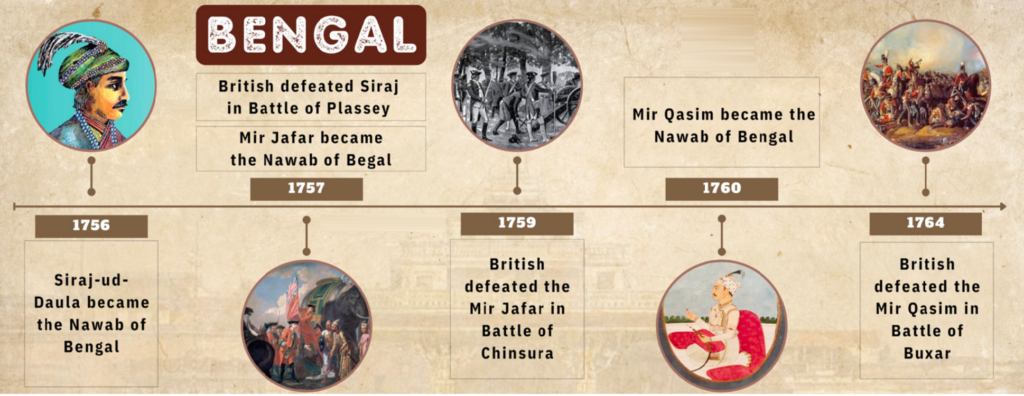

January 25, 2026 5:49 am

Background of Bengal: Rise of Autonomy Under Murshid Quli Khan

Bengal’s Shift Away from Mughal Control

After 1717, Bengal started functioning more independently of the Mughal Empire. This shift began when Murshid Quli Khan became the governor (Subahdar) of Bengal. Unlike earlier times, he was allowed to hold both the posts of nazim (governor) and diwan (revenue officer). This was unusual and broke the traditional Mughal system of dividing power between two officers to prevent misuse or over-centralization.

Administrative Power and Revenue Control

With control over both administration and revenue, Murshid Quli Khan was able to centralize authority. While he did not officially break ties with the Mughal Empire, he started running Bengal as an almost independent province. He continued to send regular revenue to the Mughal court, which was financially struggling at the time. In fact, Bengal’s revenue was often the only reliable income for the empire.

Murshid Quli Khan’s Revenue Reforms

Murshid Quli Khan’s strength came from his strong revenue system. He brought major reforms that ensured Bengal remained a surplus-paying region even when the rest of the empire was facing instability.

- Between 1700 and 1722, Bengal’s total revenue collection increased by 20%.

- He conducted detailed land surveys and forced zamindars (landowners) to pay revenue fully and on time.

- He promoted a few large and efficient zamindaris and removed inefficient or disobedient zamindars. Their lands were taken over as khalisa (royal land).

By the time he died in 1727, the 15 biggest zamindars in Bengal were contributing half of the province’s total revenue.

Rise of New Power Groups: Zamindars and Bankers

Alongside zamindars, a new group of rich merchants and bankers also became powerful. These urban elites became important players in Bengal’s politics and economy. Their increasing wealth gave them more influence, and they began playing key roles in trade and state finance

Trade and Political Economy of Bengal (17th–18th Century)

Commercial Prosperity During Murshid Quli Khan’s Rule

Bengal was known for its lucrative trade, even before the rise of British power. During the rule of Murshid Quli Khan, Bengal’s economic position grew stronger due to political stability and increased agricultural output. This created a solid foundation for internal and overseas trade.

- Major Exports: Bengal exported silk, cotton textiles, sugar, oil, and clarified butter.

- Trade Routes:

- Overland: Goods were sent through northern and western Indian trade centers to Persia and Afghanistan.

- Maritime: Through Hughli port, goods reached Southeast Asia, the Persian Gulf, and the Red Sea.

Shift to Maritime Trade in the 18th Century

As political instability grew across north India in the early 18th century, overland trade declined partially, but oceanic trade flourished. European companies—Dutch, French, and English—began to increase their investment in Bengal.

