January 25, 2026 1:54 am

The American Revolution (1765–1783) was a landmark event in history where the Thirteen North American Colonies overthrew British rule, rejected the monarchy, and declared independence, forming the United States of America. The revolution was driven by a combination of political, social, and intellectual transformations, leading the colonists to challenge British authority and demand self-rule.

Background up to 1763

Colonial Exploration and Settlement

During the 16th century, English adventurers began crossing the Atlantic to establish colonies and expand trade. By the 18th century, several European powers, including France, Spain, the Netherlands, and England, had established territories in North America. England, through military victories and strategic policies, became dominant:

- In the 1660s, England seized New Netherlands from the Dutch, renaming it New York.

- By the 18th century, England had driven France out of much of eastern North America and Canada, cementing its territorial supremacy.

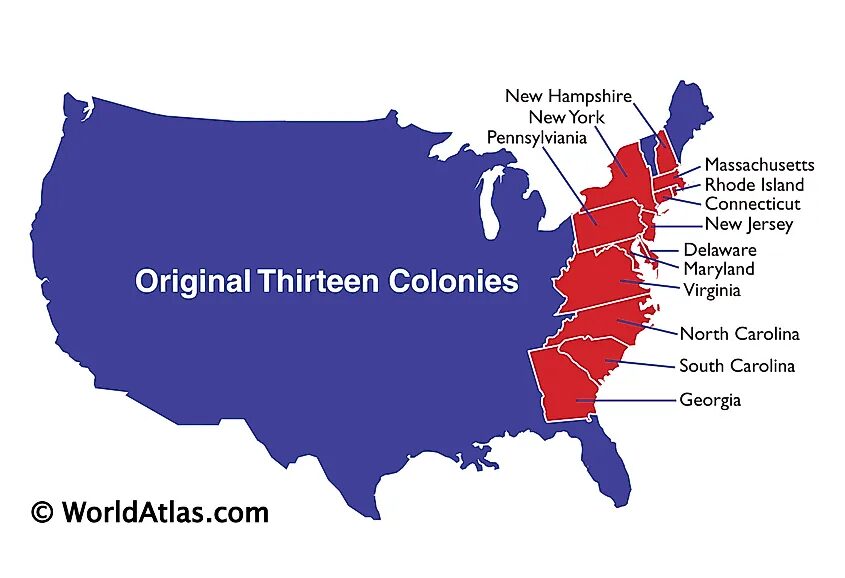

Geography of the American colonies

The geography of the American colonies significantly shaped their economic, social, and political development, creating distinct regional identities across New England, the Middle, and Southern Colonies.

Overview:

The colonies spanned 1,500 miles along the Atlantic coast, benefiting from diverse natural resources, varied climates, and a long coastline that fostered trade.

New England Colonies (Massachusetts, Connecticut, Rhode Island, New Hampshire):

- Geography: Rocky soil, hilly terrain, dense forests, and harsh winters.

- Economy: Subsistence farming, fishing, whaling, and shipbuilding.

- Culture: Tight-knit, religious communities with a strong emphasis on education, reflected in institutions like Harvard University.

Middle Colonies (New York, New Jersey, Pennsylvania, Delaware):

- Geography: Fertile plains, rivers like the Hudson and Delaware, and a moderate climate.

- Economy: Known as the “breadbasket colonies,” they produced grains, traded through ports like New York City and Philadelphia, and developed diverse industries.

- Culture: Ethnically and religiously diverse, with urban centers and a growing middle class.

Southern Colonies (Virginia, Maryland, North Carolina, South Carolina, Georgia):

- Geography: Fertile soil, coastal plains, and a warm, humid climate.

- Economy: Centered on plantation agriculture, growing cash crops like tobacco, rice, and indigo with heavy reliance on enslaved labor.

- Culture: A rigid class system dominated by wealthy planters, rural living, and limited urban development.

Colonial Identity and Interdependence:

- Regional Identities:

- New England emphasized community and education.

