existing one after another, or sometimes overlapping.

When archaeologists dig up these mounds, they use two main methods:

- Vertical Excavation: This involves digging straight down to reveal the order in which different cultures lived. It helps to create a chronological sequence of the site’s history.

- Horizontal Excavation: This method involves excavating a large area to get a complete understanding of the culture during a specific time period. However, horizontal excavation is expensive and not as common.

The preservation of ancient remains depends on environmental conditions:

- Dry, Arid Climate: In places like western Uttar Pradesh and Rajasthan, ancient items are often found in a good state of preservation.

- Moist, Humid Climate: In regions like the Gangetic plains, iron objects rust, and mud structures decay, leaving behind mainly stone or burnt brick structures.

Discoveries from Excavations

Excavations have revealed significant insights, such as:

- The establishment of villages around 6000 BC in Baluchistan.

- The development of material culture in the Gangetic plains during the second millennium BC.

- The layout of ancient settlements, including the types of pottery used, the houses people lived in, the cereals they ate, and the tools they used.

- In South India, megalithic graves were discovered, where people buried their dead along with tools, weapons, pottery, and personal items. These graves provide valuable information about life in the Deccan region from the Iron Age onward.

Methods of Dating and Analyzing Remains

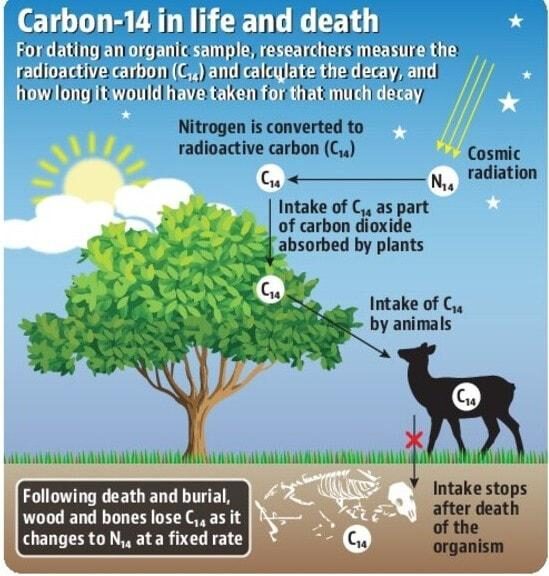

Archaeologists use several methods to determine the age of ancient sites and objects. One of the most important methods is radiocarbon dating. Carbon-14 (C14) is a radioactive form of carbon found in all living things. When an organism dies, the C14 in its body starts to decay at a steady rate. By measuring how much C14 is left, scientists can estimate the object’s age. This method is effective for dating objects up to 70,000 years old.

- Half-Life of C14: The half-life of C14 is 5,568 years, meaning that half of the C14 in an object decays over this period.

- Pollen Analysis: By examining ancient pollen, scientists can understand the climate and vegetation of the past. For example, this method has shown that agriculture was practiced in Rajasthan and Kashmir around 7000–6000 BC.

Scientific Analysis

- Metal Artifacts: Scientists study the components of metal objects to figure out where the metals came from and how ancient people developed their metal technology.

- Animal Bones: Analyzing these bones helps scientists understand whether animals were domesticated and how they were used.

Geological and Biological Studies

- Geological Studies: These studies provide information about the history of rocks and soil, which is important for understanding the environments where ancient people lived.

- Biological Studies: These give insights into ancient plants and animals, showing how humans interacted with their environment. Together, these studies help cover more than 98% of human history.

Ethno-Archaeology

Ethno-archaeology studies modern communities to understand ancient cultures. Many traditional practices in India, such as agriculture, animal husbandry, and craft-making, provide clues about ancient ways of life. For example, the craft of carnelian bead-making in Khambhat, Gujarat, helps researchers understand how beads were made during the Harappan era. Ethno-archaeology also helps fill gaps in our knowledge, such as the role of women in early societies or how hunter-gatherers and shifting cultivators lived. However, it’s important to remember that present-day practices may not always perfectly match ancient ones.

Archaeology as a Source of History

Archaeology gives us a unique perspective on history, especially for the periods before writing was invented, known as prehistory. It is also useful for studying times when writing existed but hasn’t been deciphered yet, called proto-history. Even for periods with written records, archaeology adds valuable information about daily life, technology, and trade. Unlike literary texts, which may focus on elite or royal activities, archaeology provides a more complete picture of everyday life and cultural practices.

The ancient Indians left many material remains, like the stone temples of South India and the brick monasteries of Eastern India. Most of these remains are buried in mounds scattered across the country. Archaeology tells us about the settlements people built, the crops they grew, the tools they made, and the animals they domesticated or hunted. It also gives us a deeper understanding of ancient technology, including the raw materials and techniques used to make various artifacts.

Archaeology helps reconstruct trade routes, networks of exchange, and cultural interactions. It also provides insight into religious practices that texts don’t fully explain. For example, studying ancient temples and religious artifacts can reveal how religion was practiced, which may differ from the descriptions found in sacred texts.