- By the first half of the 18th century, Europe became the main destination for Bengal’s goods.

- This led to significant expansion in the textile industry, especially for European markets.

Bullion Inflow and Economic Integration

Bengal had a favourable balance of trade. European companies brought in large amounts of silver (bullion) to buy Bengal’s products.

- This silver was easily absorbed into Bengal’s cash economy and used for revenue payments to Delhi.

- Bengal’s economy became more liquid and monetised, supporting both trade and administration.

Role of Merchants, Bankers, and Zamindars

Merchant Community and Trade Dominance

Trade in Bengal was led by Hindu, Muslim, and Armenian merchants. Many of them were wealthy and influential.

- Notable Merchants:

- Umi Chand – a Hindu merchant with large influence.

- Khoja Wajid – an Armenian merchant who owned a fleet of ships.

- They had cordial ties with the administration, and the state did not interfere harshly with merchant affairs.

Bankers and State Revenue

As zamindars were under pressure to pay revenue regularly, bankers and financiers became crucial to Bengal’s economy.

- They provided credit, security, and loans at every step of the revenue process.

- In return, they got patronage from the nawabs, which increased their influence in the administration.

Rise of Jagat Seth Banking Family

- The Jagat Seths emerged as the most powerful banking house in Bengal.

- In 1730, they became the treasurers of Bengal and gained control over the mint.

- Their political support later played a major role in the transfer of power from Sarfaraz Khan to Alivardi Khan.

New Power Structure in Bengal

By the mid-18th century, Bengal’s governance became cooperative in nature, dominated by three key groups:

| Group | Role |

|---|---|

| Zamindars | Collected land revenue and maintained local influence |

| Merchants | Controlled trade and shipping; maintained strong ties with foreign traders |

| Bankers | Financed state functions, provided liquidity, and handled treasury |

Together, these groups held real power. The nazim (provincial governor) now had to depend on their support. This limited the autonomy of the nawab himself and created a fragile balance of power.

The 1739–40 Coup and Rise of Alivardi Khan

In 1739–40, a significant shift occurred when Sarfaraz Khan, who had inherited the position of nazim from his father Shuja-ud-Din, was overthrown.

- Why the Coup Happened:

- Sarfaraz was seen as inefficient.

- He antagonised the Jagat Seths and lost support of key zamindars and officers.

- With support from the Jagat Seth family and military commanders, Alivardi Khan staged a coup and became the new Nawab of Bengal.

- He later received formal approval from the Mughal emperor, though Bengal was now functioning independently.

Alivardi Khan’s Rule and De Facto Independence

Alivardi Khan’s rule (1740–1756) marked a clear break from Mughal control:

- All major appointments were now made without referring to the Mughal emperor.

- Revenue payments to Delhi stopped.

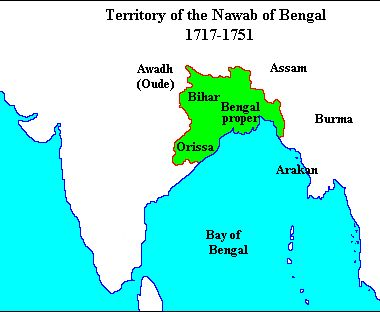

- Although no formal declaration of independence was made, Bengal, along with Bihar and Orissa, was now fully autonomous in practice.

Alivardi Khan’s Relations with European Companies

Alivardi maintained a careful and calculated policy toward European trading companies:

- During the Maratha invasions, he allowed them to build fortifications, such as the Maratha Ditch around Calcutta in 1742 (a 3-mile long moat dug by the British for defense).

- However, he also collected large sums of money from these companies to finance his wars.

- He remained aware of European rivalries in the south (especially British–French conflicts), and tried to prevent such conflict from entering Bengal.