- Middle Colonies championed diversity and commerce.

- Southern Colonies relied on agriculture and slavery.

- Trade: Economic interdependence emerged, with New England’s ships transporting Southern cash crops and Middle Colony grains.

- Strategic Geography: Ports and natural boundaries like the Appalachian Mountains shaped commerce and expansion.

Demographics and Society in the Colonies

The American colonies attracted a wide array of settlers:

- Religious Dissenters and Radicals: Many settlers fled religious persecution in Europe, seeking greater freedom.

- Economic Refugees: Paupers, unemployed individuals, and convicts also made the journey to America, driven by desperation and the hope of a better life.

- Spirit of Liberty: Over time, the descendants of these settlers inherited a strong belief in freedom and self-determination.

The colonies offered settlers a level of freedom and opportunity that was unparalleled in Europe. Religious tolerance and communal cooperation fostered a spirit of unity among the diverse populations.

Economic and Social Development

By the mid-18th century, thirteen English colonies spanned the Atlantic coast, each evolving under unique political and economic circumstances:

- Economic Prosperity:

- The colonies had developed infant industries producing goods like wool, flax, and leather.

- The North specialized in fishing and shipbuilding, while the South cultivated large-scale plantations using enslaved African labor to produce cash crops such as tobacco and cotton.

- Trade Relations:

- A vibrant trade network developed between the colonies and Europe, benefiting merchants and fostering economic growth.

- Self-Governance:

- Many colonies gained significant control over their finances.

- Local assemblies in colonies such as Virginia and Pennsylvania began asserting authority, with leaders forming informal committees of governance that operated like cabinets.

- Divergence from England:

- Over time, colonial institutions adapted to the social, economic, and political conditions of the New World. This divergence led to a growing sense of identity separate from Britain.

Political Structures in the Colonies

The colonies operated under different governance systems based on their charters:

- Royal Colonies (e.g., Massachusetts, Virginia):

- These colonies imitated Britain’s “mixed monarchy” structure.

- They had elected assemblies (lower houses), crown-appointed councils (upper houses), and governors representing the King of Britain.

- All laws required approval from the British government but were often enforced with minimal interference.

- Proprietary Colonies (e.g., Pennsylvania, Maryland):

- Governors were appointed by proprietors rather than the crown, offering some level of autonomy.

- Charter Colonies (e.g., Connecticut, Rhode Island):

- These colonies enjoyed the most independence, electing both legislatures and governors. They did not require British approval for laws.

British Policy Before 1763

Mercantilism and Control

The British government adhered to the principles of mercantilism, which viewed colonies as economic extensions of the mother country. Key objectives included:

- Extracting raw materials like sugar and tobacco from the colonies to fuel British industries.

- Restricting colonial trade to benefit British merchants and manufacturers.

- Preventing the establishment of self-governance to ensure dependency on Britain.

Navigation Acts and Trade Restrictions

To enforce mercantilism, a series of Navigation Acts were enacted during the 17th century, including:

- Navigation Act (1651): Required that all goods entering England be transported on British-owned ships.

- Enumerated Commodities Act (1660): Prohibited colonies from exporting goods like sugar, tobacco, and cotton to non-British territories.

- Staple Act (1663): Mandated that all European exports to the colonies pass through British ports.

- Enforcement Act (1696): Allowed customs officials to search and seize goods suspected of violating trade laws.

- Molasses Act (1763): Discouraged the import of French molasses, favoring British sources.

While these laws initially faced lax enforcement, stricter implementation after 1758 fueled colonial resentment.