However, there are challenges in using archaeology to write history. An archaeological culture does not always correspond to a specific linguistic group, political entity, or social group like a tribe or clan. One ongoing question is how to explain changes in material culture, such as shifts in pottery styles, which are still not fully understood.

Archaeological evidence does not always give a complete picture. The items found are often things that were lost, thrown away, or left behind when people moved. Not everything survives, especially in tropical regions where heavy rain, acidic soil, and a warm climate make it hard for organic materials to be preserved. Inorganic materials like stone, clay, and metal are more likely to survive. For instance, Stone Age people probably used tools made of wood and bone, but these have mostly decayed, leaving only the stone tools behind.

Epigraphy

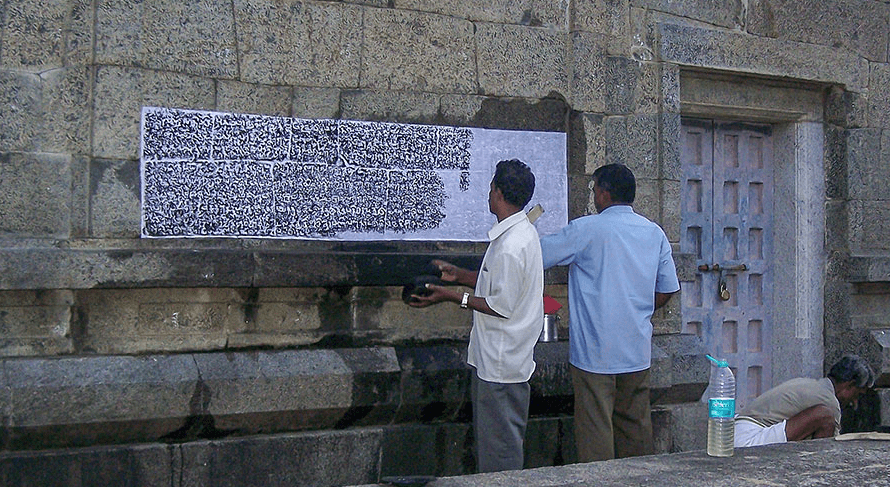

Epigraphy is the study of inscriptions, which are important sources for understanding ancient history. Inscriptions and coins fall under the umbrella of archaeology. The study of the ancient writing used in these inscriptions is called palaeography.

Inscriptions were carved on materials like stone pillars, rocks, copper plates, temple walls, wooden tablets, bricks, or even on images. In ancient India, the earliest inscriptions were often recorded on stone. Later, in the early centuries of the Common Era, people started using copper plates for writing. Even after the use of copper plates became common, many inscriptions in South India continued to be carved on stone, especially on temple walls to serve as permanent records.

Early Inscriptions and Writing Systems

- The Harappan inscriptions, which are yet to be deciphered, were written in a pictographic script that used pictures to represent ideas and objects.

- The oldest deciphered inscriptions are from the late 4th century BCE and are written in Brahmi and Kharoshthi scripts. These include the inscriptions of Ashoka, the Mauryan emperor. Ashoka’s inscriptions were mostly in the Prakrit language and Brahmi script, written from left to right. Some were written in the Kharoshthi script, which goes from right to left.

- In the 14th century AD, Firoz Shah Tughlaq found two of Ashoka’s pillar inscriptions, one in Meerut and another in Topra, Haryana. He brought them to Delhi and asked scholars to decipher them, but they couldn’t. The inscriptions were first deciphered in 1837 by James Prinsep, an official of the East India Company.

Brahmi Script:

The Brahmi script was used across India, except in the northwest. It remained the main script until the end of the Gupta period. In the northwest, Ashokan inscriptions were also written in Greek and Aramaic scripts, especially in parts of Pakistan and Afghanistan. After the 7th century, Brahmi developed into regional scripts, and variations became prominent.

Kharoshthi Script:

- The Kharoshthi script was used primarily in the northwest region, known as Gandhara. Ashoka’s inscriptions at Shahbazgarhi and Mansehra are in this script.

- It continued to be used during the rule of Indo-Greek, Indo-Parthian, and Kushana kings. Kharoshthi was written from right to left and was derived from the Aramaic script. By the 3rd century CE, Kharoshthi had died out.

Brahmi’s Legacy and Development

Brahmi became the parent script for all later South Asian scripts and even influenced scripts in Southeast Asia. It evolved over time:

- Ashokan Brahmi, Kushana Brahmi, and Gupta Brahmi are examples of Brahmi scripts named after dynasties.

- By the late 6th century, Gupta Brahmi developed into the Siddhamatrika or Kutila script, which had sharp angles in the letters.

- Nagari or Devanagari: This script was standardized by around 1000 CE. The proto-Bengali or Gaudi script developed between the 10th and 14th centuries, leading to modern scripts like Bengali, Assamese, Oriya, and Maithili. The Sharada script emerged in Kashmir around the same time.

Scripts in South India

- The earliest Tamil inscriptions were carved in caves around Madurai in the Tamil-Brahmi script, an adaptation of Brahmi for the Tamil language.

- Three major scripts developed: Grantha, Tamil, and Vatteluttu. Grantha was used for Sanskrit, while the other two were for Tamil.