Succession Crisis and Decline of Stability

In 1756, Alivardi Khan died and named his 23-year-old grandson, Siraj-ud-Daulah, as his successor.

- His succession was challenged by:

- Shaukat Jung, Faujdar of Purnea

- Ghaseti Begum, Alivardi’s daughter

- This led to factionalism within the court. The powerful zamindars and merchant groups felt threatened by Siraj’s strong-willed and ambitious nature.

British Intervention: The Conspiracy and the Battle of Plassey 1757

As internal tension increased:

- The English East India Company found an opportunity to interfere in Bengal’s politics.

- The Plassey Conspiracy of 1757 involved several discontented nobles and financiers—including Mir Jafar, Jagat Seths, and others—joining hands with the British to remove Siraj-ud-Daulah.

- This led to the Battle of Plassey, where Siraj was defeated and killed, ending the autonomous Nawabi rule in Bengal.

The Conflict Between the English and the Nawabs of Bengal: Siraj and the English

By the early 18th century, the British East India Company had established a strong presence in India through its three main presidencies: Fort St. George in Madras, Fort William in Calcutta, and Bombay Castle in western India. These were independent administrative units governed by a President and a Council appointed by the Court of Directors in London. To expand influence, the British adopted a strategy of forging alliances with Indian rulers, offering them military protection in return for trade privileges and internal concessions. Many Nawabs, faced with threats from rebels or rival claimants, agreed to such arrangements.

By this period, the Company had overcome its commercial competition with the Dutch and Portuguese. The only serious European rival remaining in India was the French East India Company, which had two significant centres of power: Chandernagar in Bengal and Pondicherry on the Carnatic coast. Both were governed under the presidency of Pondicherry.

Bengal’s Rising Commercial Importance

The conflict between the Nawabs of Bengal and the British developed primarily because of Bengal’s growing centrality to the Company’s trade. As the 18th century progressed, Bengal began replacing western Indian centres like Bombay, Surat, and Malabar in importance. By this time, goods from Bengal—especially textiles—accounted for nearly 60% of all British imports from Asia. Bengal had become the commercial backbone of the Company’s operations in the East.

In 1690, Mughal Emperor Aurangzeb granted the British Company the right to carry on duty-free trade in Bengal in return for a fixed annual payment of Rs. 3,000. Soon after, Calcutta was founded, and by 1696, its fortification had begun. In 1698, the Company was granted zamindari rights over three villages: Kolikata, Suranuri, and Gobindapur. These laid the foundation for British political and commercial control in the region.

Though this arrangement was temporarily disrupted after Aurangzeb’s death, it was formalised again through a farman issued by Emperor Farrukhsiyar in 1717, which reinforced the earlier privileges and added new ones. For the same nominal sum of Rs. 3,000 per year, the Company was allowed:

- To carry on duty-free trade in Bengal,

- To rent thirty-eight villages around Calcutta,

- To use the royal mint for coining currency.

It is commonly believed that these concessions were influenced by William Hamilton, a Company surgeon who treated Farrukhsiyar for a serious illness. In gratitude, the Emperor granted far-reaching trade privileges to the Company.

Initial Resistance by Murshid Quli Khan

The 1717 farman soon became a point of friction between the British and the then-governor of Bengal, Murshid Quli Khan, who had become increasingly autonomous in administering the province. He objected to the misuse of the duty-free provision, especially in the context of private trade by Company officials, which was not covered by the original farman.

To circumvent restrictions, the Company began issuing dastaks (passes) to Indian merchants, allowing them to evade local customs duties. At the same time, the Company imposed high duties on goods entering their areas from Bengal, severely affecting the Nawab’s revenue. Murshid Quli Khan objected to this dual policy and refused to extend the farman’s privileges to cover private trade.

He also refused to allow the purchase of the thirty-eight villages and denied the Company permission to mint coins. These early refusals set the stage for a long-term conflict that began in 1717 and steadily intensified over the decades.