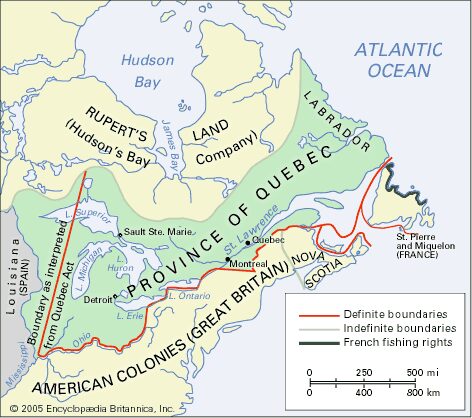

Seven Years’ War and the Treaty of Paris (1763)

The Seven Years’ War (1756–1763) was a global conflict that ended with Britain’s decisive victory over France and Spain, culminating in the Treaty of Paris (1763):

- France ceded its mainland territories in North America, except New Orleans, retaining its Caribbean sugar islands.

- Britain gained all territory east of the Mississippi River, while Spain retained western territories in exchange for Florida.

Consequences of the Seven Years’ War

- Economic Strain on Britain:

- The war left Britain with a massive national debt, prompting the imposition of taxes on the colonies to cover costs.

- Colonial Discontent:

- Colonists felt unfairly burdened by Britain’s financial demands, as they had already contributed soldiers and resources during the war.

- The phrase “no taxation without representation” emerged as a rallying cry against British taxation policies.

- Diminished Need for British Protection:

- With the French threat eliminated, the colonies no longer relied on Britain for protection, increasing their confidence in self-governance.

- Training of Revolutionary Leaders:

- The war provided military experience to future revolutionary leaders like George Washington, William Prescott, and Daniel Morgan.

- French Support for the Revolution:

- Hostilities between Britain and France, exacerbated by the war, encouraged France, Spain, and the Netherlands to support the colonies during the American Revolution.

Crown’s Proclamation of 1763

In an effort to stabilize relations with Native Americans and control westward expansion, Britain issued the Crown’s Proclamation of 1763:

- Provisions:

- Prohibited colonial settlement west of the Appalachian Mountains.

- Reserved lands for Native American tribes to prevent conflicts.

- Colonial Reaction:

- The proclamation was viewed as an intrusion on colonial rights, particularly by settlers eager to expand westward.

- It marked the beginning of direct British intervention in colonial affairs, further aggravating tensions.

Impact on the American Revolution

The Seven Years’ War and subsequent policies profoundly altered the relationship between Britain and its colonies. Britain’s attempts to impose greater control and taxation were met with fierce resistance, as the colonies developed a stronger sense of unity and self-identity. These events set the stage for the American Revolution, a struggle for independence that would reshape the course of history.

Events after 1763

The events following 1763 marked a turning point in the relationship between the American colonies and Great Britain. The imposition of taxes and other restrictive measures by the British government sparked widespread resistance in the colonies, laying the groundwork for the American Revolution. Below is a detailed account of key events and their significance, with critical terms emphasized.

1764–1766: Taxes Imposed and Withdrawn

Currency Act (1764):

- Parliament passed the Currency Act to restrict the use of paper money, which British merchants argued allowed colonists to evade debts.

- It prohibited the colonies from designating paper currency as legal tender for public or private debts.

- While colonists were not barred from issuing paper money, this act caused economic distress in the colonies due to a lack of gold and silver.

Sugar Act (April 5, 1764):

- This act aimed to end smuggling of sugar and molasses from non-British Caribbean sources and to raise revenue for the British Empire after the Seven Years’ War.

- It was essentially a reinvigoration of the Molasses Act of 1733.

- Provisions:

- Customs enforcement was strengthened, and duties on refined sugar and molasses were strictly imposed.

- A Vice-Admiralty Court was established in Nova Scotia to hear smuggling cases without a jury, angering colonists who saw this as an infringement on their rights.

- Colonial Response:

- Colonists protested not against the amount of the tax but against its strict enforcement and lack of representation.

- Benjamin Franklin argued in Parliament that colonists had already heavily contributed to the empire’s defense, making these taxes unjust.

Stamp Act (March 22, 1765):

- The Stamp Act was the first direct tax levied on the colonies, requiring that all official documents, newspapers, pamphlets, and even playing cards bear a tax stamp.

- The act was introduced to raise revenue for the British government to cover the cost of defending and administering the colonies after the Seven Years’ War and Pontiac’s War.