- The modern Telugu and Kannada scripts developed by the 14th–15th centuries, and the Malayalam script came from Grantha around the same time.

Bi-Script Inscriptions

Some inscriptions were written in two scripts, like Brahmi–Kharoshthi. An 8th-century inscription from Pattadakal, of the Chalukya king Kirttivarman II, is written in Sanskrit using both the Siddhamatrika script and the proto-Telugu-Kannada script.

Languages of Inscriptions

- Early Brahmi inscriptions, including Ashoka’s, were written in Prakrit dialects.

- From the 1st to 4th centuries CE, inscriptions used both Sanskrit and Prakrit. The first long Sanskrit inscription is the Junagadh inscription of King Rudradaman in the 1st century BCE.

- By the 3rd century CE, Sanskrit had replaced Prakrit as the main language of inscriptions in northern India. In South India, Sanskrit and Prakrit coexisted, with Sanskrit becoming more dominant in royal inscriptions by the 4th–6th centuries CE.

- Over time, regional languages like Tamil, Kannada, Telugu, Marathi, Oriya, and Hindi emerged in inscriptions.

Classification of Inscriptions

Inscriptions are categorized based on their purpose:

- Official Records: These include royal orders about social, religious, and administrative matters, like Ashoka’s edicts.

- Private Records: Inscriptions made by individuals or guilds, like donations to temples or Buddhist and Jaina establishments.

They are also classified by content:

- Commemorative Inscriptions: Record specific events, like the Lumbini pillar inscription of Ashoka.

- Memorial Stones: Erected in memory of heroes, women who committed sati, or Jaina saints who chose to die through fasting. These are found all over India, with some depicting scenes and inscriptions.

- Donative Inscriptions: Gifts made to religious institutions, recorded on shrine walls or religious images.

Royal Land Grants

Land grants recorded in inscriptions provide information about land ownership and administration. These were often inscribed on copper plates or stone. Examples include grants by the Satavahanas and Kshatrapas at Nashik. The earliest copper plate grants are from the 4th century Pallavas and Shalankayanas.

Prashastis (Eulogies)

Prashastis are inscriptions that praise the achievements of kings. Examples include:

- The Hathigumpha inscription of Kharavela, a 1st-century king of Kalinga.

- The Allahabad Prashasti of Samudragupta, which lists his conquests.

Inscriptions on Waterworks and Charitable Acts

Some inscriptions record public works, like the Junagadh rock inscription of Rudradaman, which describes the construction and repair of the Sudarshana Lake. Others are votive inscriptions marking devotion to gods or donations made for religious purposes.

Inscriptions as a Source of History

Inscriptions are valuable because they are durable and often date back to the events they describe. They offer reliable information about ancient politics, administration, society, and economy. However, they can also be biased, exaggerating the achievements of kings or leaving out defeats. Some inscriptions make contradictory claims, which historians have to cross-check with other sources.

Inscriptions give insights into:

- Political History: They often outline the boundaries of kingdoms and the conquests of kings.

- Administrative Systems: Details of land grants and tax collection provide a picture of governance.

- Social and Economic Life: Inscriptions record land disputes, agricultural practices, and complaints by farmers about taxes, like the inscription of Rajaraja III.

- Religious Practices: They show how different religious sects received patronage, providing information about lost sects like the Ajivikas.

- Art and Architecture: Inscriptions help date structures and sculptures. For example, the Chidambaram temple inscriptions describe dance poses from the Natyashastra.

Numismatics

- Definition: Numismatics is the study of coins, offering essential insights into ancient and medieval history. Coins serve as a vital source of information on economic practices, trade networks, political authority, and cultural developments.

Ancient Indian Currency

- Metal Coins: Ancient Indian currency was made from metals such as copper, silver, gold, and lead. Unlike modern paper currency, these coins were durable and often carried significant historical and cultural value.

- Coin Molds: Coin molds made from burnt clay have been found in large quantities, primarily from the Kushan period. This practice largely disappeared in the post-Gupta period.

- Wealth Storage: In the absence of a formal banking system, people stored wealth in earthenware and brass vessels, which were often hidden as hoards. These hoards were precious reserves used during emergencies or times of need.

- Foreign Influence: Many hoards contain not only Indian coins but also foreign currency, such as coins from the Roman Empire, revealing the extent of ancient trade connections and economic exchanges.

Symbols and Evolution of Coins

- Early Symbols: The earliest Indian coins were simple and featured a few symbols. These symbols included geometric patterns, animals, and plants. As coinage evolved, more intricate designs were introduced, depicting kings, deities, and inscriptions with names and dates.

- Depictions of Authority: Later coins played a significant role in showcasing the power and religious affiliations of rulers. The portrayal of kings on coins often included symbols of divine or royal legitimacy.

- Cultural Significance: The symbols and inscriptions on coins provide valuable cultural and historical information, indicating religious influences, governance systems, and interactions with other cultures.

History of Indian Coinage

- Pre-Coinage Economy:

- In the Stone Age, the concept of currency did not exist, and trade was conducted through a barter system. Goods and services were exchanged directly without a medium of currency.