French Threat and Escalation of Tensions

In 1740, the War of Austrian Succession in Europe brought the Anglo-French rivalry into Indian politics. This introduced a new element into the British relationship with the Nawabs. The then Nawab of Bengal, Alivardi Khan, maintained strict neutrality and forbade both the British and French from engaging in open hostilities within Bengal. However, the French victories in southern India made the British deeply suspicious of the Nawab’s capacity to protect their interests.

Meanwhile, in the 1750s, British private trade suffered serious losses due to French competition, often aided by Indian merchants. This pushed the Company to strengthen its defences in Bengal, without the Nawab’s permission. In 1755, the British began renovating the fortifications at Calcutta, openly defying the Nawab’s authority. At the same time, they gave shelter to fugitives from the Nawab’s administration, directly undermining his control.

Siraj-ud-Daulah and Breakdown of Relations

In 1756, after the death of Alivardi Khan, his 23-year-old grandson Siraj-ud-Daulah ascended the throne of Bengal. Siraj’s accession was not smooth and was challenged by internal rivals like Shaukat Jung and Ghaseti Begum, leading to an unstable political climate. Siraj, described by some contemporary observers as having a volatile temperament and poor judgment, was also deeply suspicious of the European companies. He was particularly concerned about the wealth, influence, and defiance shown by the British in Bengal.

Siraj viewed the misuse of dastaks and the fortification of British settlements as direct attacks on his sovereignty. Two immediate causes led to an open confrontation:

- The British had granted asylum to Krishna Ballabh, an official accused of fraud by the Nawab.

- The new fortifications being built at Calcutta without prior permission.

These developments, coupled with the Nawab’s perception that the Company was undermining his authority, led to a complete breakdown of relations.

Attack on Kasimbazar and the Capture of Calcutta

Siraj sent warnings to the Company to stop its unauthorized activities. When they were ignored, he acted swiftly. He attacked and seized the British factory at Kasimbazar, an important trading post. The Governor of Calcutta, Roger Drake, responded by preparing for military confrontation instead of negotiating. This provoked Siraj further, who then attacked Calcutta, capturing it on 20 June 1756.

During the assault, most British officials, including Drake, escaped. However, 146 soldiers and civilians were left behind, led by John Zephaniah Holwell, a senior Company officer and former military surgeon.

The Black Hole of Calcutta Incident

After the fort fell, these prisoners were confined overnight in a small dungeon within the old Fort William. This came to be known as the Black Hole of Calcutta. Holwell later claimed that the room was overcrowded to the point of suffocation. According to his account, 123 out of 146 prisoners died overnight due to heat, suffocation, and being crushed.

However, the accuracy of Holwell’s claims has been the subject of serious historical debate.

Controversies Surrounding the Black Hole Account

- Doubts over witness reliability: Many historians believe that Holwell’s account was exaggerated, and that he may have inflated the numbers for political reasons.

- Infeasibility of the space: The size of the dungeon was around 267 square feet, which raises doubts about the claim that 146 adult men were confined in it.

- Lack of independent evidence: There is no other contemporary source confirming the incident. Given its alleged magnitude, this absence is seen as suspicious.

- Discrepancies in records: Only 43 individuals were officially listed as missing from Fort William after the fall. Some argue this must reflect the real death toll, although Holwell himself suggested that not all prisoners were official members of the garrison.

Regardless of the exact numbers, Holwell’s narrative was used as a justification for war, and it triggered a strong reaction from the British administration.