- Colonial Opposition:

- The act was met with widespread opposition, including riots, stamp burnings, and refusal to use stamped paper.

- The colonists argued that taxation without representation violated their rights as Englishmen, and taxation for revenue threatened the foundations of colonial self-government.

- Stamp Act Congress (October 1765):

- Delegates from nine colonies convened in New York to draft a Declaration of Rights and Grievances, asserting that taxes imposed without representation were unconstitutional.

- The Congress rejected the idea of representation in Parliament, citing logistical concerns due to the distance.

- Outcome:

- Facing economic pressure from British merchants affected by colonial boycotts, Parliament repealed the Stamp Act in 1766 but simultaneously passed the Declaratory Act, asserting its right to legislate for the colonies “in all cases whatsoever.”

Virginian Resolution (May 30, 1765):

- The Virginia Assembly passed resolutions rejecting the Stamp Act and asserting that only colonial assemblies had the right to tax the colonies.

Sons of Liberty:

- A secret organization founded in Boston by Samuel Adams and John Hancock to oppose British policies.

- Members of the Sons of Liberty used intimidation, protests, and boycotts to resist the Stamp Act.

- Actions included forcing British agents to resign, destroying stamp supplies, and organizing public demonstrations shouting “Liberty, property, and no stamps!”

- They later played a significant role in events such as the Boston Tea Party (1773).

Quartering Act (May 15, 1765):

- The Quartering Act required colonial authorities to provide food, drink, and accommodations for British soldiers stationed in their towns.

- Colonists saw this as an infringement on their rights and an unnecessary burden.

- Resentment:

- The act was especially unpopular in New York, leading to defiance and contributing to the passage of the Suspending Act as part of the Townshend Acts (1767).

- The act expired in 1770 but left a legacy of mistrust between the colonies and Britain.

Declaratory Act (March 18, 1766):

- Passed alongside the repeal of the Stamp Act, the Declaratory Act affirmed Parliament’s authority to legislate for the colonies “in all cases whatsoever.”

- While colonists largely ignored the Declaratory Act, the repeal of the Stamp Act was celebrated.

Significance of These Events

The period from 1764 to 1766 showcased a critical escalation in colonial resistance against British control. The imposition of taxes such as the Stamp Act and Sugar Act, combined with the Quartering Act, united colonists across different regions in opposition. Key terms such as “No taxation without representation” became rallying cries that solidified colonial identity and laid the groundwork for the American Revolution.

Through events like the Stamp Act Congress and actions of the Sons of Liberty, the colonies began to develop a sense of unity and purpose. This growing sentiment of resistance would culminate in the ultimate quest for independence a decade later.

Events between (1767–1773)

The Townshend Acts (June 1767)

The Townshend Acts were a set of measures passed by the British Parliament in 1767, designed to assert control over the American colonies and generate revenue for Britain. Named after Charles Townshend, the Chancellor of the Exchequer, these laws were viewed by the colonists as a direct threat to their autonomy and ignited widespread resistance.

Key Provisions of the Townshend Acts

- The Suspending Act:

- This act targeted the New York Assembly, prohibiting it from conducting further business until it complied with the Quartering Act (1765), which required colonies to provide accommodations and supplies to British troops.

- The suspension was seen as a direct assault on colonial self-governance and set a precedent for punitive actions against dissenting assemblies.

- The Revenue Act:

- Imposed import duties on goods like lead, glass, paper, paint, and tea upon their arrival in colonial ports.

- Unlike earlier trade regulations, this act was designed to raise revenue for the British treasury, furthering colonial grievances about taxation without representation.

- The Commissioner of Customs Act:

- Established a centralized Board of Customs Commissioners in Boston to oversee the collection of duties.

- Included additional measures such as search warrants, writs of assistance, and a network of officers and coast guard vessels to combat smuggling.

- These intrusive measures were seen as arbitrary and oppressive, sparking widespread defiance.