- The Harappan civilization operated an extensive trade network based on barter. Archaeological evidence from Harappan sites shows an advanced understanding of trade and commerce.

- Mentions in Vedic Texts:

- The Rig Veda refers to terms like nishka (gold ornaments) and hiranya-pinda (gold globules), which were used for wealth storage but were not coins in the modern sense.

- Later Vedic Texts: Words like nishka, suvarna, shatamana, and pada are mentioned, suggesting the use of metal pieces of definite weight for transactions, though they weren’t full-fledged coins.

- Emergence of Coinage:

- The transition to coinage occurred in the 6th–5th centuries BCE, driven by the emergence of states, the growth of urban centers, and the expansion of trade networks.

- Buddhist Texts and Panini’s Ashtadhyayi: References to units like kahapana, karshapana, suvanna, shatamana, vimshatika, and trinshatika indicate the use of coinage.

Punch-Marked Coins

Description and Characteristics: The oldest coins found in India are punch-marked coins, primarily made of silver, with some examples in copper. These coins were often irregular in shape—rectangular, square, or round.

- Manufacture: Blanks for punch-marked coins were cut from metal sheets. Symbols were then hammered onto these blanks using punches. This method allowed for mass production of coins.

- Standard Weight: Most silver punch-marked coins adhered to a standard weight of 32 rattis, or approximately 56 grains, ensuring uniformity.

- Widespread Use: Punch-marked coins were found across the subcontinent and continued to circulate until the early CE period. In peninsular India, they were in use for an even longer duration.

Regional Variations of Punch-Marked Coins

- Taxila Gandhara Type: These coins originated in the northwest region, featuring a heavy weight standard and a single punch mark.

- Kosala Type: Found in the middle Ganga valley, these coins had a heavy weight standard and multiple punch marks.

- Avanti Type: From western India, these coins were characterized by a light weight standard and a single punch mark.

- Magadhan Type: The most common and influential type, originating in Magadha, featured a light weight standard and multiple punch marks. As the Magadhan Empire expanded, this type replaced other regional coin types.

Political Influence on Coinage

- Expansion of the Magadhan Empire: The political dominance of Magadha led to the widespread use of Magadhan punch-marked coins, gradually replacing other local varieties.

- State and Guild Issues: Although punch-marked coins typically lack inscriptions, evidence suggests that most were issued by state authorities. In later periods, coins were also issued by cities and merchant guilds, reflecting the economic and administrative complexity of ancient India.

Uninscribed Cast and Die-Struck Coins

Uninscribed Cast Coins: Shortly after punch-marked coins, uninscribed cast coins made of copper or copper alloys appeared. These coins were created by melting metal and pouring it into clay or metal molds.\

- Geographical Spread: Uninscribed cast coins have been found across most of the Indian subcontinent, except for the far south. They signify an advancement in coin production techniques.

- Molds and Discoveries: Archaeologists have found clay molds at numerous sites, indicating widespread use of this coin-making method. A significant discovery includes a bronze mold at Eran in central India.

- Overlap in Circulation: In several archaeological sites, uninscribed cast coins have been found in the same layers as punch-marked coins. This indicates that both types coexisted for a time, reflecting a transitional phase in Indian numismatics.

- Uninscribed Die-Struck Coins: These coins were predominantly made of copper, with some rare examples in silver.

- Technique: Symbols were struck onto coin blanks using carefully carved metal dies. This method allowed for greater detail and precision compared to cast coins.

- Timeline: The minting of uninscribed die-struck coins likely began around the 4th century BCE and continued to be used extensively in regions like Taxila and Ujjain.

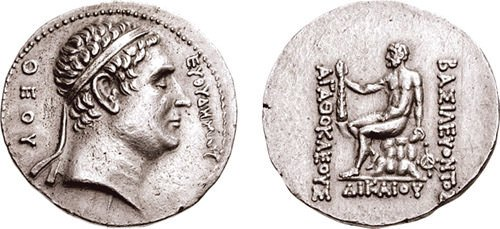

Indo-Greek Influence on Indian Coinage

Introduction of Die-Struck Coins: The Indo-Greeks were instrumental in introducing advanced die-struck coinage techniques to India around the 2nd/1st century BCE. Their coins are known for their high quality and intricate designs.

- Design and Composition: Indo-Greek coins were usually made of silver, though some were also crafted from copper, billon (a silver-copper alloy), nickel, and lead.

- Portraits of Rulers: The obverse of the coins featured realistic portraits of kings, often showing them in various stages of life. For example, coins of Menander and Strato I show the kings aging from young men to elders, indicating long reigns.

- Conjoint Rule: Some coins were issued jointly by kings, reflecting a system of shared or conjoint rule.

- Reverse Designs: The reverse of the coins usually bore religious symbols, representing the spiritual beliefs of the time and emphasizing the rulers’ divine legitimacy.

- Bilingual and Bi-Script Coins:

- Inscriptions: Indo-Greek coins often featured bilingual inscriptions, with the obverse in Greek and the reverse in Prakrit (usually in the Kharoshthi script, though some used Brahmi).

- Cultural Fusion: The use of multiple languages and scripts on these coins reflects the cultural and linguistic diversity of Indo-Greek territories.