British Response to the Fall of Calcutta and the arrival of Robert Clive in Bengal

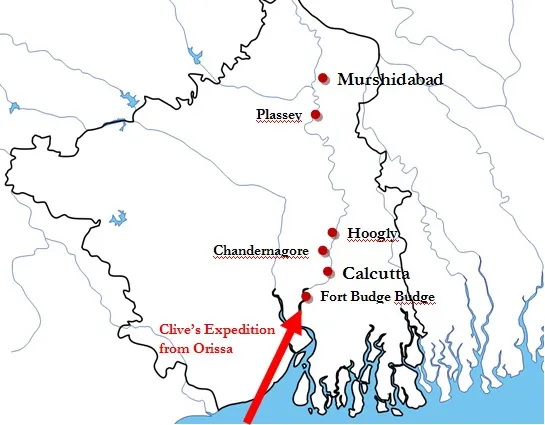

When news of the fall of Calcutta reached Fort St. George in Madras on 16 August 1756, the British Council acted swiftly. An expeditionary force was dispatched to Bengal under the joint command of Colonel Robert Clive (land forces) and Admiral Watson (naval forces).

According to a letter from the Council at Fort St. George, the objective was not only to recover the British settlements but also to secure recognition of the Company’s privileges, demand reparation for losses, and support internal dissatisfaction against the Nawab—without risking a formal war.

Military Preparations and Capture of Calcutta

Clive assumed command of 900 European soldiers and 1,500 sepoys, while Watson led a naval squadron. The fleet entered the Hooghly River in December 1756.

On 29 December, Clive’s forces captured the fort at Budge Budge, and then proceeded towards Calcutta. On 2 January 1757, they attacked and retook Fort William, where the Nawab’s garrison of 500 men surrendered with minimal resistance. The Company was now back in control of Calcutta.

The Council was reinstated, and plans were made for future action. Fort William’s fortifications were further strengthened, and a new defensive line was prepared to the northeast of the city.

Expansion of the Campaign: Attack on Hooghly and Nawab’s Countermove

On 9 January 1757, a contingent of 650 soldiers under Captain Coote and Major Kilpatrick attacked and plundered the town of Hooghly, located 37 km north of Calcutta. In response, Siraj-ud-Daulah raised his army—comprising 40,000 cavalry, 60,000 infantry, and 50 elephants—and marched toward Calcutta, camping beyond the Maratha Ditch.

Though the British had military successes, their trade remained blocked. The Nawab, knowing this, likely intended to prolong the standoff, but made a critical strategic error by choosing to end it with a direct assault.

Clive launched a pre-emptive strike, causing a massive breakdown of the Nawab’s forces. The British suffered 57 casualties, while Siraj’s army lost around 1,300 men. Facing this unexpected defeat, Siraj proposed a negotiated peace.

Treaty of Alinagar (9 February 1757)

The Treaty of Alinagar, signed on 9 February 1757, marked a temporary peace between the Company and Siraj. The treaty was named after “Alinagar”, the new name Siraj had given to Calcutta following its earlier capture.

As per the treaty’s terms:

- The Nawab restored the Company’s factories.

- He recognized the 1717 farman issued by Emperor Farrukhsiyar.

- All British goods were allowed to pass through Bengal duty-free.

- The Company was allowed to fortify Calcutta and mint coins locally.

After the treaty, Siraj withdrew his army to Murshidabad. While peace was restored temporarily, it was not meant to last. Clive had clearly intended from the beginning to settle Company interests permanently in Bengal. Even before his departure from Madras, Clive had written that the expedition would not end with the recapture of Calcutta, but would place British trade and territory on a more secure footing.

Capture of Chandernagar and Renewed Hostilities

With the Seven Years’ War (1756–1763) underway in Europe, the Company feared the increasing influence of the French in Bengal. The French officer Bussy was moving closer to Bengal, and Clive suspected that Siraj might side with them.

Clive planned to capture the French settlement of Chandernagar, located 32 km north of Calcutta. He tried to gauge Siraj’s response but received only vague answers. Treating this as indirect consent, Clive launched an assault on 14 March 1757.

The French expected help from Nawab’s forces stationed at Hooghly. However, the governor of Hooghly, Nand Kumar, had been bribed to stay neutral, effectively isolating the French.

On 24 March, the French showed a flag of truce, marking their defeat. The British rationale for attacking Chandernagar was based on fears that the Nawab’s ties with the French might lead to the revocation of British trading privileges.