- The Indemnity Act:

- Lowered duties on tea imported to Britain by the East India Company and refunded 25% of the tax on tea re-exported to the colonies.

- Aimed to help the East India Company compete with Dutch smugglers, it incentivized colonists to purchase British tea, further entangling the colonies in Britain’s economic strategy.

- The Vice Admiralty Court Act (1768):

- Created new courts in America to prosecute smuggling cases without the use of local juries.

- Granted Royal courts jurisdiction over customs violations, bypassing colonial courts, and intensifying resentment toward British authority.

Colonial Resistance to the Townshend Acts

The acts struck at the heart of colonial traditions of self-governance and were met with strong opposition:

- Political Protests:

- John Dickinson wrote his influential pamphlet, Letters from a Farmer in Pennsylvania, arguing that Parliament had no right to tax the colonies to raise revenue, declaring the acts unconstitutional.

- The Massachusetts Circular Letter, drafted by Samuel Adams in February 1768, condemned the Townshend Acts as an infringement of the colonies’ natural and constitutional rights.

- This letter was endorsed by assemblies in Maryland, Virginia, South Carolina, and Georgia, despite orders from the King to dissolve any assembly that supported it.

- Economic Boycotts:

- Merchants and colonists organized widespread non-importation agreements, refusing to purchase British goods to apply economic pressure on British manufacturers.

- In Boston, an agreement was signed to boycott specific British goods, including those taxed under the Townshend Acts.

- Direct Actions:

- Customs officials were harassed, smuggled goods were circulated openly, and violent acts of defiance occurred.

- British Military Presence:

- In response to mounting unrest, British troops were deployed to Boston in October 1768 to support the Board of Customs Commissioners. This heightened tensions, culminating in events like the Boston Massacre.

The Boston Massacre (March 5, 1770)

The arrival of British troops in Boston in 1768 created a volatile situation. The military presence was seen as a provocation by the colonists.

- The Incident:

- A crowd of colonists began taunting and throwing objects at a group of British soldiers stationed outside the Customs House.

- Tensions escalated, and one soldier discharged his musket after being struck by a snowball. Other soldiers opened fire, killing five civilians.

- The event was immediately labeled the Boston Massacre by Samuel Adams, who used it as propaganda to unite the colonies against British oppression.

- Aftermath:

- The soldiers involved were tried but received light sentences, further inflaming colonial anger.

- The Boston Massacre became a pivotal moment in colonial resistance, symbolizing British tyranny and solidifying support for independence.

Repeal of the Townshend Acts (April 12, 1770)

Under Lord North’s leadership, Parliament repealed most of the Townshend duties in 1770, except the tax on tea, as a symbolic assertion of British authority.

- Impact on Colonies:

- The repeal temporarily reduced tensions, leading to a cessation of the non-importation movement.

- However, the retention of the tea tax kept radical patriots, such as Samuel Adams, active in their efforts to maintain opposition to British rule.

The Committees of Correspondence (1772)

With tensions persisting, Samuel Adams initiated the formation of Committees of Correspondence in Boston in 1772 to coordinate colonial resistance.

- Purpose:

- To establish a network of communication among colonies, warning of British actions and planning resistance.

- To provide leadership and foster unity in the growing independence movement.

- Expansion:

- Virginia, the largest colony, formed a permanent committee in early 1773, with prominent members like Patrick Henry and Thomas Jefferson.

- By 1774, all colonies except Pennsylvania and North Carolina had established similar committees.

- Legacy:

- These committees became the foundation of revolutionary leadership, organizing resistance efforts and managing the war effort at local levels.

The Burning of the Gaspee (June 10, 1772)

The HMS Gaspee, a British customs ship, ran aground near Warwick, Rhode Island, while pursuing a suspected smuggler. This event became a symbol of colonial defiance:

- The Attack:

- Members of the Sons of Liberty, angered by the Gaspee’s aggressive enforcement of British trade laws, attacked the ship.

- The raiders boarded the vessel, wounded its captain, and set it ablaze.