Kushana Coinage

Gold and Copper Coins: The Kushanas (1st–4th centuries CE) were the pioneers in issuing large quantities of gold coins in India. They minted coins in gold, copper, and in some cases, bronze. The widespread use of these coins highlights the significance of a growing money economy during their reign.

- Kanishka’s Contributions: One of the most famous Kushana rulers, Kanishka, issued a diverse range of coins that are remarkable for their quality and intricate designs.

- Depiction of Kings and Deities:

- The obverse of Kushana coins typically depicted the king’s figure, along with his name and title. The kings were shown in a variety of poses, such as standing, seated on a throne, or engaged in religious rituals.

- The reverse featured images of deities from various religious traditions, including Brahmanical, Buddhist, Greek, Roman, and other pantheons. This highlights the religious pluralism and cosmopolitanism of the Kushana Empire.

- Legends and Scripts: The legends on Kushana coins were usually in Greek, although some coins also featured Kharoshthi script on the reverse. This reflects the blending of cultures and the influence of Hellenistic traditions.

- Cultural and Religious Symbolism: The inclusion of deities from different religions indicates the Kushana rulers’ inclusive approach to governance and their efforts to legitimize their authority by appealing to a wide range of cultural and religious groups.

Local Coins and Tribal Issues

- Diverse Coinage: The period between the 3rd century BCE and the 4th century CE saw the emergence of numerous coin types issued by tribal chieftains, regional kings, and local authorities. These coins are often referred to as indigenous, tribal, janapada, or local coins.

- Material and Methods: Most of these coins were made from copper or bronze, though there are also examples of coins made from silver and lead. They were either cast or die-struck, showcasing a variety of minting techniques.

- Notable Issuers: Coins from tribes such as the Arjunayanas, Uddehikas, Malavas, and Yaudheyas have been discovered. These coins often display tribal symbols or inscriptions that identify the issuing authority.

- City Coins and Guild Issues: Certain coins bear the names of cities like Ujjayini, Taxila, Kaushambi, and Mahishmati, suggesting that these urban centers had some degree of administrative autonomy. Additionally, some coins were issued by merchant guilds, indicating the economic influence of trade associations.

- Significance of City Coins: Coins marked with the word negama likely represent guild-issued currency, while certain coins from Taxila inscribed with pancha-nekame suggest issuance by a consortium of five merchant guilds.

Satavahana and Ikshvaku Coins

Satavahana Coinage: The Satavahanas issued coins in multiple metals, including copper, silver, lead, and potin (a copper alloy). The coins were generally die-struck, and their legends were inscribed in the Prakrit language using the Brahmi script.

- Unique Features: Satavahana coins sometimes depicted kings, with symbols representing royal authority or the Satavahana dynasty’s association with maritime trade. Some coins also had inscriptions in Dravidian languages.

- Portrait Coins: The Satavahanas issued a small number of portrait coins, mostly in silver or lead, depicting the rulers.

- Post-Satavahana Coinage: In the eastern Deccan, the Ikshvakus (3rd–4th centuries CE) continued the tradition of lead coinage, issuing coins similar in style and fabric to those of the Satavahanas.

- Western Deccan Influence: In the western Deccan, the demand for silver currency increased, driven by the region’s commercial activities. The Kshatrapa ruler Nahapana introduced a silver currency in the Nashik area, which influenced the regional economy.

- Roman Gold Coins: Roman gold coins were also found in large quantities in peninsular India, emphasizing the role of Indo-Roman trade. These coins may have been used as a reserve currency or for large-scale transactions, and some were even locally imitated.

Coins of South Indian Dynasties

- Punch-Marked Coins in the South: Early punch-marked coins discovered in South India were likely dynastic issues, identifiable by specific symbols. For instance, coins from a hoard at Bodinaikkanur near Madurai featured the double carp fish, the emblem of the Pandya dynasty.

- Chola, Chera, and Pandya Coins: Over time, these southern dynasties developed their own coinage systems:

- Chola Coins: Often depicted the tiger, the emblem of the Chola dynasty, and were issued in various denominations.

- Chera Coins: Featured symbols like the bow and arrow. Coins with inscriptions like Valuti have been attributed to the Chera rulers.

- Pandya Coins: Displayed the double fish emblem. Some coins inscribed with the name Makkotai were found near the Krishna riverbed, suggesting Chera-Pandya trade interactions.

Gupta Coinage

Introduction of Gold Dinaras: The Gupta dynasty is renowned for issuing high-quality gold coins, known as dinaras, which marked a significant development in Indian numismatics. These coins were primarily discovered in north India and showcased exceptional craftsmanship.

- Design and Themes:

- The obverse side of Gupta coins typically depicted the reigning king in various poses, emphasizing royal power and martial strength. Common depictions included kings holding a bow, riding a horse, or performing religious rituals.

- Unique Designs: The Gupta king Samudragupta issued a series of coins showing him playing the vina (a stringed musical instrument), highlighting his cultural patronage and artistic interests. Another common design showed kings performing the ashvamedha sacrifice to proclaim their sovereignty.