The destruction of Chandernagar further strained relations between Siraj and the Company. Siraj was deeply angered by this attack and reignited his hostility toward the British. Facing threats from Ahmad Shah Abdali’s invasion in the north and possible Maratha incursions from the west, Siraj began looking for alliances to strengthen his position against the British.

The Conspiracy and Preparation for Coup

While Siraj had a large army and military advantage, many of his own nobles, generals, bankers, and zamindars had turned against him. The British began forming a secret alliance with disaffected elements in the Nawab’s court.

Key Indian collaborators included:

- Mir Jafar (Siraj’s demoted army chief),

- Jagat Seths (Mahtab Chand and Swarup Chand),

- Rai Durlabh,

- Yar Lutuf Khan,

- Omichund,

- Several powerful officers and merchants.

These groups were upset with Siraj’s attempts to centralize power and his unpredictable behaviour. The Jagat Seths, Bengal’s leading bankers, feared for their wealth and influence under Siraj, which they had enjoyed under Alivardi Khan.

The Company’s representative at Siraj’s court, William Watts, kept Clive informed about these internal divisions. There was also a natural alignment of interests between Indian merchants and the British, as many Indian traders were already supplying goods to the Company and shipping cargo through British-controlled Calcutta instead of declining ports like Hughli.

Thus, a collusion emerged between the mercantile elite of Bengal and Company officials, united in their aim to remove Siraj. Their chosen replacement was Mir Jafar, whose appointment depended on Jagat Seths’ support, which was seen as critical to executing a successful coup.

On 1 May 1757, the plot was presented to the Select Committee in Calcutta, which formally approved it. A secret treaty was drafted between the Company and Mir Jafar. The agreement stated that in exchange for supporting the British militarily, Mir Jafar would be installed as the Nawab, and the Company would be compensated financially for the attack on Calcutta.

Whether this conspiracy originated internally within the Murshidabad court and was later exploited by the British, or was actively created by them, is a matter of historical debate. But what is undisputed is that a deliberate and organized conspiracy involving the Company, Indian bankers, generals, and court factions led to the final overthrow of Siraj-ud-Daulah.

This set the stage for the Battle of Plassey, fought in June 1757, where Siraj was defeated, bringing an end to Bengal’s independence and laying the foundations for British political control in India.

The Battle of Plassey (23 June 1757)

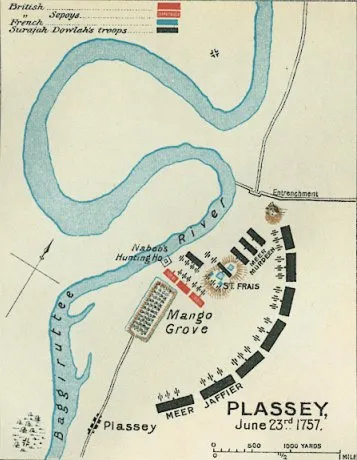

The Battle of Plassey, fought on 23 June 1757, was a decisive military engagement between the forces of Siraj-ud-Daulah, the Nawab of Bengal, and the British East India Company, commanded by Robert Clive. Though described as a battle, it was, in reality, hardly more than a skirmish, as the outcome had already been pre-arranged through a secret conspiracy involving key elements of the Nawab’s own camp.

The battle marked a turning point in Indian history, leading to the establishment of British rule in Bengal—a foundation that would soon extend to the entire subcontinent and last for over a century.

Strategic Importance and Location

The battle was fought at Plassey (Palashi), located on the banks of the Bhagirathi River, approximately 150 km north of Calcutta and just south of Murshidabad, the capital of Bengal. This location was strategically significant, close to the river and a central route between key British and Nawabi positions.

The arrival of Robert Clive from Madras with a strong force had already boosted British confidence. Meanwhile, the British had succeeded in building a secret alliance with Mir Jafar (the commander of Siraj’s army), Rai Durlabh, Jagat Seth (the powerful banker), and Omichand.