- British Response:

- The British government was outraged and formed a special commission to investigate the incident.

- The commission threatened to send the culprits to England for trial, bypassing colonial judicial systems, which sparked alarm and protests across the colonies.

- Colonial Reaction:

- The Committees of Correspondence, led by figures like Samuel Adams, used the incident to warn other colonies of British overreach.

- The lack of evidence and refusal of colonists to cooperate rendered the commission ineffective, further emboldening colonial defiance.

Publication of Thomas Hutchinson Letters (July 1773)

The publication of Governor Thomas Hutchinson’s letters revealed his support for restricting colonial liberties, intensifying distrust of British intentions.

- The Content:

- In his correspondence, Hutchinson argued for a “greater restraint of natural liberty,” advocating for stricter control over the colonies.

- The letters were used as evidence of a systematic British plot to suppress American freedoms.

- The Fallout:

- Benjamin Franklin, then the colonies’ postmaster general, admitted to leaking the letters, leading to his dismissal from his position.

- Hutchinson’s reputation was irreparably damaged, and the Massachusetts Assembly petitioned for his recall.

This episode heightened colonial suspicions of British motives, further aligning public sentiment against the Crown.

The Tea Act (May 10, 1773)

The Tea Act of 1773 aimed to rescue the financially struggling British East India Company and reinforce British authority over the colonies. However, it reignited colonial resistance and set the stage for the Boston Tea Party.

Provisions of the Tea Act:

- East India Company Monopoly:

- The Act granted the East India Company exclusive rights to export tea directly to the colonies, bypassing colonial merchants.

- Reduced Prices:

- By eliminating intermediary costs, the Act allowed the company to sell tea at lower prices than colonial and Dutch smugglers.

- Retention of the Tea Tax:

- The Act retained the 3 pence per pound tax on tea from the Townshend Acts, symbolizing Britain’s right to tax the colonies.

- Shipping Reforms:

- Tea could be shipped directly from China to the colonies, further undercutting colonial merchants.

British Expectations:

The British government, led by Lord North, anticipated colonial approval of the cheaper tea. However, the Act instead provoked widespread outrage.

Colonial Reaction to the Tea Act:

- Economic Concerns:

- Colonial Merchants: Merchants who previously acted as intermediaries for tea imports were cut out of the trade, threatening their livelihoods.

- Smugglers: The Act undercut the profits of those involved in the illegal Dutch tea trade.

- Shopkeepers: Only those approved by the East India Company could sell tea, further centralizing control.

- Political Grievances:

- Colonists viewed the Act as a Trojan horse, using cheaper tea to coerce them into accepting taxation without representation.

- Memories of earlier disputes, such as the Stamp Act, resurfaced, stoking resentment.

- Public Mobilization:

- Sons of Liberty: This group organized public demonstrations and intensified their propaganda efforts.

- Boycotts: Colonists renewed their commitment to non-importation agreements, vowing to avoid British tea altogether.

- Press Campaigns: Newspapers and handbills spread anti-British sentiment, rallying opposition to the Act.

- Resolutions and Protests:

- Public meetings across major cities like Philadelphia and New York condemned the Act.

- In Philadelphia, a resolution declared that anyone aiding in the unloading or sale of tea was an “enemy to his country.”

The Tea Act in Action:

When ships laden with tea reached American ports, colonial resistance intensified:

- In New York and Philadelphia, the ships were turned away and forced to return to England.

- In Charleston, the tea was offloaded but left to rot in storage.

- In Boston, the situation escalated into a direct confrontation.

The Boston Tea Party (December 16, 1773)

The Boston Tea Party was a dramatic act of protest against the Tea Act and British taxation policies.

The Incident:

- Planning the Protest:

- The Sons of Liberty, led by Samuel Adams, John Hancock, and Paul Revere, organized the event.

- To conceal their identities, the participants disguised themselves as Mohawk Indians.

- The Protest:

- On the night of December 16, over 180 patriots boarded three British ships—Dartmouth, Eleanor, and Beaver—anchored in Boston Harbor.