- Reverse Side: The reverse side often featured religious symbols, such as images of deities, which reflected the religious affiliations and beliefs of the ruling dynasty. These symbols included representations of Lakshmi, Goddess Durga, and Lord Kartikeya.

- Legends and Inscriptions: Gupta coins were inscribed with metrical legends in Sanskrit, a departure from earlier Prakrit inscriptions. The inscriptions often glorified the king’s achievements and divine status.

- Silver and Copper Coinage: In addition to gold dinaras, the Guptas issued silver coins that were influenced by the Kshatrapa coinage in western India. These coins had inscriptions in Brahmi script. Gupta copper coins were rarer and generally less detailed compared to the gold and silver issues.

- Decline in Quality: Towards the later part of Skandagupta’s reign, there was a noticeable decline in the metallic purity of gold coins, indicating economic challenges faced by the empire.

Early Medieval Coinage Debate

- Feudal Order Hypothesis: Historians often debate the state of coinage in the early medieval period. Those who support the idea of a feudal economy argue that there was a decline in coin production, reflecting a decrease in trade and urbanization. They believe that coinage experienced a revival only in the 11th century.

- Counterarguments: However, numismatist John S. Deyell suggests that while the aesthetic quality and diversity of coins may have declined, the overall volume of coins in circulation did not decrease significantly. The economic activity persisted, albeit in a different form.

- Base Metal Coins: Many coins from this period were made of base metal alloys, such as copper and billon. These coins lacked the fine inscriptions and detailed designs of earlier coins, making it difficult to associate them with specific rulers.

- Regional Variations:

- Gurjara-Pratihara Coins: In the Ganga valley, billon coins circulated under the Gurjara-Pratihara dynasty.

- Coins of Rajputana and Gujarat: Various Rajput kingdoms and the Gujarat region also had their own coinage.

- Arab Governors in Sindh: Between the mid-8th to mid-9th centuries, the Arab governors of Sindh minted copper coins, reflecting the Islamic influence in the region.

- Kashmir: In Kashmir, coinage was supplemented by bills of exchange (hundikas) and cowries, reflecting a unique economic system.

Regional Coinage in Bengal and the Deccan

- Bengal Coins: During the 6th–7th centuries, kings like Shashanka issued gold coins in Bengal. However, no coins have been definitively attributed to the Pala and Sena dynasties. References to currency units in their inscriptions are believed to represent theoretical values rather than physical coins.

- Harikela Silver Coins: Harikela coins circulated in Bengal from the 7th to 13th centuries, with local variations issued in different parts of eastern India.

- Western Deccan Coinage: The Chalukyas of Badami are believed to have issued some early medieval coin types. Gold and copper coins attributed to the later eastern Chalukyas reappeared in the 10th century, marking a revival of monetary activity.

- Uncertainty in Attribution: Coins of the Kadambas of Goa (11th–12th centuries) and some gold coins assigned to the Shilaharas of the western Deccan are still subjects of scholarly debate.

Coins of the Far South

- Pallava Coinage: In the far south, the Pallavas issued coins that often depicted lion and bull motifs. Some of these coins had inscriptions with the titles of the ruling monarchs. The Pallava coins played a significant role in the regional economy and showcased their unique artistic style.

- Chola Coins: The Cholas are well known for their coinage, which featured the tiger emblem, a symbol of their dynasty. Chola coins were minted in various denominations and materials, primarily gold, silver, and copper. The obverse side typically displayed the tiger symbol, while the reverse often had inscriptions and other motifs.

- Chola Inscriptions and Emblems: The seals of several Chola copper plate inscriptions depicted the tiger, fish (representing the Pandya emblem), and bow (the Chera emblem). This combination symbolized Chola supremacy over the Pandyas and Cheras. The presence of these symbols on coins emphasized the Chola’s dominance in southern India.

- Unique Discoveries: At Kavilayadavalli in Andhra Pradesh, gold coins featuring the tiger, bow, and other symbols were discovered. These coins had inscriptions like sung, which is believed to be an abbreviation of sungandavirttarulina (meaning “abolisher of tolls”), one of the titles of Kulottunga I. The legends on the reverse may denote mint towns.

- Pandya Coins: The early medieval Pandyas issued copper coins that have been found in significant numbers, especially in Sri Lanka. The Pandya coins commonly displayed the double fish emblem, a symbol of their dynasty’s authority and legacy.

- Chera Coins: The Chera dynasty issued coins featuring symbols like the bow and arrow. Some Chera coins bore legends such as Kollippurai and Kuttuvan Kotai, along with their dynastic emblems. These coins indicate the Cheras’ involvement in regional trade and governance.

Cowries as Currency

- Role of Cowries: Cowries, small marine shells, were used as currency for small transactions in ancient and medieval India. They had a low purchasing power compared to metal coins but were widely circulated.

- Evidence and Usage: In post-Gupta times, cowries became more common, though their use likely started earlier. They were found in large quantities in archaeological excavations.

- At Sohepur in Orissa, 25,000 cowries were discovered alongside 27 Kalachuri coins.