As per the conspiracy, Mir Jafar was promised the Nawabship of Bengal in exchange for his betrayal of Siraj and military cooperation with the British. The plot was carefully laid, and the victory was almost assured before the first shot was fired.

Advance to Plassey and Internal Delays

On 14 June, Clive officially sent a declaration of war to Siraj. In reaction, Siraj, suspecting Mir Jafar’s intentions, ordered an attack on Mir Jafar’s palace. However, he also sought and received a false assurance from Mir Jafar that he would not side with the British during the battle.

Siraj issued orders for his full army to march toward Plassey, but a delay occurred because his troops refused to move until their unpaid wages were cleared. As a result, his forces only reached Plassey by 21 June, just two days before the battle.

Composition of Forces and the Role of Conspirators

The disparity in numbers was stark:

- Siraj-ud-Daulah’s army consisted of 50,000 infantry, 28,000 cavalry, and 50 war elephants, with some support from the French.

- Clive’s force included just 3,000 men, of whom only a few hundred were British soldiers, and the rest were Indian sepoys.

The largest division of Siraj’s army, commanded by Mir Jafar, remained idle during the battle. Similarly, the forces of Rai Durlabh and Yar Lutuf Khan also did not engage in combat, despite being present near the battlefield.

Only two commanders—Mir Madan and Mohan Lal—actively fought for Siraj. Both led their contingents with determination. Mir Madan, known for his bravery, fought valiantly but was eventually killed on the battlefield. His death shattered the morale of the Nawab’s camp.

Following Mir Madan’s death, Siraj was advised by Mir Jafar to halt the battle and recall Mohan Lal. Despite some resistance, the Nawab eventually lost confidence in his command and fled the battlefield on a fast camel, further demoralizing his troops who then began to disperse and retreat.

Collapse of Nawab’s Army and Aftermath

As predicted by his astrologer—possibly bribed by conspirators—the Nawab was warned of defeat. With his army disoriented and leaderless, no organised resistance remained. Siraj’s flight from the battlefield ended any hope of regrouping. He was later captured and killed by Miran, the son of Mir Jafar.

Following Siraj’s death, Mir Jafar was installed as the new Nawab of Bengal and entered Murshidabad in triumph. The British East India Company had now placed its own political ally at the helm of Bengal’s administration, effectively bringing the region under indirect Company control.

Aftermath of the Battle of Plassey

Treaty with Mir Jafar and Territorial Gains

Following the defeat of Siraj-ud-Daulah at the Battle of Plassey, the British East India Company formalized a treaty with Mir Jafar, elevating him to the position of Nawab. As per the agreement:

- The Company acquired all land within the Maratha Ditch and an additional 600 yards beyond it.

- The Zamindari of the 24 Parganas was handed over to the Company.

- The firman of 1717 issued by Mughal Emperor Farrukhsiyar was reaffirmed, ensuring the Company’s right to duty-free trade.

The treaty also required restitution of losses suffered by the British during the Calcutta campaign. This included massive financial donations to the navy squadron, the army, and the governing committee, totalling ₹22 million. However, it soon became clear that Siraj’s treasury was overestimated. On 29 June, a council meeting with the Seths and Rai Durlabh decided that half the amount would be paid immediately — two-thirds in cash, and one-third in jewels and valuables.

A dramatic moment followed when Omichand, who had played a role in the secret treaty, learned that he would receive nothing. The shock reportedly drove him insane, marking a tragic end to one of the conspirators’ stories.

Clive’s Return to England and Recognition

In 1760, Robert Clive returned to England, hailed as a national hero. His success at Plassey and political manoeuvring earned him immense fame. He was honoured by the British Government with the title Lord Clive, celebrated as the “Victor of Plassey” and founder of British power in India.

However, it is important to note that at this point, the British did not hold complete control over Bengal. Nor was it their initial intention to do so. Their primary goal remained enhanced commercial privileges, not territorial rule.