- They destroyed 342 chests of tea, valued at approximately £10,000, by dumping them into the harbor.

Colonial and British Reactions:

- Colonial Response:

- The event was celebrated by many as a bold act of defiance.

- The Sons of Liberty gained widespread support, while moderates grew increasingly critical of British policies.

- British Retaliation:

- The Crown viewed the Boston Tea Party as an act of treason and responded with the Intolerable Acts (1774).

Effects and Significance of the Boston Tea Party

- Immediate Repercussions:

- The Royal Navy blockaded Boston Harbor, crippling the colony’s economy.

- British troops were deployed to enforce the blockade and suppress dissent.

- The Intolerable Acts:

- A series of punitive measures, including the Boston Port Act, Massachusetts Government Act, and Quartering Act, were implemented to punish Massachusetts.

- Colonial Unity:

- The harsh British response galvanized other colonies, leading to the formation of the First Continental Congress in 1774 to coordinate resistance.

- Momentum for Revolution:

- The Boston Tea Party symbolized the growing determination of the colonies to resist British control.

- It marked a point of no return, setting the colonies on the path to war.

Broader Implications of 1772–1773

The events of this period underscore the deepening rift between Britain and its American colonies. Key themes include:

- Resistance to British Authority: The colonies increasingly viewed British actions as violations of their rights and freedoms.

- Rise of Revolutionary Leadership: Figures like Samuel Adams, Benjamin Franklin, and Thomas Jefferson emerged as influential voices for independence.

- Unified Action: The Committees of Correspondence and events like the Boston Tea Party fostered a sense of shared purpose among the colonies.

These developments laid the groundwork for the American Revolution, transforming isolated acts of defiance into a coordinated movement for independence.

Significance of the Period (1767–1773)

The measures taken during this period—particularly the Townshend Acts and Tea Act—played a critical role in unifying the colonies against Britain. Key developments included:

- The emergence of organized resistance through groups like the Committees of Correspondence.

- Heightened tensions due to incidents like the Boston Massacre.

- Economic and political measures, such as boycotts and circular letters, which fostered cooperation among colonies.

These events further polarized colonial society, with radicals pushing for independence while conservatives sought reconciliation. Ultimately, the period set the stage for the American Revolution, with increasing defiance culminating in the events of 1775.

The Intolerable Acts, First Continental Congress, and the Road to War (1774–1775)

The years 1774–1775 were pivotal in escalating the conflict between the American colonies and the British Crown, leading directly to the outbreak of the Revolutionary War. The Intolerable Acts and the First Continental Congress were central to this escalation, as they unified colonial opposition to British policies and set the stage for armed resistance.

The Intolerable Acts / Coercive Acts (1774)

The Intolerable Acts, also known as the Coercive Acts, were a series of punitive laws passed by the British Parliament in response to the Boston Tea Party. These acts were designed to restore order in Massachusetts but instead inflamed colonial opposition, leading to greater unity among the colonies.

The Five Intolerable Acts

- The Massachusetts Government Act:

- Altered the Massachusetts Royal Charter, significantly reducing self-governance.

- Members of the council were to be appointed by the Crown, stripping local assemblies of their authority.

- Town meetings were forbidden without prior approval from the governor, undermining the colony’s ability to organize resistance.

- The Administration of Justice Act:

- Allowed British soldiers accused of crimes to be tried in England or another colony, effectively granting them immunity from local justice.

- This act was seen as an affront to colonial judicial authority and an attempt to protect British troops from accountability.

- The Boston Port Act:

- Closed the Port of Boston until the colonists compensated the British for the tea destroyed during the Boston Tea Party.

- The blockade crippled Boston’s economy, creating widespread hardship and resentment.

- The Quartering Act:

- Resumed the practice of quartering British troops in private homes without the owner’s consent.

- This act symbolized the Crown’s disregard for colonial rights and personal property.