- At Bhaundri village in Lucknow, a hoard of 9,834 cowries was unearthed with 54 Pratihara coins.

- Supplementing Metal Currency: Cowries were used as a substitute for metal coins, especially for small-scale transactions, and in regions where low-denomination coins were scarce. They served as a crucial component of the everyday economy in rural and semi-urban areas.

- Fluctuating Value: The market value of cowries fluctuated based on demand and supply. During periods of scarcity, the exchange rate of cowries for metal coins could increase significantly, reflecting the dynamics of the local economy.

Coins as Historical Sources

- Chronological Arrangements: Coins are valuable for historians because they can be arranged chronologically based on wear and tear. The gradual reduction in coin weight and changes in design allow numismatists to establish timelines for different issues.

- Language and Script: The legends on coins provide information about the evolution of languages and scripts. For instance, the transition from Prakrit to Sanskrit inscriptions on coins reflects broader cultural and administrative shifts.

- Economic Insights: Coins reveal details about ancient economic activities, such as trade networks, craft production, and the role of merchant guilds. Some coins even bear the marks of merchant associations, showing the influence of commerce in society.

- Monetary History: Studying coins sheds light on the monetary policies of different dynasties, including the volume and circulation of coins, the use of precious metals, and fluctuations in monetary value.

- Production and Circulation: The quantity and type of coins minted provide insights into the economic health of ancient states. For example, the extensive distribution of Kushana coins points to a vibrant trade network.

- Economic Prosperity and Decline: The abundance of coins during the post-Maurya and Gupta periods indicates economic prosperity, while the scarcity of coins in the post-Gupta period suggests economic decline. However, as discussed earlier, some scholars debate the extent of this decline.

- Debasement and Economic Stress: Instances of coin debasement, such as those seen during the later Gupta period, are often interpreted as signs of financial crisis. Debasement could result from the state’s need to mint more coins when precious metal supplies were limited or due to an increase in demand for currency.

- Dating Archaeological Layers: Coins found in excavations help date the layers of archaeological sites. For instance, at Sonkh near Mathura, coins were crucial in establishing the site’s chronological sequence.

Coins as a Source of Political History

- Reconstruction of Political Boundaries: Coins are an invaluable resource for reconstructing the political history of ancient India. The area of circulation of a particular dynasty’s coins often helps historians estimate the extent and boundaries of empires. For example, the widespread distribution of Indo-Greek coins provides insights into the territories they controlled, spanning parts of northwest India and beyond.

- Royal Messaging and Dynastic Claims: Coins acted as a medium for broadcasting royal messages. They often featured symbols of power and religious motifs that legitimized the authority of rulers. This is especially evident in the coins of rulers like Samudragupta, whose coins emphasized his conquests and religious piety.

- Genealogies and Succession: Inscriptions on coins sometimes included genealogical details, which have helped historians piece together royal lineages. For instance, the Gupta coins commemorating the marriage of Chandragupta I to a Lichchhavi princess provide evidence of political alliances.

- Challenges in Interpretation: Although coins provide substantial information, they also present interpretative challenges. For instance, the same type of coin could circulate in multiple regions, sometimes beyond the issuing state’s borders. Moreover, coins made of precious metals often had an intrinsic value that allowed them to remain in circulation long after a dynasty’s decline, complicating efforts to date them accurately.

- Multiple Currency Systems: The coexistence of different currency systems in the same region points to a complex economic landscape. In some areas, multiple coin types circulated simultaneously, reflecting overlapping spheres of influence and trade networks.

Biographical Details from Coins

- Personal Details of Rulers: Some coins provide more than just names and titles; they offer glimpses into the lives of kings. For example:

- Chandragupta I’s Marriage: The only known detail about Chandragupta I‘s life comes from coins commemorating his marriage to a Lichchhavi princess.

- Samudragupta’s Ashvamedha: Coins issued by Samudragupta depict the performance of the ashvamedha sacrifice, a symbol of his supreme sovereignty.

- Samudragupta as a Lyrist: The unique lyrist coin of Samudragupta shows him playing the vina, highlighting his patronage of the arts and his multifaceted personality.

- Discoveries and Rulers’ Personalities: The coins of kings like Kumaragupta I similarly emphasize both martial strength and religious devotion, offering a nuanced view of their reigns.

Religious Insights from Coins

- Depiction of Deities: Coins provide valuable information about the religious beliefs of rulers and the broader society. They frequently featured images of deities, which indicate the religious preferences of the issuing monarchs.

- Indo-Greek Influence: The coins of the Indo-Greeks sometimes depicted Indian deities such as Balarama and Krishna, suggesting the integration of local religious traditions.

- Kushana Pantheon: The Kushana kings depicted a wide range of gods from Indian, Iranian, and Graeco-Roman pantheons on their coins. This eclectic mix of religious symbols reflects the cosmopolitan nature of the Kushana Empire and their strategy of appealing to a diverse population.

- Religious Policy and Symbolism: The presence of religious motifs on coins often reflects the state’s religious policy. For example, the Gupta coins featuring Hindu deities like Vishnu and Lakshmi underscore the importance of Brahmanical religion during the Gupta era.