Though the British orchestrated the political shift, Mir Jafar remained the Nawab, still commanding the largest army in Bengal. Clive himself wrote, “So large a sovereignty may possibly be an object too extensive for a mercantile company,” expressing doubts about the practicality of direct rule.

Political and Strategic Significance

The Battle of Plassey is considered one of the most consequential events in Indian history. Though militarily minor, the battle had enormous political ramifications:

- It marked the beginning of British political supremacy in India.

- It ended the influence of the French, their primary European rivals in Bengal.

- The Company secured grants of territory to maintain a full-fledged army, thereby enhancing its military capacity.

- It placed Bengal’s resources at the disposal of the Company, providing a launchpad for future conquests in the Deccan and North India.

Historians often remark that the English won not through military brilliance but through political manipulation. As many have described it: “a transaction in which the bankers of Bengal and Mir Jafar sold out the Nawab to the English.”

Mir Jafar: A Puppet Nawab

Mir Jafar (1757–1760), installed as Nawab, remained entirely dependent on the British. Lacking administrative skill and political strength, he relied on the Company for his position and protection against external threats.

- A British force of 6,000 soldiers was permanently stationed in Bengal to support him.

- The sovereignty of the British over Calcutta was formally recognised.

- An English Resident was posted at the Nawab’s court, marking the start of institutionalised political control by the Company.

Plassey Plunder: Loot, Trade, and Economic Shift

What followed the battle has often been termed the “Plassey Plunder”. The Company and its officials gained unprecedented access to Bengal’s resources:

- The British monopolised Bengal’s trade and commerce.

- Bengal, then India’s most prosperous province, was looted of its wealth.

- The funds extracted from Bengal allowed the Company to expand militarily across the subcontinent, including in the Deccan and North India.

The French influence collapsed completely:

- In 1759, the British defeated a larger French garrison at Masulipatam, gaining control of the Northern Circars.

- The Dutch were also defeated, eliminating any remaining European competition in eastern India.

Between 1757 and 1760, the Company received ₹22.5 million from Mir Jafar. Clive alone received a personal jagir worth £34,567 in 1759. The army and navy were awarded £275,000 each, to be distributed among officers and soldiers.

Shift in British Economic Structure

Prior to 1757, British trade in Bengal was financed through bullion imports from England. After Plassey:

- Bullion import ceased.

- Bengal’s revenue was exported to China and other parts of Asia.

- This gave the British a competitive advantage over their European rivals.

Taxes imposed earlier by the Nawabs disappeared. The Company’s servants now freely abused dastaks (free trade passes) for private trade. This gave them enormous personal profit, at the cost of Bengal’s economy.

It is argued by many that the wealth plundered from Bengal helped finance the early Industrial Revolution in Britain, which began shortly after—around 1770.

Impact on Bengal and Rise of Colonialism

While the Company gained power and riches, the people of Bengal suffered immensely:

- Lawlessness increased, and economic exploitation by Company servants intensified.

- Local industries and artisans faced ruin.

- Wealth was drained, and the region’s prosperity collapsed within a generation.

The British built an army of Indian sepoys, which they used to expand their colonial control over other parts of the Indian subcontinent. To safeguard India’s wealth, they also acquired buffer colonies across Asia, including Singapore, Penang, Burma, Nepal, and Malacca.

British dominance was also aided by their modern artillery, superior navy, and military discipline. These technological advantages allowed them to maintain control over vast territories with relatively small forces.

Conclusion: End of One Epoch, Beginning of Another

The Battle of Plassey did not just change the fate of Bengal; it altered the course of Indian history. It was:

- A political turning point, giving the British control of Bengal.

- A strategic victory over the French and Dutch.

- A commercial revolution, turning the British from merchants into rulers.

It has therefore rightly been said that Plassey marked the end of one epoch and the beginning of another—an epoch of indigenous sovereignty giving way to colonial domination.