- The Quebec Act:

- Extended the boundaries of Quebec southward to the Ohio River, encroaching on lands claimed by several American colonies.

- Granted religious freedom to Catholic Canadians, allowing them to hold public office.

- Viewed as a direct threat to Protestant dominance and territorial ambitions in British America, it alienated colonists and deepened their distrust of British intentions.

Colonial Response to the Intolerable Acts:

- The acts were perceived as a coordinated assault on colonial liberties.

- Many colonists viewed them as a blueprint for authoritarian rule that could eventually be imposed on all colonies.

- The Committees of Correspondence disseminated information about the acts, uniting the colonies in opposition.

The First Continental Congress (September 1774)

The First Continental Congress convened in Philadelphia on September 5, 1774, as a direct response to the Intolerable Acts. It marked the first significant effort to coordinate resistance across all thirteen colonies.

Key Participants and Objectives:

- Delegates included prominent leaders such as Patrick Henry, George Washington, John Adams, Samuel Adams, and John Dickinson.

- The Congress sought to address colonial grievances and present a united front against British oppression.

Major Actions of the First Continental Congress:

- Declaration of Rights and Grievances:

- Affirmed the colonists’ rights to life, liberty, property, and trial by jury.

- Denounced taxation without representation and the stationing of British troops in the colonies without consent.

- Petition to the King:

- Appealed to King George III to repeal the Intolerable Acts and restore colonial rights.

- The petition expressed loyalty to the Crown but criticized Parliament’s overreach.

- The Articles of Continental Association (October 20, 1774):

- Called for a boycott of British goods, including imports, exports, and consumption.

- Established citizen committees to enforce the boycott and ensure compliance.

- Rejection of Galloway’s Plan:

- Joseph Galloway, a delegate from Pennsylvania, proposed a plan for reconciliation, which included the creation of an American legislature under British oversight.

- The plan was narrowly rejected, reflecting the growing divide between moderate and radical factions.

Significance of the Congress:

- The First Continental Congress fostered a sense of unity among the colonies and demonstrated their ability to act collectively.

- It laid the groundwork for future collaboration, leading to the Second Continental Congress and the eventual declaration of independence.

The Articles of Continental Association (October 1774)

The Articles of Continental Association, adopted on October 20, 1774, were a key outcome of the First Continental Congress.

Provisions of the Articles:

- Enforced a universal prohibition of trade with Great Britain.

- Prohibited the importation, exportation, and consumption of British goods.

- Established local committees to oversee compliance and mobilize public support.

Impact of the Articles:

- The boycott exerted significant economic pressure on British merchants and manufacturers, amplifying colonial demands for reform.

- The committees became de facto governments in many regions, further eroding British authority.

Patrick Henry’s “Give Me Liberty or Give Me Death” Speech (March 23, 1775)

Delivered at the Virginia Convention in St. John’s Church, Richmond, Patrick Henry’s fiery speech galvanized support for the revolutionary cause.

Key Themes and Impact:

- Henry emphasized the urgency of resistance, declaring that liberty was worth the ultimate sacrifice: “Give me liberty, or give me death!”

- His speech convinced the convention to prepare Virginian troops for the impending conflict.

- It marked a turning point in rallying public opinion toward armed resistance.

The Road to Revolution (1774–1775)

The measures enacted by the British government and the colonial response during this period set the stage for open conflict.

Rising Tensions:

- British efforts to enforce the Intolerable Acts deepened colonial resentment and fueled demands for independence.

- The establishment of colonial militias and preparations for war demonstrated the growing determination to resist British rule.

Significance of the Period:

- The events of 1774–1775 highlighted the collapse of reconciliation efforts and the inevitability of war.

- The ideological foundation of the Revolution, emphasizing natural rights and representative government, became firmly entrenched in the colonial mindset.

This pivotal period ultimately led to the Battles of Lexington and Concord (April 1775), marking the beginning of the American Revolutionary War.

[…] American Revolution was a watershed moment in global history. It marked the first successful rebellion of a colony […]