- Legitimization of Power: Coins were used to legitimize political power through religious symbolism. Rulers depicted themselves as divine or semi-divine figures, reinforcing their authority in the eyes of their subjects.

Coins and Art

- Artistic Excellence: Coins from different periods also provide insights into the artistic traditions of the time. The intricate designs on Gupta gold coins, for example, are a testament to the high level of craftsmanship and the aesthetic sensibilities of the period.

- Cultural Fusion: The artistic elements on Indo-Greek and Kushana coins reflect a fusion of Indian and Hellenistic styles, showcasing the cultural exchange facilitated by trade and conquest.

Coins as Indicators of Economic Prosperity

- Economic Health and Trade: The number, variety, and quality of coins issued by a state are often indicators of its economic prosperity. A significant volume of coins points to a flourishing economy, active trade networks, and stable governance. For example:

- Kushana Coins: The widespread circulation of Kushana coins suggests a robust economic system with extensive trade, both domestic and international.

- Gupta Gold Coins: The large number of high-quality gold coins issued during the Gupta period indicates economic prosperity and a thriving money economy.

- Debasement as an Economic Indicator: The debasement of coins, where the metal content is reduced, is typically associated with financial difficulties or a crisis. During the later part of the Gupta Empire, the decline in the purity of gold coins is often interpreted as a sign of economic strain. However, in some cases, debasement could be a practical response to a growing demand for currency, especially if the supply of precious metals was limited.

- Trade and Commerce: Coins reveal the extent and nature of trade in ancient times. For instance, the depiction of a ship on certain Satavahana coins highlights the importance of maritime trade in the Deccan. The presence of Roman coins in South India further underscores the region’s active participation in Indo-Roman trade.

- City Coins and Merchant Guilds: Coins issued by cities and merchant guilds provide insights into the autonomy and economic influence of urban centers and commercial organizations. Guild-issued coins show that commerce and trade had become sophisticated enough to warrant organized currency systems.

- City Administration: Coins marked with the names of cities, such as Ujjayini and Taxila, suggest that these cities had a degree of self-governance and played a significant role in the regional economy.

- Guild Coins: Some coins bear the marks of merchant guilds and were likely issued with the approval of the ruling authorities. This highlights the economic power and organizational strength of trade guilds in ancient India.

Guild-Issued Currency and Economic Organization

- Role of Guilds: In ancient India, merchant guilds were influential economic entities. They facilitated trade, maintained quality standards for goods, and even issued their own coins in some cases. Coins with inscriptions like pancha-nekame from Taxila indicate currency issued jointly by five different guilds, reflecting a well-organized commercial structure.

- Importance of Guilds in Economic Prosperity: The issuance of coins by guilds demonstrates the advanced nature of commerce during this period. It also implies a system where the state and commercial entities worked together to ensure economic stability and growth.

- Trade Networks: The widespread circulation of guild-issued coins points to extensive trade networks that connected different parts of India and even reached international markets. These networks facilitated the exchange of goods, ideas, and culture.

Coins as Sources of Historical Geography

- Mapping Ancient Territories: The geographical spread of coins helps historians identify the political boundaries of ancient states. For example, the circulation of Indo-Greek coins in northwest India provides evidence of their territorial control and trade routes.

- Identification of Ancient Sites: Coins have been instrumental in identifying and dating ancient cities and trade centers. For instance, the discovery of coins at archaeological sites like Kapilvastu and Mathura has helped establish their historical significance.

- Routes of Exchange: The distribution patterns of coins also shed light on the routes of trade and cultural exchange. The presence of Roman coins in South India suggests active trade routes connecting India to the Roman Empire via sea.

Coins and the Evolution of Language and Script

- Linguistic Development: The inscriptions on coins provide crucial information about the evolution of languages and scripts. For example:

- Transition from Prakrit to Sanskrit: Early coins often had inscriptions in Prakrit, but over time, especially during the Gupta period, Sanskrit became the dominant language for inscriptions. This linguistic shift reflects broader cultural and administrative changes.

- Scripts Used: The transition from the Brahmi script to regional scripts can also be traced through coin inscriptions. The use of scripts like Kharoshthi in the northwest, influenced by Indo-Greek and Kushana coins, highlights cultural exchanges and interactions.

Click Below Links to Read and Download as PDF >>

- Indian Feudalism (300-1200 CE)

- Prehistory and Proto-history : A detailed Analysis

- Archaeological Sources: Excavation Epigraphy, Numismatics

- Chanakya’s Arthashastra: A Book on Ancient Indian Statecraft

- Mauryan Empire: Foundation and Expansion

- Megasthenes’ Indika

- Mauryan Art, Architecture, and Sculpture : 4th Century BC Marvels (PDF Download

- Iranian and Macedonian Invasions of India and Their Impact

- Chandragupta Maurya

- Buddhism – An Overview of Ancient Indian Religions

- Jainism : An Overview of Ancient Indian Religions

[…] Archaeological Sources: Excavation Epigraphy, Numismatics […]

[…] Archaeological Sources: Excavation Epigraphy, Numismatics […]

[…] Archaeological Sources: Excavation Epigraphy, Numismatics […]